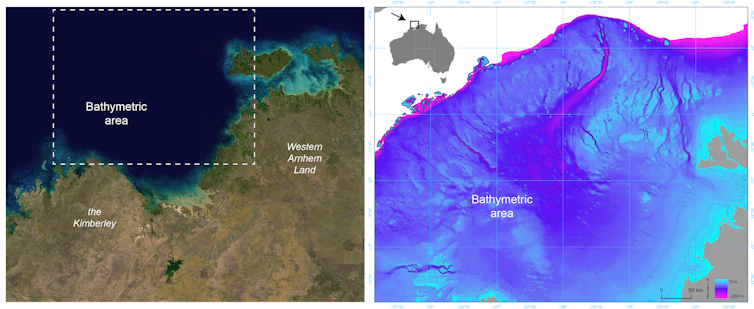

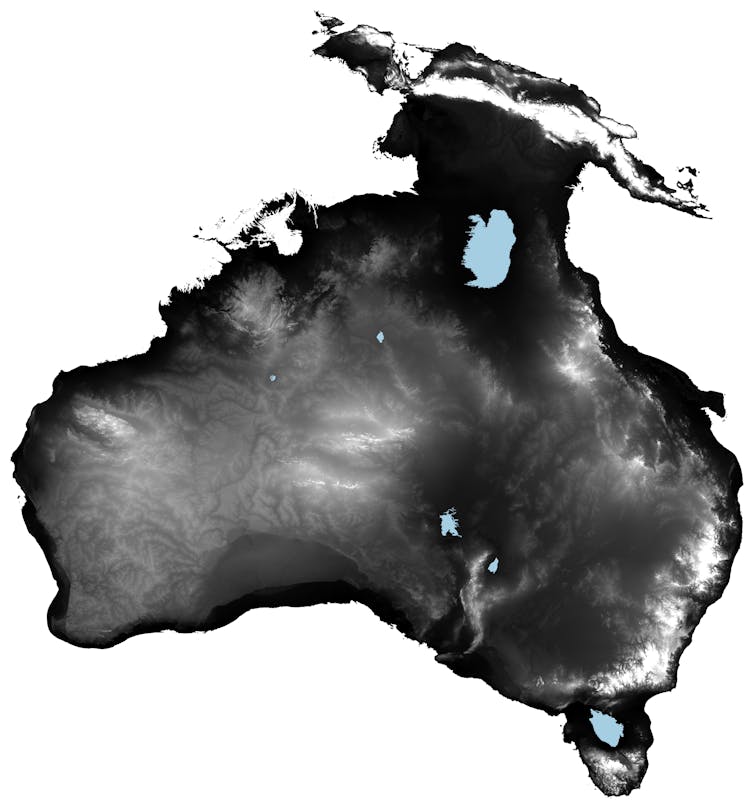

For much of the 65,000 years of Australia’s human history, the now-submerged northwest continental shelf connected the Kimberley and western Arnhem Land. This vast, habitable realm covered nearly 390,000 square kilometres, an area one-and-a-half times larger than New Zealand is today.

It was likely a single cultural zone, with similarities in ground stone-axe technology, styles of rock art, and languages found by archaeologists in the Kimberley and Arnhem Land.

There is plenty of archaeological evidence humans once lived on continental shelves – areas that are now submerged – all around the world. Such hard evidence has been retrieved from underwater sites in the North Sea, Baltic Sea and Mediterranean Sea, and along the coasts of North and South America, South Africa and Australia.

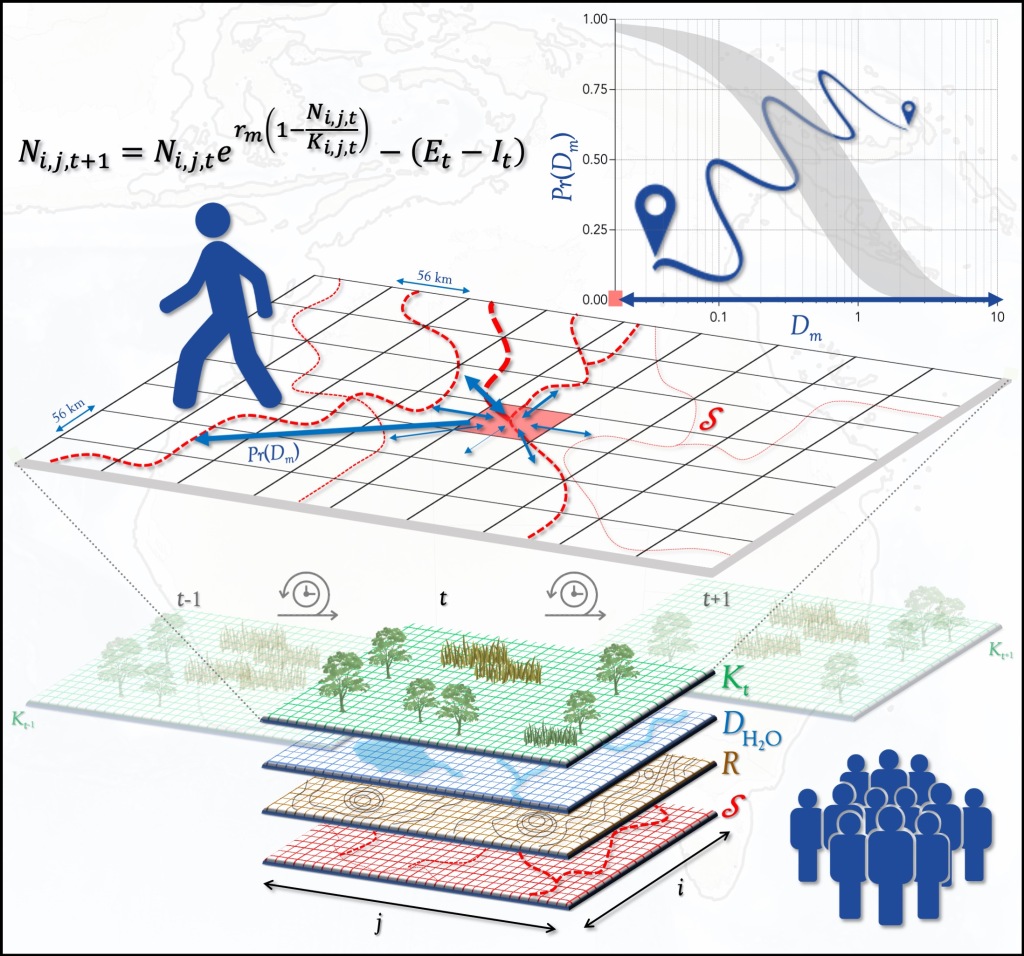

In a newly published study in Quaternary Science Reviews, we reveal details of the complex landscape that existed on the Northwest Shelf of Australia. It was unlike any landscape found on our continent today.

A continental split

Around 18,000 years ago, the last ice age ended. Subsequent warming caused sea levels to rise and drown huge areas of the world’s continents. This process split the supercontinent of Sahul into New Guinea and Australia, and cut Tasmania off from the mainland.

Unlike in the rest of the world, the now-drowned continental shelves of Australia were thought to be environmentally unproductive and little used by First Nations peoples.

But mounting archaeological evidence shows this assumption is incorrect. Many large islands off Australia’s coast – islands that once formed part of the continental shelves – show signs of occupation before sea levels rose.

Stone tools have also recently been found on the sea floor off the coast of the Pilbara region of Western Australia.

Read the rest of this entry »

What’s in a name? Well, rather a lot, I think.

What’s in a name? Well, rather a lot, I think.