Shutterstock

Science fiction is rife with fanciful tales of deadly organisms emerging from the ice and wreaking havoc on unsuspecting human victims.

From shape-shifting aliens in Antarctica, to super-parasites emerging from a thawing woolly mammoth in Siberia, to exposed permafrost in Greenland causing a viral pandemic – the concept is marvellous plot fodder.

But just how far-fetched is it? Could pathogens that were once common on Earth – but frozen for millennia in glaciers, ice caps and permafrost – emerge from the melting ice to lay waste to modern ecosystems? The potential is, in fact, quite real.

Dangers lying in wait

In 2003, bacteria were revived from samples taken from the bottom of an ice core drilled into an ice cap on the Qinghai-Tibetan plateau. The ice at that depth was more than 750,000 years old.

In 2014, a giant “zombie” Pithovirus sibericum virus was revived from 30,000-year-old Siberian permafrost.

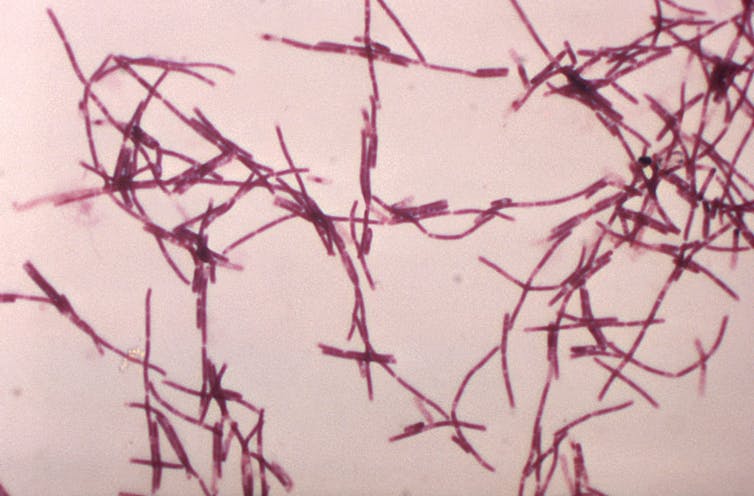

And in 2016, an outbreak of anthrax (a disease caused by the bacterium Bacillus anthracis) in western Siberia was attributed to the rapid thawing of B. anthracis spores in permafrost. It killed thousands of reindeer and affected dozens of people.

William A. Clark/USCDCP

More recently, scientists found remarkable genetic compatibility between viruses isolated from lake sediments in the high Arctic and potential living hosts.

Earth’s climate is warming at a spectacular rate, and up to four times faster in colder regions such as the Arctic. Estimates suggest we can expect four sextillion (4,000,000,000,000,000,000,000) microorganisms to be released from ice melt each year. This is about the same as the estimated number of stars in the universe.

However, despite the unfathomably large number of microorganisms being released from melting ice (including pathogens that can potentially infect modern species), no one has been able to estimate the risk this poses to modern ecosystems.

In a new study published today in the journal PLOS Computational Biology, we calculated the ecological risks posed by the release of unpredictable ancient viruses.