Another soul-searching post from Alejandro Frid.

—

Confession time. This is going to be delicate, and might even ruffle some big feathers. Still, all of us need to talk about it. In fact, I want to trigger a wide conversation on the flaws and merits of what I did.

Back in March of this year I saw a posting for a job with the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute (SCBI) seeking a ‘conservation biologist to provide expert advice in the design and implementation of a Biodiversity Monitoring and Assessment Program (BMAP) in northern British Columbia, Canada’. The job sounded cool and important. I was suited for it, knew northern British Columbia well, and loved the idea of working there.

But there was a catch. The job was focused on the local impacts of fossil fuel infrastructure while dissociating itself from the climate impacts of burning that fuel, and involved collaborating with the fossil fuel company. According to the posting, this was not a new thing for the Smithsonian:

Guided by the principles of the Convention on Biological Diversity, SCBI works with a selected group of oil and gas companies since 1996 to develop models designed to achieve conservation and sustainable development objectives while also protecting and conserving biodiversity, and maintaining vital ecosystem services that benefit both humans and wildlife.

Given that climate change already is diminishing global biodiversity and hampering the ecosystem services on which we all depend, the logic seemed inconsistent to me. But there was little time to ponder it. The application deadline had just passed and my soft-money position with the Vancouver Aquarium Marine Science Centre was fizzling out. So I applied, hastily, figuring that I would deal with the issue later, if they ever got back to me.

Months went by without a word and I felt relieved, freed from choice. But all that changed with an email requesting a video interview as soon as possible. Using the legitimate excuse that I was out in an intense field course, I managed to stall the interview by a week, which gave me some time to consult friends, do some reading and CO2 calculations, and just wrap my mind and conscience around the whole thing. All this led to my letter to the Smithsonian, reproduced below in its entirety, sent the day before my scheduled interview.

–

7 May 2013

To Whom It May Concern:

I was pleased to find out last week that the Center for Conservation Education and Sustainability (CCES) of the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute (SCBI) shortlisted me for an interview regarding the position of conservation biologist in northern BC. I have great regard for SCBI, and at first I was delighted by the potential opportunities. In the last few days, however, I have reviewed the context of the position and have decided to withdraw my application. My reasons for doing so are based entirely on personal ethics. Let me explain.

According to the job description, the work would entail “research to study, understand, predict, and monitor the impact of infrastructure development projects on biodiversity and ecosystem services”. In this case the infrastructure, to be built by Apache Canada Ltd., is to serve the export of liquefied natural gas (LNG) and includes a plant, storage facility, marine-on loading facilities, and the 470 km Pacific Trails Pipeline. On the positive side, it is good that the very high scientific standards of SCBI will help reduce the local impacts of the LNG infrastructure project. On the negative side, a sole focus on local impacts implicitly turns a blind eye to the severe climate impacts associated with the project.

According to their website, The Pacific Trails Pipeline will have a capacity of up to 1 billion cubic feet per day. When burnt, that amount of gas would release 19 Mt of CO2 per year [1]. Emissions generated during extraction, transport, processing, storing, and handling would be additional.

The impact on biodiversity and ecosystem services of releasing that much CO2 into the atmosphere would, in my opinion, trump the accomplishments of any project focused on local impacts of infrastructure. For instance, Rogelj et al. (Nature Climate Change 2013, 3:405-412) estimate that to avoid the climate disasters that will occur if global temperatures rise more than 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial times, annual carbon emissions must drop globally from 52 Gt emitted in 2012 to 41-47 Gt by 2020. Given that the Pacific Trails Pipeline would transport annually the equivalent of 0.04% of total global emissions generated in 2012, the development of that project or any other new fossil fuel infrastructure is the opposite of what should happen if we are to reduce the impacts of anthropogenic climate change on biodiversity and society.

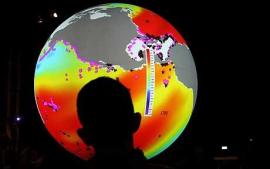

I want to conclude by saying that I have great admiration and respect for SCBI. Having said that, I am stunned that SCBI is not taking a stronger stance against the climate and global impacts associated with new infrastructure for fossil fuel exports. While all sorts of arguments for socioeconomic and political compromises can be made, in the end it comes down to physics and chemistry, which know no compromise. The current concentration of atmospheric CO2 is 398 ppm and rising at an average rate of 2 ppm/year. While LNG is a less dirty fuel than bitumen or coal, it is still a fossil fuel that only contributes to the rise in CO2 emissions, taking us farther away from 350 ppm, the upper limit of ‘safe’ CO2 concentrations [2]. Emissions have to go down, and building new infrastructure for fossil fuels is not going to make that happen.

