The more I delve into the science of predator management, the more I realise that the science itself takes a distant back seat to the politics. It would be naïve to think that the management of dingoes in Australia is any more politically charged than elsewhere, but once you start scratching beneath the surface, you quickly realise that there’s something rotten in Dubbo.

The more I delve into the science of predator management, the more I realise that the science itself takes a distant back seat to the politics. It would be naïve to think that the management of dingoes in Australia is any more politically charged than elsewhere, but once you start scratching beneath the surface, you quickly realise that there’s something rotten in Dubbo.

My latest contribution to this saga is a co-authored paper led by Dale Nimmo of Deakin University (along with Simon Watson of La Trobe and Dave Forsyth of Arthur Rylah) that came out just the other day. It was a response to a rather dismissive paper by Matt Hayward and Nicky Marlow claiming that all the accumulated evidence demonstrating that dingoes benefit native biodiversity was somehow incorrect.

Their two arguments were that: (1) dingoes don’t eradicate the main culprits of biodiversity decline in Australia (cats & foxes), so they cannot benefit native species; (2) proxy indices of relative dingo abundance are flawed and not related to actual abundance, so all the previous experiments and surveys are wrong.

Some strong accusations, for sure. Unfortunately, they hold no water at all.

First, the first contention is entirely a straw man of their own making. Just because dingoes do not eradicate foxes or cats from any particular area does not preclude positive effects. The mere presence of dingoes results nearly always in a suppression of cat and fox density, which means there are fewer depredations on native wildlife. As a population modeller, I can confirm that often it takes only a small reduction in mortality for a declining population to turn into a stable or increasing one, so any benefit dingoes can impart is a good thing. It is a strange argument to make that eradication must be a prerequisite for benefit.

In response to their second argument, it turns out that their chosen evidence that proxy indicators of relative dingo density (e.g., scat or track counts) was entirely cherry-picked; they in fact ignored a much broader literature demonstrating that real and proxy abundance indicators are tightly correlated for large predators globally. The argument is another form of a straw man as well because it would be nigh impossible to survey dingo density effectively and robustly over their vast ranges if we were required to rely on direct sightings or mark-recapture methods.

As CB.com readers will appreciate, I’m all for good scientific debate, but there’s an insidious underbelly to this dingo story that goes well beyond civilised scientific thrust and parry.

As some of you might well remember, we recently published a paper demonstrating the economic benefits of dingoes in semi-arid cattle ventures. The models were complex, but the ecological cascade is rather simple. More dingoes = more predation on (mainly) kangaroos = more grass = faster cattle growth rates & calf survival. Thus, it’s generally more profitable to have a healthy dingo population, even after accounting for the minor losses due to some dingo predation.

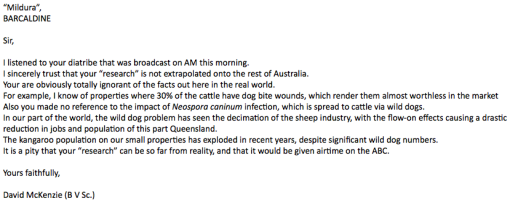

As was expected, some people didn’t like our results, and I received the consequent hate mail of which the following by a certain David McKenzie is a prime example:

—

What a wonderful contribution of intellectual engagement and decorum! (you can listen to my offending radio interview here).

I digress. Part of the problem is that such wild and unsubstantiated claims are thrown about with gay abandon to the extent that politicians, managers and certainly the average punter have no idea what’s going on. In other words, the science becomes irrelevant, and we get the spittle-flecked, vein-pulsing responses like the one from our erudite Mr McKenzie driving the agenda.

It’s not just the horrible welfare issues that poisoning and thousands of kilometres of fences have on our native wildlife, or the vast and growing body of real evidence showing that wildlife and pastoralism have something large to gain by having dingoes around, it’s the language and vested interests of outback ‘management’ that really gets me.

