I’m in the field at the moment, so here are the latest six cartoons to pass the time (see full stock of previous ‘Cartoon guide to biodiversity loss’ compendia here). Enjoy.

—

I’m in the field at the moment, so here are the latest six cartoons to pass the time (see full stock of previous ‘Cartoon guide to biodiversity loss’ compendia here). Enjoy.

—

I’ve always barracked for Peter Kareiva‘s views and work; I particularly enjoy his no-bullshit, take-no-prisoners approach to conservation. Sure, he’s said some fairly radical things over the years, and has pissed off more than one conservationist in the process. But I think this is a good thing.

I’ve always barracked for Peter Kareiva‘s views and work; I particularly enjoy his no-bullshit, take-no-prisoners approach to conservation. Sure, he’s said some fairly radical things over the years, and has pissed off more than one conservationist in the process. But I think this is a good thing.

His main point (as is mine, and that of a growing number of conservation scientists) is that we’ve already failed biodiversity, so it’s time to move into the next phase of disaster mitigation. By ‘failing’ I mean that, love it or loathe it, extinction rates are higher now than they have been for millennia, and we have very little to blame but ourselves. Apart from killing 9 out of 10 people on the planet (something no war or disease will ever be able to do), we’re stuck with the rude realism that it’s going to get a lot worse before it gets better.

This post acts mostly an introduction to Peter Kareiva & collaborators’ latest essay on the future of conservation science published in the Breakthrough Institute‘s new journal. While I cannot say I agree with all components (especially the cherry-picked resilience examples), I fundamentally support the central tenet that we have to move on with a new state of play.

In other words, humans aren’t going to go away, ‘pristine’ is as unattainable as ‘infinity’, and reserves alone just aren’t going to cut it. Read the rest of this entry »

The last post of 2011, I thought I’d focus on the lighter side (that is to say, my brain is muddled by the lovely break from academia, so I don’t really feel like investing too much cerebral energy). Here, therefore, are the latest six cartoons… (see full stock of previous ‘Cartoon guide to biodiversity loss’ compendia here). May fewer species go extinct in 2012 than 2011…

—

In April this year, some American colleagues of ours wrote a rather detailed, 10-page article in Trends in Ecology and Evolution that attacked our concept of generalizing minimum viable population (MVP) size estimates among species. Steve Beissinger of the University of California at Berkeley, one of the paper’s co-authors, has been a particularly vocal adversary of some of the applications of population viability analysis and its child, MVP size, for many years. While there was some interesting points raised in their review, their arguments largely lacked any real punch, and they essentially ended up agreeing with us.

In April this year, some American colleagues of ours wrote a rather detailed, 10-page article in Trends in Ecology and Evolution that attacked our concept of generalizing minimum viable population (MVP) size estimates among species. Steve Beissinger of the University of California at Berkeley, one of the paper’s co-authors, has been a particularly vocal adversary of some of the applications of population viability analysis and its child, MVP size, for many years. While there was some interesting points raised in their review, their arguments largely lacked any real punch, and they essentially ended up agreeing with us.

Let me explain. Today, our response to that critique was published online in the same journal: Minimum viable population size: not magic, but necessary. I want to take some time here to summarise the main points of contention and our rebuttal.

But first, let’s recap what we have been arguing all along in several papers over the last few years (i.e., Brook et al. 2006; Traill et al. 2007, 2010; Clements et al. 2011) – a minimum viable population size is the point at which a declining population becomes a small population (sensu Caughley 1994). In other words, it’s the point at which a population becomes susceptible to random (stochastic) events that wouldn’t otherwise matter for a small population.

Consider the great auk (Pinguinus impennis), a formerly widespread and abundant North Atlantic species that was reduced by intensive hunting throughout its range. How did it eventually go extinct? The last remaining population blew up in a volcanic explosion off the coast of Iceland (Halliday 1978). Had the population been large, the small dent in the population due to the loss of those individuals would have been irrelevant.

But what is ‘large’? The empirical evidence, as we’ve pointed out time and time again, is that large = thousands, not hundreds, of individuals.

