We’ve got a real treat for biodiversity buffs scheduled for the end of March. Eminent (Distinguished, Famous, Respected… the list goes on) Professor William (Bill) Laurance is briefly leaving his tropical world and coming south to the temperate climes of Adelaide to regale us with his fascinating biodiversity research career.

Bill is a leading conservation biologist who has worked internationally on many high-profile threats to tropical forests—in the Amazon, Central America, Africa, and Australasia. A highly prolific scientist, to date he has published five books and over 300 scientific articles. Bill has recently commenced a position as Distinguished Research Professor at James Cook University and is involved with the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute in Panama. He also happens to be the bloke that blew the lid open on the devastating effects of tropical fragmentation in the Amazon with some of the best long-term experiments ever done in conservation biology.

I’m personally very pleased for several reasons: (1) Although I have never met Bill in person yet, I’ve recently co-authored two papers with him (Wash and spin cycle threats to tropical biodiversity and Improving the performance of the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil for nature conservation) and I’m keen to meet the man behind the pen; (2) we have had many email discussions (some of them rather heated!), so I’m keen to flesh some of these out over a nice glass of South Australian Shiraz; (3) he’s been a keen supporter of my work for years, and has given me many opportunities to get my research noticed; and (4) it’s high time to met one of ConservationBytes.com Conservation Scholars.

Bill has recently shifted shop from Panama (Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute) to Australia’s own James Cook University, and so we at the Environment Institute thought we should take advantage of his geographical disorientation and bring him down south for a while. But he’s going to have to sing for his supper, so he’s kindly agreed to give three talks in 3 days from 29-31 March 2010.

His first talk (on Monday 29 March) will be an in-house Environment Institute seminar, but the second two will be public events that I urge anyone remotely interested in biodiversity conservation research to attend. In fact, his Tuesday 30 March presentation (18.00-20.00 Napier G03, University of Adelaide) is even more generic than that, and word on the street is it is highly entertaining and extremely well attended wherever Bill’s is gracious enough to give it:

Amplify Your Voice: Keys to Having a Prolific Scientific Career (and Bill would know).

This will include (1) How to be more prolific: strategies for writing and publishing scientific papers and (2) Further ways to maximise your scientific impact – interacting with the popular media and how to promote yourself. Each topic will run for 50 minutes and will include 10 minutes for audience questions. A tea and coffee break will be held between sessions. Book here.

This will include (1) How to be more prolific: strategies for writing and publishing scientific papers and (2) Further ways to maximise your scientific impact – interacting with the popular media and how to promote yourself. Each topic will run for 50 minutes and will include 10 minutes for audience questions. A tea and coffee break will be held between sessions. Book here.

His second public talk on Wednesday 31 March (18.00-19.30 Napier 102, University of Adelaide) will be:

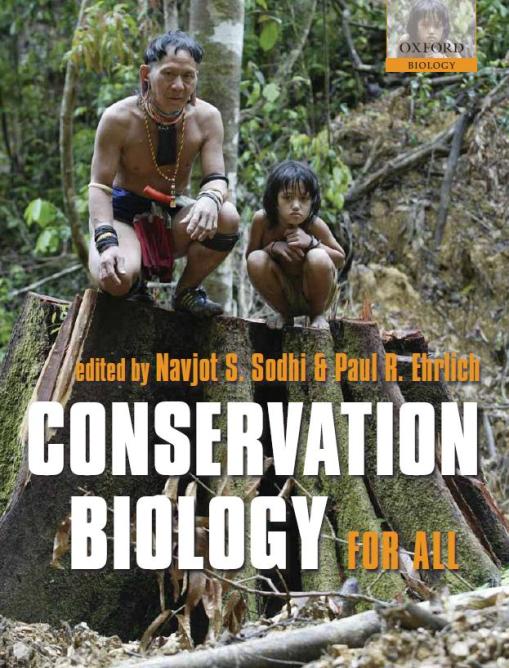

Diagnosis Critical | The lungs of our Planet

Here he will be discussing how the forests of our world are in crisis. Our drive for continued economic growth has had devastating consequences for the world’s ecosystems that provide critical human services. Our forests are a haven for countless plant and animal species that form the basis of ecological services, these services are the biological mechanisms that make the world our home. Book here.

So, if you have a couple of free nights at the end of the month and are in Adelaide, I strongly recommend you come out and see Bill do his thing.

Today’s post covers a neat little review just published online in

Today’s post covers a neat little review just published online in

“…nobody puts a value on pollination; national accounts do not reflect the value of ecosystem services that stop soil erosion or provide watershed protection.“

“…nobody puts a value on pollination; national accounts do not reflect the value of ecosystem services that stop soil erosion or provide watershed protection.“