… properly, or at least ‘better’.

… properly, or at least ‘better’.

In the past I have provided ranked lists of journals in conservation ecology according to their ISI® Impact Factor (see lists for 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012 & 2013). These lists have proven to be exceedingly popular.

Why are journal metrics and the rankings they imply so in-demand? Despite many people loathing the entire concept of citation-based journal metrics, we scientists, our administrators, granting agencies, award committees and promotion panellists use them with such merciless frequency that our academic fates are intimately bound to the ‘quality’ of the journals in which we publish.

Human beings love to rank themselves and others, the things they make, and the institutions to which they belong, so it’s a natural expectation that scientific journals are ranked as well.

I’m certainly not the first to suggest that journal quality cannot be fully captured by some formulation of the number of citations its papers receive; ‘quality’ is an elusive characteristic that includes inter alia things like speed of publication, fairness of the review process, prevalence of gate-keeping, reputation of the editors, writing style, within-discipline reputation, longevity, cost, specialisation, open-access options and even its ‘look’.

It would be impossible to include all of these aspects into a single ‘quality’ metric, although one could conceivably rank journals according to one or several of those features. ‘Reputation’ is perhaps the most quantitative characteristic when measured as citations, so we academics have chosen the lowest-hanging fruit and built our quality-ranking universe around them, for better or worse.

I was never really satisfied with metrics like black-box Impact Factors, so when I started discovering other ways to express the citation performance of the journals to which I regularly submit papers, I became a little more interested in the field of bibliometrics.

In 2014 I wrote a post about what I thought was a fairer way to judge peer-reviewed journal ‘quality’ than the default option of relying solely on ISI® Impact Factors. I was particularly interested in why the new kid on the block — Google Scholar Metrics — gave at times rather wildly different ranks of the journals in which I was interested.

So I came up with a simple mean ranking method to get some idea of the relative citation-based ‘quality’ of these journals.

It was a bit of a laugh, really, but my long-time collaborator, Barry Brook, suggested that I formalise the approach and include a wider array of citation-based metrics in the mean ranks.

Because Barry’s ideas are usually rather good, I followed his advice and together we constructed a more comprehensive, although still decidedly simple, approach to estimate the relative ranks of journals from any selection one would care to cobble together. In this case, however, we also included a rank-placement resampler to estimate the uncertainty associated with each rank.

I’m pleased to announce that the final version1 is now published in PLoS One2. Read the rest of this entry »

A modified excerpt from my upcoming book for you to contemplate after your next

A modified excerpt from my upcoming book for you to contemplate after your next

As have many other scientists, I’ve

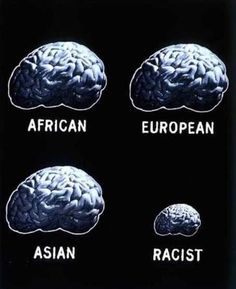

As have many other scientists, I’ve  With all the nasty nationalism and xenophobia gurgling nauseatingly to the surface of our political discourse1 these days, it is probably worth some reflection regarding the role of multiculturalism in science. I’m therefore going to take a stab, despite being in most respects a ‘golden child’ in terms of privilege and opportunity (I am, after all, a middle-aged Caucasian male living in a wealthy country). My cards are on the table.

With all the nasty nationalism and xenophobia gurgling nauseatingly to the surface of our political discourse1 these days, it is probably worth some reflection regarding the role of multiculturalism in science. I’m therefore going to take a stab, despite being in most respects a ‘golden child’ in terms of privilege and opportunity (I am, after all, a middle-aged Caucasian male living in a wealthy country). My cards are on the table. We scientists can unfortunately be real bastards to each other, and no other interaction brings out that tendency more than peer review. Of course no one, no matter how experienced, likes to have a manuscript rejected. People hate to be on the receiving end of any criticism, and scientists are certainly no different. Many reviews can be harsh and unfair; many reviewers ‘miss the point’ or are just plain nasty.

We scientists can unfortunately be real bastards to each other, and no other interaction brings out that tendency more than peer review. Of course no one, no matter how experienced, likes to have a manuscript rejected. People hate to be on the receiving end of any criticism, and scientists are certainly no different. Many reviews can be harsh and unfair; many reviewers ‘miss the point’ or are just plain nasty.