Here’s an extremely thought-provoking guest post by Megan Evans, Research Assistant at the University of Queensland in Kerrie Wilson‘s lab. Megan did her Honours degree with Hugh Possingham and Kerrie, and has already published heaps from that and other work. I met Megan first in 2009 and have been extremely impressed with her insights, broad range of interests and knowledge, and her finely honed grasp of social media in science. Smarter than your average PhD student, without a doubt (and she has even done one yet). Take it away, Megan.

—

Resolving the ‘Environmentalist’s Paradox’, and the role of ecologists in advancing economic thinking

Aldo Leopold famously described the curse of an ecological education as “to be the doctor who sees the marks of death in a community that believes itself well and does not want to be told otherwise”. Ecologists do have a tendency for making dire warnings for the future, but for anyone concerned about the myriad of problems currently facing the Earth – climate change, an ongoing wave of species extinctions and impending peak oil, phosphate, water , (everything?) crises – the continued ignorance or ridicule of such warnings can be a frustrating experience. Environmental degradation and ecological overshoot isn’t just about losing cute plants and animals, given the widespread acceptance that long-term human well-being ultimately rests on the ability for the Earth to supply us with ecosystem services.

In light of this doom and gloom, things were shaken up a bit late last year when an article1 published in Bioscience pointed out that in spite of declines in the majority of ecosystem services considered essential to human well-being by The Millenium Ecosystem Assessment (MA), aggregate human well-being (as measured by the Human Development Index) has risen continuously over the last 50 years. Ciara Raudsepp-Hearne and the co-authors of the study suggested that these conflicting trends presented an ‘environmentalist’s paradox’ of sorts – do we really depend on nature to the extent that ecologists have led everyone to believe?

The article has generated quite a bit of attention, as it challenged one of our most fundamental perceptions of our relationship to the natural environment. If it were possible for humans to supersede nature, then our current march through the Anthropocene and into a four or six degree-hotter world shouldn’t be of much concern for us (biodiversity might not be so lucky). Raudsepp-Hearne and colleagues tested four main hypotheses to try to explain this finding: that well-being is not measured correctly, provisioning services such as food production, which are increasing, are more important for well-being than other services, technology has decoupled humans from our relationship with nature, and the prospect of a time lag in humanity’s response to diminishing ecosystem services.

The article has been discussed in more detail in a more recent issue of BioScience, where Anantha Duraippah pointed out (and as hinted at by Tim Beardsley in the original editorial) that aggregating estimates of human well-being at the global scale can mask declines and inequalities across sub-global and country-level scales. Duraippah also questioned the reliability of the Human Development Index (HDI) as an indicator of human well-being, and pointed towards findings of the recent Stiglitz Report on the Measurements of Social and Economic Progress, commissioned by French President Nicolas Sarkozy. The report identified numerous factors that make up well-being: those that can be measured objectively including employment and income, and subjective measures such as emotional happiness. Both types of measures – objective and subjective – were regarded as critical to obtain a well-rounded view of society’s genuine progress and well-being.

The response by Gerard Nelson argued that better technology, data and economic accounting will help to resolve the paradox, while most commentators across the blogosphere (see here, here, and here) focussed mainly on the final hypothesis proposed by Raudsepp-Hearne to explain the paradox – the expectation of a time lag in humanity’s response to diminishing ecosystem services. Technology (or more likely, cheap fossil fuels) and social innovation might be contributing to this time lag, and perhaps delaying the onset of a tipping point in ecosystem function and subsequently human well-being.

Interestingly, there have also been some comments (here and here) directed from an alternative perspective – that humans simply don’t rely on natural resources to the extent that environmentalists purport, and the continued positive trend in HDI in the face of environmental degradation is confirmation of this assertion. The environmentalist’s paradox is not a paradox because global growth in human capital (such as knowledge and individual skills) is substituting for our reliance on natural capital – ultimately meaning that human well-being will continually improve without restriction.

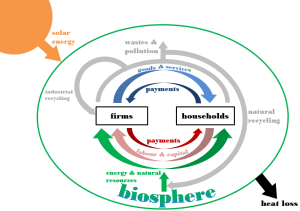

Fig. 1. Neoclassical (mainstream) economic view of the economy (http://goo.gl/F3ZSA). © http://www.irconomics.com

To understand this argument better, it is worth looking at the issue from first principles – beginning with the circular flow model of mainstream economic theory (Fig. 1). Here all economic activity is considered to be contained within a whole, self-contained system, where the environment is a subsystem of the greater economy. Resources produced by the environment (i.e., natural capital) are converted to human capital during the economic process, but environmental degradation associated with this conversion is not necessarily a problem since human-made capital could effectively substitute for the loss of natural capital. Increased efficiency in the conversion of natural to human capital, coupled with technological advancements, mean that according to this viewpoint the economy can increase in scale without any limits, and as such human well-being can continue to increase indefinitely.