So please accept the withdrawal of my application.

Respectfully,

Alejandro Frid, PhD

–

A day after sending my letter, journalist Stephen Leahy reported that

Two weeks later, Carbon Tracker and the Grantham Research Institute released their Unburnable Carbon report, which points to the economic foolishness of building new infrastructure for fossil fuels that would lock us deeper into a carbon economy. And the more I read the more I find peer-reviewed evidence that fossil fuel corporations have been key players of the climate change denial industry, and that barriers to large-scale use of renewable energies are ‘primarily social and political, not technological or economic‘. So I only stand firmer on my decision today.

I had sent my letter with no expectation of a substantive response. Accordingly, the reply was limited to ‘we appreciate your thoughts’ and ‘best of luck in your future endeavours’. Fair enough. The Smithsonian had signed on to a job interview for work that they had already committed to, not to an ethics debate. So it is up to the rest of us—and the Smithsonian is welcome to join anytime—to discuss this matter further.

What would you do in a similar situation?

Is the long-term conservation of biodiversity and ecosystem services best served by working with the fossil fuel industry on local impacts or by boycotting industry collaborations that implicitly legitimise and endorse further growth of our carbon economy?

Should professional societies, like the Society for Conservation Biology, develop a formal position on these matters?

Over to you.

Alejandro Frid alejfrid@gmail.com[2] Hansen, J., Mki. Sato, P. Kharecha, D. Beerling, R. Berner, V. Masson-Delmotte, M. Pagani, M. Raymo, D.L. Royer, and J.C. Zachos, 2008:Target atmospheric CO2: Where should humanity aim? Open Atmos Sci J, 2, 217-231, doi:10.2174/1874282300802010217

[…] to his young daughter‘. See Alejandro’s previous posts on ConservationBytes.com here, here, here, here, here and […]

LikeLike

It is great to see so many passionate and thoughtful responses to my post. My original intention was to not reply at all. But comments have yet to stop, so I could not resist stepping back in.

Rather than replying to specifics, I will ask readers to consider the distinction between a project that creates new infrastructure for fossil fuel development vs. one that merely logs, fishes or builds dams. Yes, I used ‘merely’ with full intention because of the differences in temporal and spatial scale of impact.

New infrastructure for fossil fuels is expensive and the associated profits are extraordinary. Once investors have footed the bill, society commits to burning those fuels for multiple decades. Try telling investors that their new multi-billion pipeline has to run dry ahead of schedule to save the climate and—even if you are a head of state—you will hear from their powerful lawyers. So a shift towards a low carbon economy is unlikely to even begin without a moratorium on new infrastructure for fossil fuels. Under current emission scenarios, which are unlikely to change without that moratorium, we are heading towards a 6 to 8 degree increase in temperature by 2100. That means that most local biodiversity that we were proud to conserve in 2013 will be on pretty tenuous ground long before 2100. Ever tried to de-acidify an ocean?

In contrast, a logging, industrial fishing or hydro project is a whole different beast that I am quite willing to engage in industry collaborations. For instance, I have worked with a resource extraction company in an effort to reduce its impact on mountain ungulates. Given a stable climate, or at least one that has not gone berserk in response to our carbon economy, logging, fishing and similar industries can be managed according to Ecosystem Based Management principles intended to foster resilience at a scale of decades (assuming political will backs the scientific recommendations). I can work with that. But I am still steering clear from industries that are blowing the entire planet out of the Holocene and whose impacts will range from centuries to millennium.

If anyone wants to collaborate on writing something more formal for a journal or think about a symposium of sorts, I suppose that we should talk.

Keep those comments coming. And thanks for all the fish.

