The way that eels migrate along rivers and seas is mesmerising. There has been scientific agreement since the turn of the 20th Century that the Sargasso Sea is the breeding home to the sole European species. But it has taken more than two centuries since Carl Linnaeus gave this snake-shaped fish its scientific name before an adult was discovered in the area where they mate and spawn.

Even among nomadic people, the average human walks no more than a few dozen kilometres in a single trip. In comparison, the animal kingdom is rife with migratory species that traverse continents, oceans, and even the entire planet (1).

The European eel (Anguilla anguilla) is an outstanding example. Adults migrate up to 5000 km from the rivers and coastal wetlands of Europe and northern Africa to reproduce, lay their eggs, and die in the Sargasso Sea — an algae-covered sea delimited by oceanic currents in the North Atlantic.

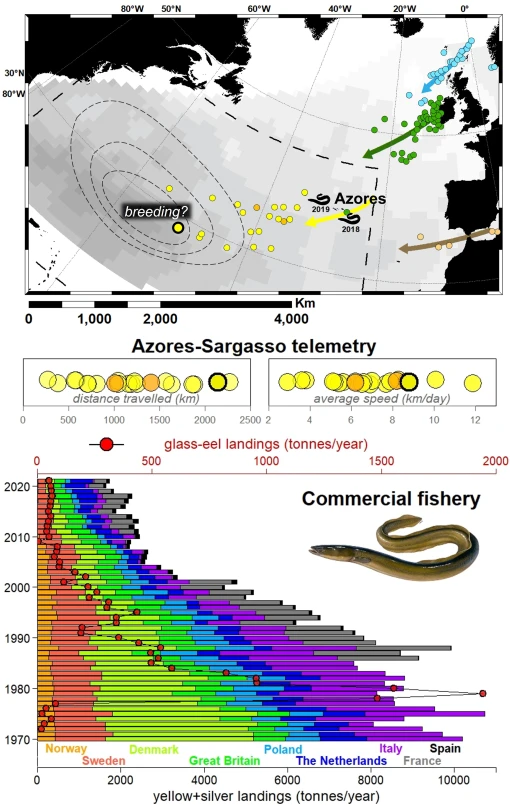

As larvae emerge, they drift with the prevailing marine currents over the Atlantic to the European and African coasts (2). The location of the breeding area was unveiled in the early 20th Century as a result of the observation that the size of the larvae caught in research surveys gradually decreased from Afro-European land towards the Sargasso Sea (3, 4). Adult eels had been tracked by telemetry in their migration route converging on the Azores Archipelago (5), but none had been recorded beyond until recently.

Crossing the Atlantic

To complete this piece of the puzzle, Rosalind Wright and collaborators placed transmitters in 21 silver females and released them in the Azores (6). These individuals travelled between 300 and 2300 km, averaging 7 km each day. Five arrived in the Sargasso Sea, and one of them, after a swim of 243 days (from November 2019 to July 2020), reached what for many years had been the hypothetical core of the breeding area (3, 4). It is the first direct record of a European eel ending its reproductive journey.

Eels use the magnetic fields in their way back to the Sargasso Sea and rely on an internal compass that records the route they made as larvae (7). The speed of navigation recorded by Wright is slower than in many long-distance migratory vertebrates like birds, yet it is consistent across the 16 known eel species (8).

Wright claimed that, instead of swiftly migrating for early spawning, eels engage in a protracted migration at depth. This behaviour serves to conserve their energy and minimises the risk of dying (6). The delay also allows them to reach full reproductive potential since, during migration, eels stop eating and mobilise all their resources to swim and reproduce (9).

Other studies have revealed that adults move in deep waters in daylight but in shallow waters at night, and that some individuals are faster than others (3 to 47 km per day) (5). Considering that (i) this fish departs Europe and Africa between August and December and (ii) spawning occurs in the Sargasso Sea from December to May, it is unknown whether different individuals might breed 1 or 2 years after they begin their oceanic migration.

Management as complex as life itself

The European eel started showing the first signs of decline at the end of the 19th Century (10, 11). In 2008, the species was listed as Critically Endangered by the IUCN, and its conservation status has since remained in that category — worse than that of the giant panda (Ailuropoda melanoleuca) or the Iberian lynx (Lynx pardinus).

Read the rest of this entry »