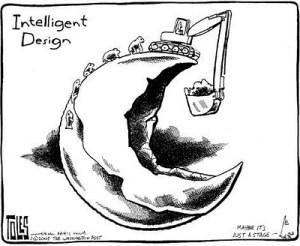

The main problem with the circular flow model is that it is effectively a perpetual motion machine – a model that violates basic physical laws such as entropy and the conservation of mass and energy. Viewing the economy as a whole, isolated system that generates no wastes and requires no additional inputs is like describing an animal in terms of its circulatory system, but ignoring its digestive tract2. If the circular flow model of the economy system is to satisfy the laws of thermodynamics, the system cannot be a ‘whole’, but instead sits within a larger system, the Earth, which is bounded by biophysical limits (Fig. 2). These limits mean that there are indeed limits to scale of the human economy relative to the natural economy, and that aggregate human well-being is ultimately constrained by these limits.

Fig. 2. Ecological economic view of the economy (http://goo.gl/F3ZSA)

So we have two alternative viewpoints – one which stresses the importance of the environment for human well-being, and another which argues that the environment perhaps isn’t so important after all. The conclusion reached by Raudsepp-Hearne and her colleagues argue that to resolve the paradox, ecologists need to direct efforts into understanding the links between ecosystem services and multiple aspects of human well-being, trade-offs and synergies between services, the role of technology and better forecasting of changes and potential tipping points in the future supply of ecosystem services. That being said, I can’t help but feel that the discovery of ecological tipping points – especially at the global scale – might not be something to cheer about while the Earth remains on its unsustainable trajectory with no ‘Plan B’ in sight.

It’s hard to disagree with the importance of this research direction, but perhaps the most interesting outcome of Raudsepp-Hearne’s article is that the subsequent discussion has shown how polar opposite conclusions can be drawn as to why and how the environmentalist’s paradox will eventually be resolved, depending on your pre-existing view on humanity’s relationship to the environment. It might be tempting just to disregard the viewpoint which considers the maintenance of the environment as unnecessary for human well-being, but as John Gowdy and colleagues argued in a recent essay3, it’s worth remembering that mainstream economics perceives the world as in Figure 1, where physics doesn’t exist and the environment is often considered as ‘external’ to the economic system. This means that the vast majority of economic decision making is driven by an unrealistic view of the world, which has obvious consequences for biodiversity conservation.

Given these stark differences in the preanalytic visions of mainstream economists and ecologists (Fig. 1 and Fig. 2m respectively), it seems that working to resolve the environmentalist’s paradox is only the first step, and that a more systemic perspective is needed to understand how the world is to move onto a sustainable pathway. Raudsepp-Hearne and her colleagues suggest that cross-disciplinary discussion is needed to create a “…science of sustainability capable of integrating the complexities of culture, human well-being, agriculture, technology, and ecology”. But such a discussion also needs to include a critical analysis of many of the theories which underpin modern economics to become compatible with broader goals for biodiversity conservation and long term sustainability.

Ecologists and conservation scientists in particular have a hugely important role to play in advancing economic thinking – but as Gowdy points out, it can be difficult for ecologists ask the fundamental questions required because of the differences in language used between disciplines. Paul Ehrlich has argued that ecologists should become economists, and vice versa – but while a change in profession might not always be possible, there is still an urgent need for much bigger and louder conversation between ecologists and economists if we are to truly build a science of sustainability.

There are, of course, many examples of ecologists and economists working together – for example, the annual The Askö Meetings which have built a shared understanding by leaders in both fields. Realistically though, these conversations shouldn’t be taking place just once a year in a remote island off the coast of Sweden (although it does sound lovely), but in conferences, within and between university and government departments, in tea rooms, lecture theatres and everywhere that ecologists and economists could potentially cohabitate. Of course interdisciplinary work doesn’t just happen if you throw people into a room together, so what else could be done? A buddy system? Or a trip to the pub? I don’t know what the answer is, but whatever happens, this is a conversation that needs to happen sooner rather than later. Now is the time to be part of the development of a ‘Plan B’.

—

1Raudsepp-Hearne, C., G. D. Peterson, et al. (2010). Untangling the Environmentalist’s Paradox: why is human well-being increasing as ecosystem services degrade? BioScience 60: 576-589. doi:10.1525/bio.2010.60.8.4

2Daly, H. E. and F. Farley (2010). Chapter 2: The Fundamental Vision. Ecological Economics: Principles and Applications, 2nd Edition. Island Press, Washington, DC.

