Rain forest gives way to pastures in the Brazilian Amazon in Mato Grosso. Photo by Thiago Foresti.

More than 600 scientists from every country in the EU and 300 Brazilian Indigenous groups have come together for the first time. This is because we see a window of opportunity in the ongoing trade negotiations between the EU and Brazil. In a Letter published in Science today, we are asking the EU to stand up for Brazilian Indigenous rights and the natural world. Strong action from the EU is particularly important given Brazil’s recent attempts to dismantle environmental legislation and ‘develop the unproductive Amazon’.

It’s worth clarifying — this isn’t about the EU trying to control Brazil — it’s about making sure our imports aren’t driving violence and deforestation. Foreign white people trying to ‘protect nature’ abroad have a dark and shameful past, where actions done in the name of conservation have led to the eviction of millions of Indigenous people. This has predominantly been to create (what we in the world of conservation would call) ‘protected areas’. The harsh reality is that most protected areas either are or have been ancestral lands of Indigenous people who are closely linked to their land and depend on it for their survival. Clearly, conservationists need to support Indigenous people. This new partnership between European scientists and Brazilian Indigenous groups is doing just that.

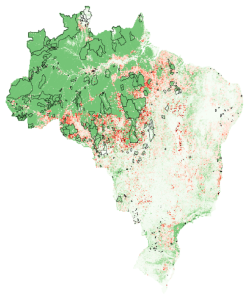

Brazil’s forest loss 2001-2013 shown in red. Indigenous lands outlined. By Mike Clark; data from GlobalForestWatch.org

In Brazil, many Indigenous groups still have a right to their land. This land is predominantly found in the Amazon rainforest, where close to a million Indigenous people live and depend on a healthy forest. Indigenous people are some of the best protectors of this vast forest, and are crucial to a future of long-term successful conservation. But Brazilian Indigenous groups and local communities are increasingly under attack. Violence on deforestation frontiers in Brazil has spiked this month, with at least 9 people found dead. The future is particularly scary for Indigenous people when there are quotes such as this from the man who is currently the President “It’s a shame that the Brazilian cavalry hasn’t been as efficient as the Americans, who exterminated the Indians.”

On top of human rights and environmental concerns, there is a strong profit driven case for halting deforestation. For example, ongoing deforestation in the Amazon risks flipping large parts of the rainforest to savanna – posing a serious risk to agricultural productivity, food security, local livelihoods, and the Brazilian economy. Zero-deforestation doesn’t harm agri-business, it allows for its longevity. Read the rest of this entry »