I had an interesting exchange on Twitter today that deserves some discussion, not because the brief internet argument that ensued offers some insightful wisdom (internet debates rarely do anything more than identify all those involved as fuckwits), but because it raises an interesting issue in conservation.

I had an interesting exchange on Twitter today that deserves some discussion, not because the brief internet argument that ensued offers some insightful wisdom (internet debates rarely do anything more than identify all those involved as fuckwits), but because it raises an interesting issue in conservation.

The abbreviated (and slightly expurgated) main message of the exchange was whether drawing attention to the potential for a species to cause harm to humans is good or bad (for the species in question).

The elasmobranchologists in particular usually become apoplectic whenever anyone calls a shark ‘deadly’, or some such similar adjective. As it turns out, the ophidiologists appear to be equally sensitive. I admit that they do have a point — it’s probably fair to assume that films like Jaws and Anaconda (or, Darwin-forbid, Sharknado) haven’t done much to make most people appreciate the amazing diversity, evolutionary adaptations and wonderful life histories of these subclasses & clades (respectively).

In fact, most marine biologists assume that Jaws in particular was responsible for decades of overt prosecution of sharks that has led to the massive population declines. However, I sincerely wonder whether the bad media was in the real culprit and over-fishing was instead the principal cause of today’s observed shark declines (the questionable nature of the numbers often cited notwithstanding).

So I’ll finally get to my point — which turns out to be more of a question — do negative (fear-based) media campaigns do more harm than good when it comes to deadly (i.e., able to cause death) species? Does highlighting in some sensationalised television series or movie the fact that a white pointer can easily chomp you in half, or that a baby brown snake can off your three-year old in under two hours, lead to a worse conservation status for the taxa concerned? Does fear-based media coverage have no real conservation affect at all, or does it potentially lead to better conservation outcomes because of the public’s morbid fascination with the species involved?

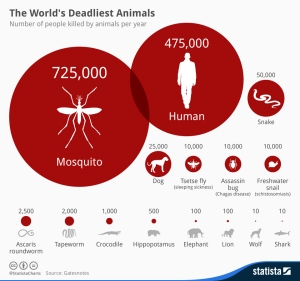

Most of you will have seen a version of the now-viral poster of relative ‘deadliness’ of various animal species, measured as the number of human fatalities arising per unit time (see the adjacent example). I haven’t checked these numbers but if you believe them, mosquitoes and humans (of course) are far deadlier than all other animals combined, with sharks way, way down the ladder. Nonetheless, most people are shit-scared of sharks even though the probability of being bitten by one is orders of magnitude less than getting into a car accident on the way to the beach. Biologists (myself included) sanctimoniously spread such posters around the interwebz in a ‘See? Sharks and snakes are actually quite lovely and you should love them’ sort of way (and I agree), but I really wonder who they (we) are trying to convince?

Most of you will have seen a version of the now-viral poster of relative ‘deadliness’ of various animal species, measured as the number of human fatalities arising per unit time (see the adjacent example). I haven’t checked these numbers but if you believe them, mosquitoes and humans (of course) are far deadlier than all other animals combined, with sharks way, way down the ladder. Nonetheless, most people are shit-scared of sharks even though the probability of being bitten by one is orders of magnitude less than getting into a car accident on the way to the beach. Biologists (myself included) sanctimoniously spread such posters around the interwebz in a ‘See? Sharks and snakes are actually quite lovely and you should love them’ sort of way (and I agree), but I really wonder who they (we) are trying to convince?

Fear doesn’t flow from the cerebral cortex; it has bugger all to do with empirical data. Yet people are fascinated by it. Why do millions of kids the world over go ga-ga when they read a shark story? Why are we fascinated with the things that could (but rarely do) kill us? My question can therefore be developed into an hypothesis that someone out there should endeavour to test: do modern-day, fear- (morbid fascination- ) based media exposées really do species harm, or is it much worse for a relatively benign species of which no one has heard a thing? To deform completely an old quote from Oscar Wilde, is the mere fact that people are interested in a topic (whatever their reasons) enough to shine a light on a species’ conservation plight, or does it always have to be sugar-coated message of positivity? Is there empirical evidence out there that cheesey, over-the-top, sensationalised television leads to population declines? I’d really like to know.

Granted, I bet the data will be hard to come by, but if there is anything out there at all of an empirical (cf. philosophical) nature, I’d be interested in hearing about it.

