When I was in Finland last year, I had the pleasure of meeting Tomas Roslin and hearing him describe his Finland-wide citizen-science project on dung beetles. What impressed me most was that it completely flipped my general opinion about citizen science and showed me that the process can be useful.

I’m not trying to sound arrogant or scientifically elitist here – I’m merely stating that it was my opinion that most citizen-science endeavours fail to provide truly novel, useful and rigorous data for scientific hypothesis testing. Well, I must admit that I still believe that ‘most’ citizen-science data meet that description (although there are exceptions – see here for an example), but Tomas’ success showed me just how good they can be.

So what’s the problem with citizen science? Nothing, in principle; in fact, it’s a great idea. Convince keen amateur naturalists over a wide area to observe (as objectively) as possible some ecological phenomenon or function, record the data, and submit it to a scientist to test some brilliant hypothesis. If it works, chances are the data are of much broader coverage and more intensively sampled than could ever be done (or afforded) by a single scientific team alone. So why don’t we do this all the time?

If you’re a scientist, I don’t need to tell you how difficult it is to design a good experimental sampling regime, how even more difficult it is to ensure objectivity and precision when sampling, and the fastidiousness with which the data must be recorded and organised digitally for final analysis. And that’s just for trained scientists! Imagine an army of well-intentioned, but largely inexperienced samplers, you can quickly visualise how the errors might accumulate exponentially in a dataset so that it eventually becomes too unreliable for any real scientific application.

So for these reasons, I’ve been largely reluctant to engage with large-scale citizen-science endeavours. However, I’m proud to say that I have now published my first paper based entirely on citizen science data! Call me a hypocrite (or a slow learner).

Last year I was approached by my friend (and now, colleague), Professor Chris Daniels from the University of South Australia and Mount Lofty Ranges Natural Resource Management Board who is most well-known for his work in urban ecology. Together with Philip Roetman (UniSA) and Andrew Baker (CSIRO), he designed and implemented South Australia’s first Great Koala Count in 2012 – a citizen-science project aiming to quantify the distribution and abundance of koalas mainly in the Adelaide region. Of course, the Great Koala Count was also designed to inform the general public a little more about the koalas (literally) in their back gardens.

What really made the difference with this project was that a special smartphone app was designed to record the data during the 1-day survey. All the citizen scientist had to do was download the app (for iPhone or Android) and take a photo of any koalas seen on the day of the survey. The app would generate a coordinate and the data (including many ancillary questions) were sent to a central server managed by the Atlas of Living Australia. The app itself provided excellent location data as well as a confirmatory photo that could be followed up for quality control.

But what does one do with a whole heap of location data for a single species? If you are an ecologist, you generally would create a species distribution model to estimate the habitat suitability of the species in question across its sampled range (and perhaps beyond). Species distribution models are excellent tools for abundance estimates, monitoring range changes and even predicting how a species might fair in the future as habitats change due to human changes to the landscape (including climate change).

So with this excellent, first-time-ever, South Australian koala database, Chris and colleagues asked me to assist in analysing the data and writing the paper. With the help of my former PhD student, Ana Sequeira (who led the analysis and writing), we have just published the paper online in the journal Ecology and Evolution (Distribution models for koalas in South Australia using citizen science-collected data). In the true spirit of citizen science, the paper is also open-access (i.e., free, thanks to Phil for paying the open-access fees).

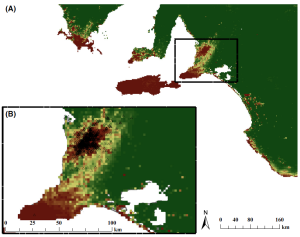

The species distribution model arising gives a pretty good prediction of the current and potential distribution of koalas in South Australia, plus a preliminary (albeit wide-ranging) population estimate for the Mount Lofty Ranges (about 100,000 koalas, give or take about 70,000).

Of course, the app couldn’t solve all problems such as biased sampling regimes (most people only looked near roads), lack of ‘absence’ data (people generally only wanted to report when they saw a koala, not when they didn’t) and only a single (very hot) day for the survey, the statistical techniques we employed helped alleviate some of the problems the database contained. Given this experience, we’ve learned a few things about how future surveys – and hopefully there will be another one next year – could be improved to maximise the scientific potential of the data collected.

So thanks to Chris, Philip, Andrew and especially Ana, for their hard work and excellent endeavour. I hope to be involved in the next iteration of the Great Koala Count, and will be certainly open to examining other citizen-science databases.