So this is why we advocate that conservation targets should aim to keep at or recover to the thousands mark. Less than that, and you’re playing Russian roulette with a species’ existence. Read the rest of this entry »

While I can’t claim that this is the first time one of my peer-reviewed papers has been inspired by ConservationBytes.com, I can claim that this is the first time a peer-reviewed paper is derived from the blog.

While I can’t claim that this is the first time one of my peer-reviewed papers has been inspired by ConservationBytes.com, I can claim that this is the first time a peer-reviewed paper is derived from the blog.

After a bit of a sordid history of review (isn’t it more and more like that these days?), I have the pleasure of announcing that our paper ‘Twenty landmark papers in biodiversity conservation‘ has now been published as an open-access chapter in the new book ‘Research in Biodiversity – Models and Applications‘ (InTech).

Perhaps not the most conventional of venues (at least, not for me), but it is at the very least ‘out there’ now and freely available.

The paper itself was taken, modified, elaborated and over-hauled from text written in this very blog – the ‘Classics‘ section of ConservationBytes.com. Now, if you’re an avid follower of CB, then the chapter won’t probably represent anything terribly new; however, I encourage you to read it anyway given that it is a vetted overview of possibly some of the most important papers written in conservation biology.

If you are new to the field, an active student or merely need a ‘refresher’ regarding the big leaps forward in this discipline, then this chapter is for you.

The paper’s outline is as follows: Read the rest of this entry »

Another corker from Salvador Herrando-Pérez:

Another corker from Salvador Herrando-Pérez:

—

Cinema fans know that choosing a movie by the newspaper’s commentary or the promotional poster might be a lottery. In the movie of nature, to confuse ‘the attractive’ with ‘the appropriate’ can compromise the life of an individual and its offspring, even to the extent of anticipating the extinction of an entire population or species.

Animals make daily choices about when, where or with whom to engage in basic activities like eating, hibernating, mating, migrating or resting. Those choices are often strongly tied to highly specific cues – e.g., air temperature, tree density, location of water, or smell of other individuals. And it happens to hair lice jumping from head to head among school kids, or to caribou forming their winter herds prior to the seasonal migration. All species, without exception, persist in nature because those ‘choices’ translate into survival or successful reproduction more often than do not. They are a kind of evolutionary memory imprinted in an organism’s genes and behaviour. However, sometimes the right choice (‘right’ meaning perceiving a cue for the role it actually has in the life cycle) places an individual in the worst of all possible situations. The environment cheats, ‘the attractive’ merely mimics ‘the appropriate’, and the individual fails to reproduce, starves, sickens, or even dies.

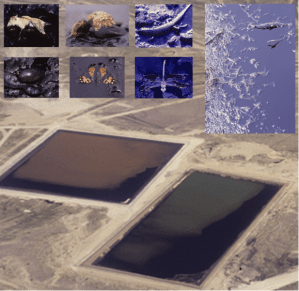

Figure 1. Water reservoirs tainted with fuel (see dark contours) in Kuwait following the Gulf War in the early 1990s. Overlaid pictures show the silhouettes of trapped odonates (right), vertebrates (top left) and invertebrates (bottom left) (Photos courtesy of Jochen Zeil).

At the mercy of mirages

During the Gulf War, the destruction of infrastructure for crude exploitation spilled large amounts of fuel in many water reservoirs over the desert landscape of Kuwait. A little later, Horváth and Zeil1 found agglomerations of dead insects (and a range of vertebrates) along the shores of these polluted reservoirs, and observed dragonflies drowning in their kamikaze attempt to spawn on the oily surface (Figure 1). This work stimulated further research whereby Horváth and his team in Budapest showed that odonates are attracted by light polarization at the surface of oiled water2 – hence ‘polarized light pollution’3. Not only that, they recorded insects struggling to spawn on or mate with riveting surfaces such as solar panels, asphalted roads, plastic bags or (creepy enough!) cemetery crypts4. It goes without saying: these insects are victims of a mirage.