Alejandro

LikeLike

Great discussion here: I would say – why not take the job and cause change / impact from within? They obviously saw something in you – and were willing to accept you. If we always decline to work with “industry” – then we are deliberately excluding ourselves from a process of improvement – from learning, and from providing our scientific knowledge to those systems that REALLY need our input. This is akin to refusing to work with the World Bank because they fund development projects – that of course destroy biodiversity. But brave people who took that chance early on – have now created one of the world’s greatest funds for env / biodiversity work. Without people willing to jump in and initiate change, the Bank would never have learned. I’m not sure the climate change card was wisely used here. Alejandro, I do understand your reason for declining the position, but – how is it that we (environmentalists / conservationists) can drive cars, fly on planes, and take a bus to go shopping – but we can’t “ethically” work in a professional setting with the very groups that we are already contributing to on a daily basis? As it was said above – the potential for someone not as passionate about forcing this climate change issue as part of the work – might now be in line for the job. You just let a possibly less qualified person manage this. There is always a time for every institution to make difficult decisions – and you could have had a great impact by making this group / job suit your philosophy and learning from you. If you only decide to work in a place that does not need such change – what is the point? It’s like taking the easy class in school because you know you’ll get an A. ? I see this in California all the time – we need the brave!! Otherwise… let’s not work with politicians, because they are all corrupt. Let’s not work with the fishing industry because they are abusing our oceans. Let’s not work with car manufacturers, because they’ll never go green. Let’s not work with hunters, farmers, cattle industry,…. or oil companies …. Let’s just label them the bad guys and refuse to get involved – because that will make the world a better place!?

Take the chance!! – go back there and tell them you are indeed ready for this – you ARE the right candidate. I wish I had your credentials, I would jump on it in a second.

B Kosravi

LikeLike

I believe this is one of the most interesting and important philosophical discussions we can have and agree whole heartedly with David Jay, we need diversity of opinion and action on this matter. If everyone took the job, there would be no purists sitting on the moral high ground; if no one takes the job, there will be no regulation from the ‘inside’. Lets encourage informed responsible scientists to engage on this topic no matter where they sit philosophically because in the end, there is more in common on this thread than not.

LikeLike

Hi Alejandro,

Thanks for sharing this experience with the wider conservation community, and for recognising that this is an important ethical issue that deserves consideration and debate.

I think the first thing to say is that you did a good thing. You made an ethical judgement and you took a stand. The world needs people who do that, so well done.

However, I think the world also needs people who can compromise their ethical position (without abandoning it!) in order to engage in some way with their ‘ideological opponents’. Unfortunately I don’t think any number of conservation biologists ‘taking a stand’ is going to hold the fossil fuel industry to ransom. It is noble and it is good, but it is probably not the path to radical change.

Change requires some people (but not all, I think) to work within the system, to have a dialogue with the fossil fuel industry and make the case for change as strongly as they can to the people who are in a position to act on it. Obviously these people will have to spend a lot of time biting their tongues, and probably quite a bit of timing being criticised by people whose principles they share, but whose strategy is different. I have never done it, but I expect it is a hard and weary path to tread.

But I think that the ‘environmental movement’ needs that spectrum of people, from those who are in so deep they hardly seem like environmentalists at all, through those who make some compromises in order to push some points harder, to those who take a stand and keep their principles intact. I believe that everyone on this spectrum needs to have the others to debate with and to evaluate themselves against, so that they can understand what their position is and what is or is not right for them. Consequently the movement itself ranges from radical protesters to public officials and everything in between, and I think that is a good thing.

Your personal experience brings this into sharp relief, which is a good thing, but I think many conservationists are faced with similar dilemmas all the time, and I wonder how widely this is acknowledged. Many government projects are predicated on policies that some conservationists would not fully endorse, a lot of conservation funding comes directly or indirectly from corporate (or other) sources that are not entirely consistent with the goals, many certification or regulation schemes are uneasy alliances of those who want to make minimal changes and those who are prepared to shelve their more radical suggestions in order to stay at the table. I think many choices made by conservationists involve weighing up practical advantages against ethical ideals, and the more this is talked about, hopefully the easier and better those choices will become for everyone.

So, I think your dilemma is far from unique. However, your decision to present and debate it so clearly is much more notable, and highly laudable for it.

LikeLike

“…the ‘environmental movement’ needs that spectrum of people, from those who are in so deep they hardly seem like environmentalists at all, through those who make some compromises in order to push some points harder, to those who take a stand and keep their principles intact.”