[…] koalas, so no need to labour the topic too much more, except to say that it is a thorny issue that I’ve mentioned before, as well as currently running a research programme to discern the most feasible management […]

LikeLike

[…] GKC2 and we need help to analyse them. Just as a little reminder, the GKCs are designed to provide better data to estimate the distribution and density of koalas in South Australia (especially in the Mount Lofty Ranges). We’ve already written one scientific article from […]

LikeLike

Corey, I think you nailed it when you said the scientists are doing science with information collected by citizens, or as you said in the article these are amateurs collecting data and submitting them to scientists to test hypotheses. This process is probably better termed citizen data collection or using citizens as field techs, which is an important but limited aspect of Citizen Science. When citizens are engaged in hypotheses generation, and data analysis, visualization and dissemination, then they are truly engaging in the process of science. But baby steps, right?

LikeLike

This understandable hesitancy is the reason that one of the first things we did at CosmoQuest was pit our citizen scientists against 8 experts in planetary science. They proved themselves quite capable! Probably a bit more controlled, having them in front of a computer screen rather than out and about, but still reassuring to do the study.

Great story. I wish we had koalas to count here in the US!

LikeLike

[…] The great koala count: Corey Bradshaw changes his mind about citizen science (sort of). (Conservation Bytes) […]

LikeLike

[…] The great koala count: Corey Bradshaw changes his mind about citizen science (sort of). (Conservation Bytes) […]

LikeLike

Great article, I recently made a film about Citizen Science.. the only one I know of so far https://www.facebook.com/pages/Whale-Chasers/347985945341872

LikeLike

There’s a recent article covering citizen science and it’s benefits. Projects cover biofuels, roadkill, seafloor biodiversity and others. Demonstrates how widely citizen science projects can reach, even in urban environments.

http://www.astc.org/blog/2014/04/28/powered-by-the-people-a-citizen-science-sampler/

The one thing that comes across to me from many of the citizen science projects I’ve looked into is the sheer number of people you can get involved and the amount of data you can generate. For example, since 1998 the Bird Atlas project has involved 7000 volunteers who have conducted over 420,000 surveys, comprising over 7.1 million bird records. Try getting that done with grant funding paying for your observers!

LikeLike

Well, launched in February 2010 was KoalaTracker – one of Australia’s largest and longest running citizen science projects (www.koalatracker.com.au). It’s goal is not to count koalas on a single day or weekend, but to map their locations, points of impact and causes of death and injury on an ongoing basis – so that effective risk mitigation can be undertaken, so that habitat can be protected, and our understanding grow. To see the value and impact of this – including the revelation of new information – watch the TEDx talk: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4fK0kGwg0Vk

LikeLike

Good job, and keep on. However, I think you missed the point of the post. It’s about doing science with the information collected by citizens. Your database might well fit the bill. We never claimed to be the first citizen-science endeavour for koalas, but it’s good to know we can tailor data collection to the rigorous requirements of hypothesis-driven science.

LikeLike

I’ll be talking about this paper & project tomorrow (01 May 2014) at 10.00 with Chris Daniels and host, Ian Henschke. You can live stream the interview here.

LikeLike

Hi Corey, I’ve been attempting to do something similar here in Brisbane to map and predict koala distribution but have faced a couple of issues: firstly, like you, I found a bias of sightings along roads and paths. My university campus is in the middle of a forest (Toohey Forest) which has had fluctuating koala distributions in the past. More and more sightings are reported in the area and I have started mapping those sightings. This was the foundation of a small student project. However, and this is my second issue, I since have struggled to come up with ways to encourage citizens to report sightings so as to increase the database. I have teamed up with Brisbane City Council who send me any sightings they may get but again I find these to be rather rare and sporadic. I’d love to have a chat to you about how to turn what I had hoped to be a citizen science project for mapping koala distribution in Brisbane into something feasible and rigorous, very much the way you and co-authors did.

Cheers

Lilia

LikeLike

You should definitely get in contact with co-author, Philip Roetman, who is organising a national approach to koala counts and analysis.

LikeLike

Corey,

Glad to see you’re realising the benefits of citizen science, as well as the potential for well designed apps to help gather data. I’m sure that the issue of the integrity of citizen science data has always been an impediment to many potential projects, but techniques may be improved with the formation of the Citizen Science Network Australia (http://citizenscience.org.au/wordpress/).

If you want a model citizen science project, you can’t do better than the Bird Atlas (http://www.birdlife.org.au/projects/atlas-and-birdata). Other ongoing projects look at frogs (http://frogs.melbournewater.com.au/content/get_involved/get_involved.asp), fungi (https://fungimap.org.au/), feral animals (http://www.feralscan.org.au/default.aspx), field monitoring (http://vnpa.org.au/page/volunteer/naturewatch) and even the whiskers of sea lions (http://whiskerpatrol.org/about/what-are-we-doing/). I’m sure you can find a citizen science project to further your interest and get you involved.

LikeLike

Thanks for the links and information. I’ll definitely look into these.

LikeLike