Those habitats or features of the habitat that mislead an animal’s choice, often hampering the completion of its life cycle, are known as ‘ecological traps’ – in other words, the environmental cue is decoupled from the quality of the habitat it is meant to signal. Ecological traps were first described in the 1970s by Dwernychuk and Boag5. They found that ducks on the islands of Miquelon lake located their nests among those of seagulls despite the latter happily devoured their ducklings and eggs. When these islands emerged in the middle of last century, they were first colonized by common terns (Sterna hirundo). By defending their own nests ferociously from predators (mainly crows and magpies), the terns inadvertently shielded the nests of their ducky comrades. The Canadians hypothesized that when seagulls subsequently replace terns, the ducks continued to sense their new neighbours as a (now misleading) sign of protection. Read the rest of this entry »

Last week, The Conversation published a particularly wonderful example of uninformed drivel that requires a little bit of a reality injection.

Like our good friend, the Destroyer of Forests (a.k.a. Alan Oxley), a new pro-deforestation, pro-development cheerleader on the scene, a certain Phillip Lawrence apparently undertaking a PhD entitled ‘Ecological Modernization of the Indonesian Economy: A Political, Cultural and Historical Economic Study‘ at Macquarie University in Sydney (The Conversation mistakenly attributes him to the University of Sydney, unless of course, he’s moved recently), has royally stuck his foot in it with respect to the dangers of oil palm in South-East Asia.

Mr. Lawrence runs an interestingly titled blog ‘Eco Logical Strategies‘, especially considering there is nothing whatsoever regarding ‘ecology’ on the site, and this ignorance comes forth in a wonderful array of verbal spew in his latest Conversation piece. He’s also a consultant for one of the most destructive forces in Indonesia – Asia Pulp and Paper – a company with a more depressive environmental track record than the likes of Monsanto, General Electric and BP combined. That preface of conflict of interest now explained, I will now expose Mr. Lawrence for the wolf in sheep’s clothing he really is.

Banging the development and anti-poverty drum like Oxley, albeit with much less panache and linguistic flourish, Mr. Lawrence boldly claims, without a shred of evidence, that “There is ample peer-reviewed research that is supportive of the palm oil industry in Indonesia.”

Excuse me? Supportive of just what component of the palm oil industry, Mr. Lawrence? Would that be that it makes a shit-load of cash for a preciously small component of Indonesian (and foreign) society? Let’s just look at the peer-reviewed literature, shall we? Read the rest of this entry »

Is oil palm bad? Is protecting tropical forests more important than converting them for economic development? Should we spike trees to make sure no one cuts them down?

Is oil palm bad? Is protecting tropical forests more important than converting them for economic development? Should we spike trees to make sure no one cuts them down?

Answers to these questions depend on which side of the argument you’re on. But often people on either side of debates hardly know what their opponents are thinking.

A recent paper by us in the journal Biotropica, of which parts were published on this blog, points out that the inability to recognise differing viewpoints undermines progress in environmental policy and practice.

The paper in Biotropica takes an unusual approach to get its message across, one rarely applied in science, but nevertheless dating back to 1729. In that year, Jonathan Swift, the first satirist, wrote an essay suggesting the English should eat Irish children, “whether stewed, roasted, baked, or boiled”, to reduce the growing population of Irish poor.

We similarly use satire to highlight the viewpoint problem. Our paper uses a spoof press release by the Coalition of Financially Challenged Countries with Lots of Trees, aka “CoFCCLoT”. CoFCCLoT proposes that in return for nor cutting down their tropical rainforests, wealthy countries should reforest at least half their land. This would provide the world with a level playing field, restore the ecological health of wealthy countries, provide job opportunities for their citizens, and even allow lions to thrive in Greece and gorillas in Spain. Read the rest of this entry »

The latest six cartoons… (see full stock of previous ‘Cartoon guide to biodiversity loss’ compendia here).

—

A few weeks back I cosigned a ‘statement of concern’ about the proposal for Australia’s South West Marine Region organised by Hugh Possingham. The support has been overwhelming by Australia’s marine science community (see list of supporting scientists below). I’ve reproduced the letter addressed to the Australian government – distribute far and wide if you give more than a shit about the state of our marine environment (and the economies it supports). Basically, the proposed parks are merely a settlement between government and industry where nothing of importance is really being protected. The parks are just the leftovers industry doesn’t want. No way to ensure the long-term viability of our seas.

