As someone who regularly delves into human demography — often from a conservation perspective — I’m always on the lookout for quick and easy ways to get the latest and greatest datasets. Whether it’s for projection human populations, or just getting country-specific population densities, I’ve found a really nice way to interface great human data with R.

In this particular example, I’m using a api (application programming interface) key to access live data on the US Census Bureau server (don’t worry — they have global data, not just those specific to the US). What’s an ‘api key’? It’s just a code that gives you permission to access the server directly from an application via an internet link.

Step 1. Apply for an api key

This is a straightforward process and just needs to be done via this URL. The approval process doesn’t take long.

Step 2: Install the idbr package in R

This stands for the ‘(US Census Bureau) International Data Base (R)’, and grants access to and queries demographic data, including contemporary, historical, and future projections to 2100 for countries with ≥ 5000 people.

install.packages(“idbr”)

Step 3: Set api key

You need to set your user api using the following commands:

apikey <- “XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX”

idbr::idb_api_key(apikey)

Step 4. Get data

Using the get_idb() command, you can specify all sorts of queries to get various levels of data complexity. All the variable combinations for the international database are described well here.

Example 1. Life expectancy

Let’s say you wanted to plot a map of the world with the shading of a country related to its average life expectancy at birth. First we get the necessary data:

lex.dat <- idbr::get_idb(

country = “all”,

year = 2022,

variables = c(“name”, “e0”),

geometry = T)

The ensuing lex.dat object looks like this:

Simple feature collection with 6 features and 4 fields

Geometry type: MULTIPOLYGON

Dimension: XY

Bounding box: xmin: -73.41544 ymin: -55.25 xmax: 75.15803 ymax: 42.68825

Geodetic CRS: SOURCECRS

code year name e0 geometry

1 AF 2022 Afghanistan 53.65 MULTIPOLYGON (((61.21082 35…

2 AO 2022 Angola 62.11 MULTIPOLYGON (((16.32653 -5…

3 AL 2022 Albania 79.47 MULTIPOLYGON (((20.59025 41…

4 AE 2022 United Arab Emirates 79.56 MULTIPOLYGON (((51.57952 24…

5 AR 2022 Argentina 78.31 MULTIPOLYGON (((-65.5 -55.2…

6 AM 2022 Armenia 76.13 MULTIPOLYGON (((43.58275 41

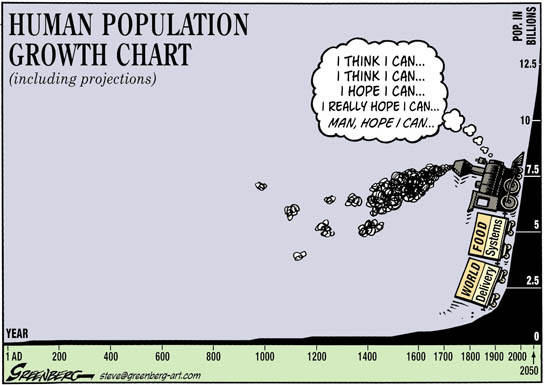

The very worn slur of “neo-Malthusian”

7 09 2021After the rather astounding response to our Ghastly Future paper published in January this year (> 443,000 views and counting; 61 citations and counting), we received a Commentary that was rather critical of our article.

We have finally published a Response to the Commentary, which is now available online (accepted version) in Frontiers in Conservation Science. Given that it is published under a Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY), I can repost the Response here:

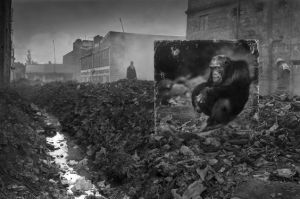

In their comment on our paper Underestimating the challenges of avoiding a ghastly future, Bluwstein et al.2 attempt to contravene our exposé of the enormous challenges facing the entire human population from a rapidly degrading global environment. While we broadly agree with the need for multi-disciplinary solutions, and we worry deeply about the inequality of those who pay the costs of biodiversity loss and ecological collapse, we feel obligated to correct misconceptions and incorrect statements that Bluwstein et al.2 made about our original article.

After incorrectly assuming that our message implied the existence of “one science” and a “united scientific community”, the final paragraph of their comment contradicts their own charge by calling for the scientific community to “… stand in solidarity”. Of course, there is no “one science” — we never made such a claim. Science is by its nature necessarily untidy because it is a bottom-up process driven by different individuals, cultures, perspectives, and goals. But it is solid at the core. Scientific confluence is reached by curiosity, rigorous testing of assumptions, and search for contradictions, leading to many — sometimes counter-intuitive or even conflicting — insights about how the world works. There is no one body of scientific knowledge, even though there is good chance that disagreements are eventually resolved by updated, better evidence, although perhaps too slowly. That was, in fact, a main message of our original article — that obligatory specialisation of disparate scientific fields, embedded within a highly unequal and complex socio-cultural-economic framework, reduces the capacity of society to appreciate, measure, and potentially counter the complexity of its interacting existential challenges. We agree that scientists play a role in political struggles, but we never claimed, as Bluwstein et al.2 contended, that such struggles can be “… reduced to science-led processes of positive change”. Indeed, this is exactly the reason our paper emphasized the political impotence surrounding the required responses. We obviously recognize the essential role social scientists play in creating solutions to avoid a ghastly future. Science can only provide the best available evidence that individuals and policymakers can elect to use to inform their decisions.

We certainly recognise that there is no single policy or polity capable of addressing compounding and mounting problems, and we agree that that there is no “universal understanding of the intertwined socio-ecological challenges we face”. Bluwstein et al.2 claimed that we had suggested scientific messaging alone can “… adequately communicate to the public how socio-ecological crises should be addressed”. We did not state or imply such ideas of unilateral scientific power anywhere in our article. Indeed, the point of framing our message as pertaining to a complex adaptive system means that we cannot, and should not, work towards a single goal. Instead, humanity will be more successful tackling challenges simultaneously and from multiple perspectives, by exploiting manifold institutions, technologies, approaches, and governances to match the complexity of the predicament we are attempting to resolve.

Read the rest of this entry »Share:

Comments : Leave a Comment »

Tags: commentary, complex adaptive system, consumption, critique, human population, Malthusian, neo-Malthusian, over-population, overshoot, Population

Categories : agriculture, anthropocene, biodiversity, climate change, demography, economics, education, Endarkenment, environmental economics, environmental policy, extinction, food, governance, human overpopulation, poverty, science, societies, sustainability