The problem with this idyllic scenario is that environmentalists in deep with the eco-destroyers have all kinds of opportunities to formalise the compromises they are willing to make, and all kinds of personal rewards for doing so. Meanwhile those that take a committed stand are likely to find themselves on the margins with no access to formal policy making and little more than their principles to sustain them.

Here in Tasmania our ‘peak’ environment groups have actively engaged with, and promoted, human rights and nature abusing logging corporations, while deliberately undermining conservationists who take a more principled and opposing stance. The farce culminated with the leader of a prominent Australian environment organisation on stage in Tokyo singing the praises of green-washed timber products from unsustainably managed high conservation value forests.

In Tasmania, and I suspect elsewhere, the ‘spectrum of people’ that make up the environment movement has been revealled to be a hierarchy that favours those who self-select to fundamentally compromise their values. Sadly, they do hardly seem like environmentalists at all.

I think Alejandro’s decision was commendable, and especially so because he took the opportunity to raise his ethical concerns with the employer.

When the alternative is paid compliance, conscientiously objecting as noisily as possible seems like a good choice.

LikeLike

I’m not a professional biologist, but I am deeply concerned about our future and how, as a society, we so often fail to connect the dots between the urgent need to reduce emissions to avoid runaway climate change and the fossil fuel development projects that threaten to take us over the cliff.

I don’t think there is an “ideal candidate” for a position that abets putting more carbon in our atmosphere. As Bill McKibben has said, this kind of work amounts to “gilding the Lily.” No rational person should want these fossil fuels to be safely exported and burned.

What if, instead of doing work that hastens our end, everyone involved just downed their tools and refused to take part? This is what Alejandro has effectively done, and I hope others follow his lead. Our survival demands no less.

LikeLike

These comments by KW are right on the mark. AF made a courageous decision and I applaud his action.

LikeLike

For me Alejandro’s blog reflects an ongoing issue amongst biology professionals for a long time (most in BC are involved in natural resource management in one way or another): “do we or don’t we, and if I don’t do it, someone with less moral and ethical fortitude might do it…”

I think I remember the posting Alejandro references as well. I may have even considered it – what conservation biologist in their right mind wouldn’t want to work for the Smithsonian and stay in BC to boot! Until I saw what it entailed. I made the decision a long time ago about where I was willing to take myself professionally. So while I have a number of colleagues who do work on mining, oil and gas issues (good biologists who I respect for their choices and expertise and voices) I could never do it. I won’t even take offers to do riparian assessments that the province requires because I believe the science is seriously skewed and flawed. So I pick away grant by grant to work with the organizations and focus areas that I feel align well for me. Or through influencing my profession in the ways I can. I live with the lower income that is the trade-off. It is not an ideal life without stressors to be sure.

In Judaic tradition there is language in the liturgy for Passover that I interpret that if the Creator had stopped at giving us the basics to survive it would have been enough. But we were gifted much more and so should count our blessings instead of whining. I think of that in my own life and how I communicate my expectations of that to others. I think of each of us working from baselines – there are things we can do and indeed do, but we shouldn’t just stop and say okay I did my bit now I can sit back. There is much that I feel I should be doing and have a moral and ethical responsibility personally and professionally to accomplish. I think most of us struggle with that goal and with the reality we may never fully reach it. But that is okay – it’s not a competition. It’s just not stopping when we could do more that is important and finding the ways that sit well with our ideals to do it. In the end I want to look back on my life and know I did what was right by this blessed planet and be able to know it was enough.

LikeLike

Alejandro, your decision leaves me wondering whether a man like you wouldn’t be the right one for the job, after all.

I used to work for an environmental agency. When I joined, I was struck by the hypocrisy of many of my co-workers, who lived in a manner counter to their knowledge of environmental principles including near-urban subdivision homes, long car commutes and careless buying habits. I am far from perfect in this regard but it seemed many of them were not even aware of the schism in their lives.

LikeLike

Not hypocrisy, but unfortunate. You sound like the perfect candidate. Those with good intent and knowledge to make a difference must engage on both sides. Refusing to engage is akin to the current situation in the US congress. This is a very personal decision, and it should be, but Im sorry it didnt work out.