3Gowdy, J., C. Hall, et al. (2010). What every conservation biologist should know about economic theory. Conservation Biology 24: 1440-1447. doi:10.1111/j.1523-1739.2010.01563.x

[…] the Environmentalist’s Paradox”. ConservationBytes.com. April […]

LikeLike

[…] essay had a big influence on my understanding of economics, and spurred me to string together some semi-coherent thoughts on the topic earlier this year. Gowdy argues that the mainstream model of economic thought is essentially […]

LikeLike

[…] essay had a big influence on my understanding of economics, and spurred me to string together some semi-coherent thoughts on the topic earlier this year. Gowdy argues that the mainstream model of economic thought, which he terms […]

LikeLike

[…] the Environmentalist’s Paradox”. ConservationBytes.com. April […]

LikeLike

[…] https://conservationbytes.com/2011/04/07/environmentalist%E2%80%99s-paradox/ LikeBe the first to like this post. […]

LikeLike

[…] 9 06 2011 Here’s another great guest post by Megan Evans of UQ – her previous post on resolving the environmentalist’s paradox was a real hit, so I hope you enjoy this one […]

LikeLike

Useful as it is when arguing with mainstream economists that ecosystems have practical value, I’d like to suggest that the use of the term “ecosystem services” itself perpetuates a mindset of nature solely existing to serve humans and human activities.

So long as we continue to implicitly or explicitly frame our analyses and attempted solutions with that assumption we will never get past a futile tug-of-war with those on the other side of the dialectic.

I’d offer that Einstein’s statement – that problems can only be solved at a higher level of awareness than where they were created – applies here.

For anyone interested in a thought piece around this notion, please see UN University’s OurWorld 2.0 web magazine article, “To Serve the Ecosystems that Serve Us” (http://ourworld.unu.edu/en/satoyama-offers-ecosystem-gifts-rather-than-services/)

LikeLike

It seems to me that our quality of life in developed countries is at the expense of future generations and less developed countries, as well as biodiversity. It depends on using mineral and energy resources rather than leaving them for future generations as if people living now matter and those to follow in hundreds and thousands of years don’t matter. If we can’t maintain a standard of life without depending on massive exploitation of resources, nature and disadvantaged people, future generations have no hope. Quality of life also depends on living with a conscience.

LikeLike

Thanks.

However, the differences between Figures 1 and 2 have been discussed for decades already.

As I see it, human societies have always operated in an open system, but they have also always attempted expand the human realm of it. This happens at the cost of the biosphere part (as Earth is limited), by substituting natural functions of the system with non-natural functions that are more efficient from the human perspective as service providers. Simple technological advancements have allowed this kind of expansion in the past, such as cultivation, and later, e.g. water purification plants. The important point is that it does not stop here: the advancement of technology and biotechnology will make it possible to expand the human realm even further.

I think we are too optimistic if we think we can save nature by making our current economic dependencies to biodiversity visible in economic models. The concept of ecosystem services is a useful way to demonstrate the current benefits of preserving biodiversity to governments, but many of these benefits will prove to be real only in a limited time scale: in the future, technological advancement and the scarcity of natural resources may make it more cost-efficient to replace natural “service providers” with more efficient, bio-engineered ones.

In the long term, I think we will need to conserve wild nature because of its intrinsic value, because of its beauty, and because of the pleasure and adventure it provides us with. Because it is NOT created by us. These “services” are quite unique, but they are extremely difficult to put a price tag on. If we wish to try, we need new kinds of studies on how nature affects our psyche and well-being.

And what comes economists, they need to figure out how to provide growth without expanding the human realm in this open system.

LikeLike

I’ll acknowledge that the differences between Fig1 and Fig2 have been discussed for a long time, but that shouldn’t mean the issue is unimportant or not worth examining further. The main point I tried to communicate in the article is the need to engage much more strongly in this discussion – and in close collaboration with economists, psychologists other social scientists. I agree that technological advancement is important, but I think it would be too optimistic for us to expect technology to effectively substitute for nature. I feel that arguing for the need to conserve nature based predominantly on intrinsic value (see Maguire and Justus 2008 and Colyvan et al 2010) and leaving economists alone to figure out how to grow the economy without breaching biophysical limits (if they agree those limits exist) is unlikely to be successful for biodiversity conservation in the long run.

LikeLike

Excellent article and I fear that the technological-human capital-camp will win the day,despite the recent events in Japan. Many younger people,here in the UK for example, are growing up in an increasingly uniform and depleted world: they have no real awareness of the number of species which are disappearing,since the process began before they were born. They also have access to an increasing array of technological advances and are less responsive too the natural world than previous generations. Attempts to promote awareness of the dangers posed by human population and economic growth are being stone-walled by complacency and political inertia. Nevertheless, CASSE has just won a well-deserved award, so hope remains.

LikeLike

It’s a good point Laura – hard to answer though. Herman Daly has said on this point that ‘the difference between these two visions could not be more fundamental, more elementary, or more irreconcilable.’

But this is a pretty bleak picture, considering what’s at stake. This article describes a process of collaboration between ecologists and economics that helped both parties forged a common understanding – I think the key is communication. Focusing on the ‘irreconcilable differences’ is not going to help. The other thing is education – why is it normal practice to do an economics degree without some basics ecology and physics, and for ecology students to skip economics (and maths for that matter?).

LikeLike

Do you think the paradox can be really solved when there are people perceiving the world in fundamentally different ways? is like trying to convince someone that apples taste better than pears.

LikeLike