A quick post to talk about a subject I’m more and more interested in – the direct link between environmental degradation (including biodiversity loss) and human health.

A quick post to talk about a subject I’m more and more interested in – the direct link between environmental degradation (including biodiversity loss) and human health.

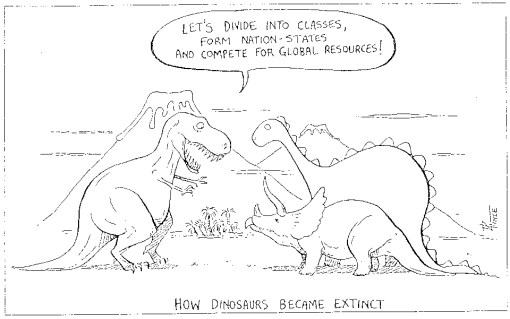

To many conservationists, people are the problem, and so they focus naturally on trying to maintain biodiversity in spite of human development and spread. Well, it’s 60+ years since we’ve been doing ‘conservation biology’ and biodiversity hasn’t been this badly off since the Cretaceous mass extinction event 146-64 million years ago. We now sit squarely within the geological era more and more commonly known as the ‘Anthropocene’, so if we don’t consider people as an integral part of any ecosystem, then we are guaranteed to fail biodiversity.

I haven’t posted in a week because I was in Shanghai attending the rather clumsily entitled “Thematic Reference Group (TRG) on Environment, Agriculture and Infectious Disease’, which is a part of the UNICEF/UNDP/World Bank/World Health Organization Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases (TDR) (what a mouthful that is). What’s this all about and why is a conservation ecologist (i.e., me) taking part in the group?

It’s taken humanity a while to realise that what we do to the planet, we eventually end up doing to ourselves. The concept of ecosystem services1 demonstrates this rather well – our food, weather, wealth and well-being are all derived from healthy, functioning ecosystems. When we start to bugger up the inter-species relationships that define one element of an ecosystem, then we hurt ourselves. I’ve blogged about this topic a few times before with respect to flooding, pollination, disease emergence and carbon sequestration.

Our specific task though on the TRG is to define the links between environmental degradation, agriculture, poverty and infectious disease in humans. Turns out, there are quite a few examples of how we’re rapidly making ourselves more susceptible to killer infectious diseases simply by our modification of the landscape and seascape.

Some examples are required to illustrate the point. Schistosomiasis is a snail-borne fluke that infects millions worldwide, and it is on the rise again from expanding habitat of its host due to poor agricultural practices, bad hygiene, damming of large river systems and climate warming. Malaria too is on the rise, with greater and greater risk in the endemic areas of its mosquito hosts. Chagas (a triatomine bug-borne trypanosome) is also increasing in extent and risk. Some work I’m currently doing under the auspices of the TRG is also showing some rather frightening correlations between the degree of environmental degradation within a country and the incidence of infectious disease (e.g., HIV, malaria, TB), non-infectious disease (e.g., cancer, cardiovascular disease) and indices of life expectancy and child mortality.

I won’t bore you with more details of the group because we are still drafting a major World Health Organization report on the issues and research priorities. Suffice it to say that if we want to convince policy makers that resilient functioning ecosystems with healthy biodiversity are worth saving, we have to show them the link to infectious disease in humans, and how this perpetuates poverty, rights injustices, gender imbalances and ultimately, major conflicts. An absolute pragmatist would say that the value of keeping ecosystems intact for this reason alone makes good economic sense (treating disease is expensive, to say the least). A humanitarian would argue that saving human lives by keeping our ecosystems intact is a moral obligation. As a conservation biologist, I argue that biodiversity, human well-being and economies will all benefit if we get this right. But of course, we have a lot of work to do.

CJA Bradshaw

1Although Bruce Wilcox (another of the TRG expert members), who I will be highlighting soon as a Conservation Scholar, challenges the notion of ecosystem services as a tradeable commodity and ‘service’ as defined. More on that topic soon.

I begin with the proverbial WTF? The title of this post sounds a little like the legalese accompanying a witchcraft trial, but it’s jargon that’s all the rage in the ‘trading-carbon-for-biodiversity’ circles.

I begin with the proverbial WTF? The title of this post sounds a little like the legalese accompanying a witchcraft trial, but it’s jargon that’s all the rage in the ‘trading-carbon-for-biodiversity’ circles.

An excellent

An excellent