You’ll notice in almost any pastoral-friendly comment out there that the word ‘dingo’ almost never gets uttered. They are instead nearly always referred to as ‘wild dogs’. Now, that might not sound like such an important thing, but in fact, it is the heart and soul of the increasingly adversarial interaction between scientists, pastoralists and land managers. By referring to dingoes as ‘wild dogs’, there are strongly associated emotions of aversion and abomination. By using ‘dog’, the dingo is demeaned to a mere mongrel let loose by irresponsible humans, and by ‘wild’, we are meant to feel threatened by these raving carnivores roaming the country searching for their next bloody meal. Please.

It gets worse. Even some of our own government-funded research institutions refer to them almost exclusively as ‘wild dogs‘, with the inevitable corollary that their extensive commercial investments in poison baits and delivery systems are – wait for it – the only answers proffered to the vexing problem of all these horrid, nasty beasties destroying rural Australian lifestyles. Conflict of interest? I’ll let you decide.

[…] the following jobs he’s advertising for pest-animal control. Now, I’m near-completely opposed to ‘wild dog’ (i.e., dingo) control in Australia, but I’ve agreed to post the third position as well, despite my ecological […]

LikeLike

[…] Dingoes outcompete and kill introduced cats and foxes. Australia’s estimated 18 million feral cats, in particular, are a biodiversity scourge. To […]

LikeLike

Very simply, well said! The human dimensions, and more pointedly the socio-political dimensions, is the root of the problem here. How people frame dingoes and the cultural values or lack thereof is the real problem. As a human dimensional researcher I think this is one of your best pieces! Thank you!

LikeLike

Why, thank you. CJAB

LikeLike

If anybody is interested to read more about the title subject (i.e.’What’s in a name? The dingo’s sorry saga’), please refer to ‘Dingo – CSIRO Australian Natural History Series’ @ http://www.publish.csiro.au/pid/6430.htm. Alternatively you can watch this segment from Catalyst in 2009 http://www.abc.net.au/catalyst/stories/2589671.htm and my award winning documentary ‘The real dingo’ http://www.terramater.at/productions/the-real-dingo/from 2014.

LikeLike

arctic fox facts

Whats in a name? The dingos sorry saga | ConservationBytes.com

LikeLike

I’m also interested to know which side of this ‘political’ debate you’ve allocated to me Corey as I have members of both teams abusing me for calling your beloved indices into question. Your paper also utterly ignored the entire section we allocated to extolling the values of dingoes even if they don’t perform the mesopredator suppression you want them to.

Our paper aimed to explain how two groups of scientists who we viewed as honest could come up with diametrically opposed results. We believe this is because the methods are rubbish, and our response to your paper illustrates there is a large audience of international experts who agree. It is disappointing that the Journal hasn’t released both articles simultaneously as they said they would, so now folks must rely on politicised propaganda via blogs that lack peer review.

LikeLike

Around rural towns, how often are the ‘wild dogs’ peoples pets running loose of a night time? They don’t have to be wild or even strays – they can be owned and still cause trouble.

Something else I find hard to reconcile in my mind is how some people still think the way to manage stock is to eradicate any possible competition and predator. We’ve been domesticating sheep and cattle for centuries – we’ve taken the cow’s best defence by de-horning them, or breed some animals without horns to reduce our chance of being injured – all with the assumption that we’ll be able to protect the herd/flock and all they have to worry about is growing quickly &/or producing offspring so we can eat them.

Even after 200+ years of trying, this strategy hasn’t worked quite the way we thought it should, yet we keep on with the same plan. It’s expensive, and damages ecosystems when we keep trying to killing everything. Maybe it’s time for a change of tack?

LikeLike

There are plenty of animals around the world that get a bad rap after they become the center of conservation efforts, but the Canines seem to get a bizarrely bad rap. Here in the United States it’s wolves. People have outrageously strong feelings on wolves both positive and negative and, it seems, rarely in the middle. People are much more tolerable of cats, which as far as I know are also deadly to livestock and much more of a direct danger to people. Any thoughts on why people have such an averse reaction, in many cases outright hatred, to wild canines? Is it because we have such a love affair with the domestic dog and the wild relative is too close for comfort? Does it have anything to do with pack behavior? I’ve always been baffled and frustrated by this.

LikeLike

It’s interesting to note that many scientists are often shocked that people do not act rationally or in response to factual evidence. I am surprised that scientists are still under the illusion that facts cause the majority of people (you know, outside your ivory towers) to change their opinions and behaviour when history tells us this is hardly ever the case. The world is run by subjective, value-based judgements, not factual evidence, and the sooner scientists appreciate that, the better we’ll be.