LikeLike

[…] Conservation hypocrisy. I am so proud of Alejandro for declining to take a position with Smithsonian Institute, which would track a new Pacific pipeline, which would emit more harm into the atmosphere beyond dangerous levels already. […]

LikeLike

I entirely agree wit the sentiment of your post. However, on the other hand, I would far rather someone educated and aware of these issues took up the job, than someone who was willing to ignore the consequences. Perhaps you could have driven it in a slightly more positive direction…

LikeLike

Wow! I certainly applaud Alejandro’s difficult decision and his search for information concerning the larger impacts of the fossil fuel industry. However, I worry that less qualified professionals might be the only ones going for positions like this, doing mediocre jobs and therefore also harming local biodiversity. So where to draw the line in what is clearly unethical or what would do better with a good professional inside the corporative structure?

Best,

Erika

LikeLike

It’s funny to be responding to this post (and the subsequent comments that raise the same questions) in this forum, because I am Alejandro’s wife. Yet these comments are interesting in that they raise some good questions that we never discussed in our household about where we place our efforts in the Climate Movement. Sometimes if we take too firm an ethical stand, we can move our ethics to the fringes of the larger socio-political conversations that are going on around us. But on the other hand, if we set no standards than we are complicit. Sadly, we likely often lose our best talent in the work force and in society generally to the fringes. Thanks to all for your comments and the conversation about some difficult choices.

LikeLike

Dear Gail,

Thanks for your reply and, most importantly, thanks to you and Alejandro for sharing this experience in a blog with over 3000 followers and initiating a much needed ethical debate. Also, thanks for Bradshaw to host this post.

LikeLike

Deep respect and awe to Alejandro. I think you have made the right decision.

Curiously, I was in a similar situation some years ago. You can find my story and my decision here: http://wp.me/p2I4nE-9I

LikeLike

I applaud you Alejandro.

And I would most certainly argue that details at this point do not improve any widespread understanding of the issues. As Shane has demonstrated, they merely serve to provide distraction from action.

However, I do think that this as an example of the nobility of conservationists should be projected onto the international stage and become news, in an attempt to promote a widespread understanding that “unless someone like you cares a whole awful lot, nothing is going to get better. It’s not” (Dr Suess).

LikeLike

Dear Alejandro,

Your article states cumulative emissions in 2012 were 52 Gt of Carbon.

That’s equivalent to (52 GtC * 3.667) = 190.864 GtCO2

The World Bank’s Turn Down the Heat report states:

“Emissions of CO2 are, at present, about 35,000 million metric tons per year (including land-use change) and, absent further policies, are projected to rise to 41,000 million metric tons of CO2 per year in 2020.”

Therefore your figure of 190.684 GtCO2 is much larger than the World Bank’s report figure of 35 GtC. Other references are in the World Bank’s ballpark.

I’m not able to read your reference because I don’t have a Nature subscription and am not employed by anyone who does.

Sounds pedantic but if there’s any hope of widespread understanding about this issue then detail must be correct. Can you please check your figures? I’m happy to help.

This reference also provides useful info: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/cabot/events/2012/194.html

LikeLike

Shane,

Like you, I believe that accuracy=credibility=clarity, so I thank you for your comment. Below is the clarification for what I wrote and resolve any apparent discrepancies.

1) Rogelj et al. (Nature Climate Change 2013, 3:405-412) wrote that ‘Present emissions are slightly above 50 GtCO2e yr-1 (ref 33)’. I checked that reference (Montzka et al. 2011, Nature 476:43-60.), where Fig. 1 matches the statement by Rogelj et al. The slightly higher number I used in my letter (52 Gt), comes from an interview by journalist Stephen Leahy (http://www.ipsnews.net/2012/12/at-the-edge-of-the-carbon-cliff/) in which Rogelj ‘guesstimates’ the figure for 2012 based on current trends.

2) The apparent discrepancy between the above figures and the 35 GtCO2e yr-1 estimated by the World Bank report that you point out is explained by Non-CO2 greenhouse gases (CH4, N2O, etc), which Montzka et al. include in their total and the World Bank report does not. If you look at Figure 1 of Montzka et al., it all becomes quite clear.

3) My own mistake in my letter to the Smithsonian was to express the figure quoted from Rogelj et al. in terms of ‘Carbon Equivalent’, when I should have been writing in terms of ‘Carbon Dioxide Equivalent’. As you point out, the two units differ by a factor of 3.7, so I apologize by my lack of clarity in this regard. Lesson learned.

LikeLike