While some complain that the European Union (EU) is an enormous, cumbersome beast (just ask the self-harming Brexiteers), it generally has some rather laudable legislative checks and balances for nature conservation. While far from perfect, the rules applying to all Member States have arguably improved the state of both European environments, and those from which Europeans source their materials.

While some complain that the European Union (EU) is an enormous, cumbersome beast (just ask the self-harming Brexiteers), it generally has some rather laudable legislative checks and balances for nature conservation. While far from perfect, the rules applying to all Member States have arguably improved the state of both European environments, and those from which Europeans source their materials.

But legislation gets updated from time to time, and not always in the ways that benefit biodiversity (and therefore, us) the most. This is exactly what’s just happened with the new EU Renewable Energy Directive (RED) released in June this year.

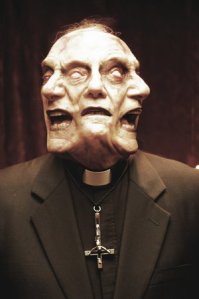

Now, this is the point where most readers’ eyes glaze over. EU policy discussions are exceedingly dry and boring (I’ve dabbled a bit in this arena before, and struggled to stay awake myself). But I’ll try to lighten your required concentration load somewhat by being as brief and explanatory as possible, but please stay with me — this shit is important.

In fact, it’s so important that I joined forces with some German colleagues with particular expertise in greenhouse-gas accounting and EU policy — Klaus Hennenberg and Hannes Böttcher1 of Öko-Institut (Institute of Applied Ecology) in Darmstadt — to publish an article available today in Nature Ecology and Evolution.

So back to the RED legislation. The original ‘RED 2009‘ covered reductions of greenhouse-gas emissions and the mitigation of negative impacts on areas of high biodiversity value, such as primary forests, protected areas, and highly biodiverse grasslands, and for areas of high carbon stock like wetlands, forests, and peatlands.

So back to the RED legislation. The original ‘RED 2009‘ covered reductions of greenhouse-gas emissions and the mitigation of negative impacts on areas of high biodiversity value, such as primary forests, protected areas, and highly biodiverse grasslands, and for areas of high carbon stock like wetlands, forests, and peatlands.

But RED 2009 was far from what we might call ‘ambitious’, because globally mandatory criteria on water, soil and social aspects for agriculture and forestry production were excluded to avoid conflicts with rules of the World Trade Organization.

Nor did RED 2009 apply to all bioenergy types, and only included biofuels used in transport, including gaseous and solid fuels, and bioliquids used for electricity, heating, and cooling. But RED 2009 requirements also applied to all raw materials sourced from agriculture and forestry, especially as forest biomass is explicitly mentioned as a raw material for the production of advanced biofuels in the RED 2009 extension from 2015.

Thus, one could conceivably call RED 2009 criteria ‘minimum safeguards’.

But as of June this year, the EU accepted a 2016 proposal to recast RED 2009 into what is now called ‘RED II’. While the revisions might look good on paper by setting new incentives in transport (advanced biofuels) and in heating and cooling that will likely increase the use of biomass sourced from forests, and by extending the directive on solid and gaseous biomass, the amendments unfortunately take some huge leaps backwards in terms of sustainability requirements.

These include the following stuff-ups: Read the rest of this entry »