Last year our group published a paper in Journal of Ecology that examined, for the first time, the life history correlates of a species’ likelihood to become invasive or threatened.

Last year our group published a paper in Journal of Ecology that examined, for the first time, the life history correlates of a species’ likelihood to become invasive or threatened.

The paper is entitled Threat or invasive status in legumes is related to opposite extremes of the same ecological and life-history attributes and was highlighted by the Editor of the journal.

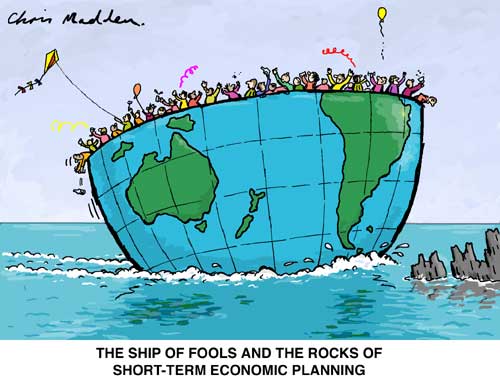

The urgency and scale of the global biodiversity crisis requires being able to predict a species’ likelihood of going extinct or becoming invasive. Why? Well, without good predictive tools about a species’ fate, we can’t really prepare for conservation actions (in the case of species more likely to go extinct) or eradication (in the case of vigorous invasive species).

We considered the problem of threat and invasiveness in unison based on analysis of one of the largest-ever databases (8906 species) compiled for a single plant family (Fabaceae = Leguminosae). We chose this family because it is one of the most speciose (i.e., third highest number of species) in the Plant kingdom, its found throughout all continents and terrestrial biomes except Antarctica, its species range in size from dwarf herbs to large tropical trees, and its life history, form and functional diversity makes it one of the most important plant groups for humans in terms of food production, fodder, medicines, timber and other commercial products. Choosing only one family within which to examine cross-species trends also makes the problem of shared evolutionary histories less problematic from the perspective of confounded correlations.

We found that tall, annual, range-restricted species with tree-like growth forms, inhabiting closed-forest and lowland sites are more likely to be threatened. Conversely, climbing and herbaceous species that naturally span multiple floristic kingdoms and habitat types are more likely to become invasive.

Our results support the idea that species’ life history and ecological traits correlate with a fate response to anthropogenic global change. In other words, species do demonstrate particular susceptibility to either fate based on their evolved traits, and that traits generally correlated with invasiveness are also those that correlate with a reduced probability of becoming threatened.

Conservation managers can therefore benefit from these insights by being able to rank certain plant species according to their risk of becoming threatened. When land-use changes are imminent, poorly documented species can essentially be ranked according to those traits that predispose them to respond negatively to habitat modification. Here, species inventories combined with known or expected life history information (e.g., from related species) can identify which species may require particular conservation attention. The same approach can be used to rank introduced plant species for their probability of spreading beyond the point of introduction and threatening native ecosystems, and to prioritise management interventions.

I hope more taxa are examined with such scrutiny so that we can have ready-to-go formulae for predicting a wider array of potential fates.

I’m recommending you view a video presentation (can be accessed by clicking the link below) by A/Prof. David Paton which demonstrates the urgency of reforesting the region around Adelaide. Glenthorne is a 208-ha property 17 km south of the Adelaide’s central business district owned and operated by the

I’m recommending you view a video presentation (can be accessed by clicking the link below) by A/Prof. David Paton which demonstrates the urgency of reforesting the region around Adelaide. Glenthorne is a 208-ha property 17 km south of the Adelaide’s central business district owned and operated by the