The Honourable Dr Susan Close MP, Deputy Premier and Minister for Climate, Environment and Water, South Australia

The Honourable Claire Scriven MLC, Minister for Primary Industries and Regional Development, South Australia

Dear Ministers,

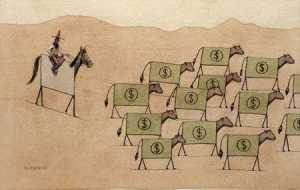

In light of new genetic research on the identity of ‘wild dogs’ and dingoes across Australia, the undersigned wish to express concern with current South Australia Government policy regarding the management and conservation of dingoes. Advanced DNA research on dingoes has demonstrated that dingo-dog hybridisation is much less common than thought, that most DNA tested dingoes had little domestic dog ancestry and that previous DNA testing incorrectly identified many dingoes as hybrids (Cairns et al. 2023). We have serious concerns about the threat current South Australian public policy poses to the survival of the ‘Big Desert’ dingo population found in Ngarkat Conservation Park and surrounding areas.

We urge the South Australian Government to:

- Revoke the requirement that all landholders follow minimum baiting standards, including organic producers or those not experiencing stock predation. Specifically

- Dingoes in Ngarkat Conservation park (Region 4) should not be destroyed or subjected to ground baiting and trapping every 3 months. The Ngarkat dingo population is a unique and isolated lineage of dingo that is threatened by inbreeding and low genetic diversity. Dingoes are a native species and all native species should be protected inside national parks and conservation areas.

- Landholders should not be required to carry out ground baiting on land if there is no livestock predation occurring. Furthermore, landholders should be supported to adopt non-lethal tools and strategies to mitigate the risk of livestock predation including the use of livestock guardian animals, which are generally incompatible with ground and aerial 1080 baiting.

- Revoke permission for aerial baiting of dingoes (incorrectly called “wild dogs”) in all Natural Resource Management regions – including within national parks. Native animals should be protected in national parks and conservation areas.

- Cease the use of inappropriate and misleading language to label dingoes as “wild dogs”. Continued use of the term “wild dogs” is not culturally respectful to First Nations peoples and is not evidence-based.

- Proactively engage with First Nations peoples regarding the management of culturally significant species like dingoes. For example, the Wotjobaluk nation should be included in consultation regarding the management of dingoes in Ngarkat Conservation Park.

Changes in South Australia public policy are justified based on genetic research by Cairns et al. (2023) that overturns previous misconceptions about the genetic status of dingoes. It demonstrates:

- Most “wild dogs” DNA tested in arid and remote parts of Australia were dingoes with no evidence of dog ancestry. There is strong evidence that dingo-dog hybridisation is uncommon, with firstcross dingo-dog hybrids and feral dogs rarely being observed in the wild. In Ngarkat Conservation park none of DNA tested animals had evidence of domestic dog ancestry, all were ‘pure’ dingoes.

- Previous DNA testing methods misidentified pure dingoes as being mixed. All previous genetic surveys of wild dingo populations used a limited 23-marker DNA test. This is the method currently used by NSW Department of Primary Industries, which DNA tests samples from NSW Local Land Services, National Parks and Wildlife Service, and other state government agencies. Comparisons of DNA testing methods find that the 23-marker DNA test frequently misidentified animals as dingo-dog hybrids. Existing knowledge of dingo ancestry across South Australia, particularly from Ngarkat Conservation park is incorrect; policy needs to be based on updated genetic surveys.

- There are multiple dingo populations in Australia. High-density genomic data identified more than four wild dingo populations in Australia. In South Australia there are at least two dingo populations present: West and Big Desert. The West dingo population was observed in northern South Australia, but also extends south of the dingo fence. The Big Desert population extends from Ngarkat Conservation park in South Australia into the Big Desert and Wyperfield region of Victoria.

- The Ngarkat Dingo population is threatened by low genetic variability. Preliminary evidence from high density genomic testing of dingoes in Ngarkat Conservation park and extending into western Victoria found evidence of limited genetic variability which is a serious conservation concern. Dingoes in Ngarkat and western Victoria had extremely low genetic variability and no evidence of gene flow with other dingo populations, demonstrating their effective isolation. This evidence suggests that the Ngarkat (and western Victorian) dingo population is threatened by inbreeding and genetic isolation. Continued culling of the Ngarkat dingo population will exacerbate the low genetic variability and threatens the persistence of this population.

So, a few of us have just submitted a letter contesting the Western Australia Government’s recent decision to delist dingoes as ‘fauna’ (I know — what the hell else could they be?). The letter was organised brilliantly by Dr

So, a few of us have just submitted a letter contesting the Western Australia Government’s recent decision to delist dingoes as ‘fauna’ (I know — what the hell else could they be?). The letter was organised brilliantly by Dr