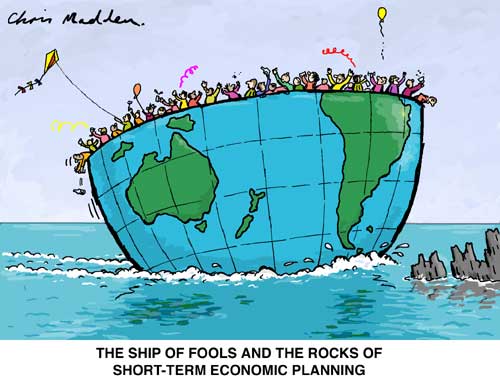

As humanity plunders its only home and continues destroying the very life that sustains our ‘success’, certain concepts in ecology, evolution and conservation biology are being examined in greater detail in an attempt to apply them to restoring at least some elements of our ravaged biodiversity.

As humanity plunders its only home and continues destroying the very life that sustains our ‘success’, certain concepts in ecology, evolution and conservation biology are being examined in greater detail in an attempt to apply them to restoring at least some elements of our ravaged biodiversity.

One of these concepts has been largely overlooked in the last 30 years, but is making a conceptual comeback as the processes of extinction become better quantified. The so-called Allee effect can be broadly defined as a “…positive relationship between any component of individual fitness and either numbers or density of conspecifics” (Stephens et al. 1999, Oikos 87:185-190) and is attributed to Warder Clyde Allee, an American ecologist from the early half of the 20th century, although he himself did not coin the term. Odum referred to it as “Allee’s principle”, and over time, the concept morphed into what we now generally call ‘Allee effects’.

Nonetheless, I’m using Allee’s original 1931 book Animal Aggregations: A Study in General Sociology (University of Chicago Press) as the Classics citation here. In his book, Allee discussed the evidence for the effects of crowding on demographic and life history traits of populations, which he subsequently redefined as “inverse density dependence” (Allee 1941, American Naturalist 75:473-487).

What does all this have to do with conservation biology? Well, broadly speaking, when populations become small, many different processes may operate to make an individual’s average ‘fitness’ (measured in many ways, such as survival probability, reproductive rate, growth rate, et cetera) decline. The many and varied types of Allee effects can work together to drive populations even faster toward extinction than expected by chance alone because of self-reinforcing feedbacks (see also previous post on the small population paradigm). Thus, ignorance of potential Allee effects can bias everything from minimum viable population size estimates, restoration attempts and predictions of extinction risk.

A recent paper in the journal Trends in Ecology and Evolution by Berec and colleagues entitled Multiple Allee effects and population management gives a more specific breakdown of Allee effects in a series of definitions I reproduce here for your convenience:

Allee threshold: critical population size or density below which the per capita population growth rate becomes negative.

Anthropogenic Allee effect: mechanism relying on human activity, by which exploitation rates increase with decreasing population size or density: values associated with rarity of the exploited species exceed the costs of exploitation at small population sizes or low densities (see related post).

Component Allee effect: positive relationship between any measurable component of individual fitness and population size or density.

Demographic Allee effect: positive relationship between total individual fitness, usually quantified by the per capita population growth rate, and population size or density.

Dormant Allee effect: component Allee effect that either does not result in a demographic Allee effect or results in a weak Allee effect and which, if interacting with a strong Allee effect, causes the overall Allee threshold to be higher than the Allee threshold of the strong Allee effect alone.

Double dormancy: two component Allee effects, neither of which singly result in a demographic Allee effect, or result only in a weak Allee effect, which jointly produce an Allee threshold (i.e. the double Allee effect becomes strong).

Genetic Allee effect: genetic-level mechanism resulting in a positive relationship between any measurable fitness component and population size or density.

Human-induced Allee effect: any component Allee effect induced by a human activity.

Multiple Allee effects: any situation in which two or more component Allee effects work simultaneously in the same population.

Nonadditive Allee effects: multiple Allee effects that give rise to a demographic Allee effect with an Allee threshold greater or smaller than the algebraic sum of Allee thresholds owing to single Allee effects.

Predation-driven Allee effect: a general term for any component Allee effect in survival caused by one or multiple predators whereby the per capita predation-driven mortality rate of prey increases as prey numbers or density decline.

Strong Allee effect: demographic Allee effect with an Allee threshold.

Subadditive Allee effects: multiple Allee effects that give rise to a demographic Allee effect with an Allee threshold smaller than the algebraic sum of Allee thresholds owing to single Allee effects.

Superadditive Allee effects: multiple Allee effects that give rise to a demographic Allee effect with an Allee threshold greater than the algebraic sum of Allee thresholds owing to single Allee effects.

Weak Allee effect: demographic Allee effect without an Allee threshold.

For even more detail, I suggest you obtain the 2008 book by Courchamp and colleagues entitled Allee Effects in Ecology and Conservation (Oxford University Press).

CJA Bradshaw

(Many thanks to Salvador Herrando-Pérez for his insight on terminology)