LikeLike

I agree with your comment 100%, Niki.

However, where does this leave scientists? If members of the public aren’t swayed by factual evidence, should scientists then stop gathering such evidence? Double their efforts and gather more convincing evidence?

The world may be run by value-based judgements, but this doesn’t change the fact that it’s being run very poorly.

I suppose conservationists naively hope that damage-causing values can be changed with cold-hard facts (although I acknowledge that a lot of conservation science is shaped by the researchers implicit biases and is therefore not purely objective).

One solution may be for conservationists to devise management strategies that are robust to a variety of divergent values, but this runs the risk of creating strategies that are so flimsy that they become useless. Alternatively, conservationists must accept that their advice will create conflict with those with have divergent values. I don’t view this as a workable strategy either.

What would you suggest?

LikeLike

Firstly I think that we should not get our knickers in a twist when policy makers don’t do what we recommend. It may do us some good to get some training on policy science and social science in general so that we begin to understand the implications of our research and why it is that it is not being implemented.

I think there are various practical measures we could take to align values with facts, or at least to reduce conflict between divergent stakeholders. Co-producing knowledge is one option, consensus conferences another. Maybe we could take a leaf out of other disciplines’ textbooks and become more reflexive to appreciate the dynamic nature of these problems and how we play an integral part in causing and effecting them.

I agree that many conservationists are biased and the first step towards improving this situation is addressing it. Anthropologists are usually very forthcoming in this instance to convey how they believe their own skills and experience may influence their perception of reality – as well as how it will affect their outcomes.

Another step would be to appreciate that other people have equally valid points of view, so rather than openly mocking them in public it may be more conducive to sit down and talk to them to understand why it is they feel how they do towards these problems.

Lots of conservation problems are wicked; throwing more evidence at people is not going to change the deeply-ingrained social, political, religious, cultural, economic and historical factors that influence their values. Yes science is all about the pursuit of knowledge, but what is our end goal? To publish more journal articles or to actually make a positive difference for conservation?

LikeLike

Niki I can’t tell, based on the format of these comments, if you were responding to my comment or just adding another. It looks like you were just responding to the article but since you have a lot of thoughts on this I’m going to echo my questions from my first comment again. Yes, the world is governed by values which are always formed with varying degrees of subjectivity. Any ideas on why the canines seem to elicit particularly negative responses in people?

LikeLike

Hi Chris, there have been many theories as to why canids (and particularly wolves, coyotes, African wild dogs and dingoes) elicit such a stronger response than felids. Possibilities include:

1. The similarities between canids and humans (e.g. social, intelligent, cooperative, but this breaks down when including lions – although these too are hated when humans have to live with them)

2. As you point out, the familiarity with canids due to our 20,000 year history of domesticated dogs (compare with domestic cats, which were domesticated only a few thousand years ago and their close cousins, caracals/wildcats/servals etc.)

3. The face shape: dogs have long snouts, cats short so the latter apparently look cuter (there’s psychological research on this)

4. The canid’s amazing hunting ability (African wild dogs for example have a far higher hunting success than any of the big cat species)

5. The many myths and cultural symbols associated with wolves historically, mostly portrayed as evil (compare with big cats which are often symbolised as godly)

6. The fact that canids are in general more adaptable than felids (leopards possibly being the exception), which usually make them more prolific and therefore cause more perceived damage

There are probably many more reasons behind this too. Good question though!

LikeLike

Matt Hayward’s research to debunk Dingo benefits was funded by the WA DEC?? (Department of Extermination & Cruelty) the DEC’s 1080 program poisons half the state and they are completely dependent on its continued use. An independent review of Western Shield in 2003 recommended that the WA DEC look into the positive roles that Dingoes could play in the conservation of vulnerable WA native species. Those recommendations were ignored. 13 years later the DEC employed scientists are still on a propaganda Dingo killing rampage. Goebles would be proud..

LikeLike

My research isn’t funded by DEC or DPAW.

LikeLike

You’ll love our response to your paper then Corey.

LikeLike