[…] https://conservationbytes.com/2015/10/13/only-thing-worse-than-being-labelled-deadly-is-not-being-cal… […]

LikeLike

Interesting post, and indeed there have been studies conducted on media content analysis, media framing of issues, and influences on social perception. The topic of Sharks and their conservation has recently featured in an article (http://authorservices.wiley.com/bauthor/onlineLibraryTPS.asp?DOI=10.1111/j.1523-1739.2012.01952.x&ArticleID=1061112), and there are others on climate change and risk perception; human-elephant conflict; human-black bear conflict; human-leopard conflict, etc. I myself am analyzing NAmerican media content in grizzly bear range to understand the framing of article(conflict topics, science topics, etc), representative anecdote and representative attitude the readership is left with…

LikeLike

Hi Courtney – thanks for these. I’m aware of most of the analyses of ‘perception’, but my question stands: does it actually influence conservation status of the species concerned? There appear to be a lot of assumptions, but little hard evidence that negative press = negative outcomes.

LikeLike

Agreed – I don’t immediately recall any work done, though think that marketing, economics, health, and perhaps behavioral psychology would have some studies of interest. Am going to do some digging :) Am curious to know your thoughts on how you would measure this? Applying the theory of planned behavior may be one way…any other ideas? Also, anecdotally from some work experience, I have observed that media appears to influence public perception, which in turn appears to influence whether or not the public supports a species’ designation or management plan, which then appears to influence the actual success or not of implementing conservation efforts. I know this is quite subjective, so wonder if you have thoughts on how one would measure this hypothesized impact? Thanks in advance for thoughts!

LikeLike

While I understand where they’re coming from, I’ve never cared for the ‘sharks cause fewer deaths than X’ lines. Surely the important metric isn’t total deaths, but total deaths based on unit exposure.

LikeLike

Ah, that point was touched on in another comment. Oops.

LikeLike

Hi, Dr. Bradshaw,

I have printed all 10 (+1 you later suggested) of the studies reccomended by you as (some) essential readings in consbio. I have read them all; studied them all. Except for the wonderful statistics papers, which are a bit daunting for me, I believe I “get” their points and purposes. I have alerted 3 local orgs about yr site. They focus on wet-land, riparian, estuary, and H2O mgmt issues here on the mid-e coast of Vancouver Island, British Columbia, Canada.

I grant that “thank you’s” and “understanding” are not the most heartening music for your ears. Hearing about ACTION is, really, the only tune that counts. Still, thanks for wesite’s presence. I suspect the evolution and maintenance of the site took–and takes–hours of your professional time, and probably lots of home time too, I hope collegues and employers support this public out-reach work.

Without knowedgeable non-professional support to push-pull govt.s into a consbio mode, professional (and volunteer) efforts are difficult to conduct, and much less likely have positive lasting consequences.

I especially wish to thank you for providing access to papers that are sequestered in various db’s that charge for copying. Most brag about their fee-free data–but such usually consists of material that is of only background or historical interest.

So, in fine, keep on keeping on. Your web work is important. It deserves professional recogniton and support. I am hopeful it receives lots of both.

Referencing your notes on socially induced fears, I recall from social anthropolgy studies that fears are important control strategies–usually of women and children. I wonder if relevant info might be available from fellow academics over at the Department of Anthropology. Maybe they could advise on some ways to generate fears of ecological collapse. A few coming-of-age ordeal drugs, a few nights alone in the bush, some chants and dances, and viola: A Conservationist citizen is welcomed into the tribe!

Regards, Larry Willams

LikeLike

Reblogged this on The Waterthrush Blog.

LikeLike

A rather different but interesting statistic would be ‘relative deadliness’ – number of humans killed per creature divided by estimated number of creatures. This would surely change the order!

Andrew Smith

LikeLike

Interesting post Corey. There’s a bit of statistical sleight of hand going on in those “World’s deadliest animals” pictures like the one you show. They show total number of deaths caused by X animal, fine. But is this “deadliest”?

If we define deadliest as the animal most likely to kill you when you come into contact with it, then we need to control for contact events. I used to think about this regularly while handling taipans. Sure only two people die each year in Australia from snake bite, but how many people came into contact with snakes? For argument sake, if only 5 people came into contact with snakes each year and 2 people die, then snakes are more lethal than ebola.

The humble mozzy gets plugged with killing more people than the crusades, but that’s because there’s so many of the buggers. In fact, picking on the mozzy is shooting the messenger, its malaria doing the killing. Not that I am sticking up for mozzy’s; I swat ’em quicker than a fat kid swats a skittle.

LikeLike