I seem to end up frequently explaining to students and colleagues that it’s a good idea to spend a good deal of time to make your scientific figures the most informative and attractive possible.

But it’s a fine balance between overly flashy and downright boring. Needless to say, empirical accuracy is paramount.

But why should you care, as long as the necessary information is transferred to the reader? The most important answer to that question is that you are trying to catch the attention of editors, reviewers, and readers alike in a highly competitive sea of information. Sure, if the work is good and the paper well-written, you’ll still garner a readership; however, if you give your readers a bit of visual pleasure in the process, they’re much more likely to (a) remember and (b) cite your paper.

I try to ask myself the following when creating a figure — without unnecessary bells and whistles, would I present this figure in a presentation to a group of colleagues? Would I present it to an audience of non-experts? Would I want this figure to appear in a news article about my work? Of course, all of these venues require differing degrees of accuracy, complexity, and aesthetics, but a good figure should ideally serve to educate across very different audiences simultaneously.

A sub-question worth asking here is whether you think a colleague would use your figure in one of their presentations. Think of the last time you made a presentation and found that perfect figure that brilliantly portrays the point you are trying to get across. That’s the kind of figure you should strive to make in your own research papers.

I therefore tend to spend quite a bit of time crafting my figures, and after years of making mistakes and getting a few things right, and retrospectively discovering which figures appear to garner more attention than others, I can offer some basic advice about the DOs and DON’Ts of figure making. Throughout the following section I provide some examples from my own papers that I think demonstrate some of the concepts.

tables vs. graphs — The very first question you should ask yourself is whether you can turn that boring and ugly table into a graph of some sort. Do you really need that table? Can you not just translate the cell entries into a bar/column/xy plot? If you can, you should. When a table cannot easily be translated into a figure, most of the time it probably belongs in the Supplementary Information anyway.

Read the rest of this entry »

I contend that publishing articles in nearly all peer-reviewed journals amounts to a form of

I contend that publishing articles in nearly all peer-reviewed journals amounts to a form of

A modified excerpt from my upcoming book for you to contemplate after your next

A modified excerpt from my upcoming book for you to contemplate after your next

As have many other scientists, I’ve

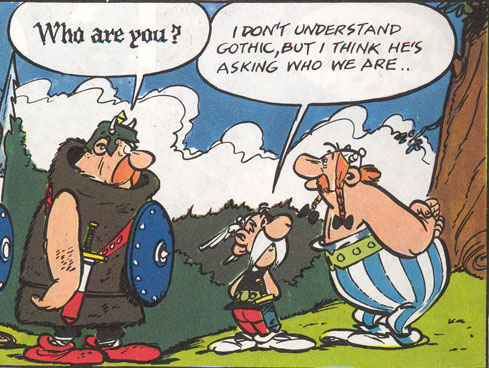

As have many other scientists, I’ve  With all the nasty nationalism and xenophobia gurgling nauseatingly to the surface of our political discourse1 these days, it is probably worth some reflection regarding the role of multiculturalism in science. I’m therefore going to take a stab, despite being in most respects a ‘golden child’ in terms of privilege and opportunity (I am, after all, a middle-aged Caucasian male living in a wealthy country). My cards are on the table.

With all the nasty nationalism and xenophobia gurgling nauseatingly to the surface of our political discourse1 these days, it is probably worth some reflection regarding the role of multiculturalism in science. I’m therefore going to take a stab, despite being in most respects a ‘golden child’ in terms of privilege and opportunity (I am, after all, a middle-aged Caucasian male living in a wealthy country). My cards are on the table.