—

On 5 May 2011 the Australian Government released a draft proposal for a network of marine reserves in the Commonwealth waters of the South West bioregional marine planning region.

Australia’s South West is of global significance for marine life because it is a temperate region with an exceptionally high proportion of endemic species – species found nowhere else in the world.

Important industries, such as tourism and fisheries, depend on healthy marine ecosystems and the services they provide. Networks of protected areas, with large fully protected core zones, are essential to maintain healthy ecosystems over the long-term – complemented by responsible fisheries management1.

The selection and establishment of marine reserves should rest on a strong scientific foundation. We are greatly concerned that what is currently proposed in the Draft South West Plan is not based on the three core science principles of reserve network design: comprehensiveness, adequacy and representation. These principles have been adopted by Australia for establishing our National Reserve System and are recognized internationally2.

Specifically, the draft plan fails on the most basic test of protecting a representative selection of habitats within the bioregions of the south-west. There are no highly protected areas proposed at all in three of the seven marine bioregions lying on the continental shelf3. Overall less than 3.5% of the shelf, where resource use and biodiversity values are most intense, is highly protected. Further, six of the seven highly protected areas that are proposed on the shelf are small (< 20 km in width)4 and all are separated by large distances (> 200 km)5. The ability of such small isolated areas to maintain connectivity and fulfil the goal of protecting Australia’s marine biodiversity is limited. Read the rest of this entry »

Another fine contribution from Salvador Herrando-Pérez (see previous posts here, here, here and here).

—

Sometimes evolution fails to shape new species that are able to expand the habitat of their ancestors. This failure does not rein in speciation, but forces it to take place in a habitat that changes little over geological time. Such evolutionary outcomes are important to predict the distribution of groups of phylogenetically related species.

Sometimes evolution fails to shape new species that are able to expand the habitat of their ancestors. This failure does not rein in speciation, but forces it to take place in a habitat that changes little over geological time. Such evolutionary outcomes are important to predict the distribution of groups of phylogenetically related species.

Those who have ever written a novel, a biography, or even a court application, will know that a termite-eaten photo or an old hand-written letter can help rebuild moments of our lives with surgical precision. Likewise, museums of natural sciences store historical biodiversity data of great value for modern research and conservation1.

A notable example is the study of chameleons from Madagascar by Chris Raxworthy and colleagues2. By collating 621 records of 11 species of the tongue-throwing reptiles, these authors subsequently concentrated survey efforts on particular regions where they discovered the impressive figure of seven new species to science, which has continued to expand3 (see figure below). The trick was to characterise the habitat at historical and modern chameleon records on the basis of satellite data describing climate, hydrology, topography, soil and vegetation, then extrapolate over the entire island to predict what land features were most likely to harbour other populations and species. This application of species distribution models4 supports the idea that the phenotypic, morphological and ecological shifts brought about by speciation can take place at slower rates than changes in the habitats where species evolve – the so-called ‘niche conservatism’ (a young concept with already contrasting definitions, e.g.,5-7).

Last week I came across a report that 60 % of economists support the newly proposed Australian carbon tax initiative, and that most believed the Coalition’s plan was inferior and would likely be more costly.

I thought that it would be good to survey ecologists on this very same issue because we are the people dealing with the fall-out of climate change to natural systems, and we are the group communicating it and its consequences to the greater public. Climate change effects on the Australian biota are already being witnessed, and if we don’t take the lead in this over-populated world of myopic, self-interested growth addicts, it’s our children who will suffer most.

Usually, ecologists and economists tend to disagree on major policies because of the general view that development is incompatible with functioning ecosystems; however in this case, it’s telling that the two seem to agree. If economists and ecologists together support something, it’s probably a good idea to give it a go. Read the rest of this entry »

Today on The Conversation, it was reported that 60 % of 145 economists surveyed support Australia’s new Carbon Tax scheme.

Today on The Conversation, it was reported that 60 % of 145 economists surveyed support Australia’s new Carbon Tax scheme.

I am wondering what kind of support there is for it out there amongst ecologists. If you are one, please complete the following short survey by clicking here.

I’ll post the results in a few days.

A couple of weeks ago we (Andy Lowe and I) did a small interview on ABC television about the current status of Australia forests, followed by a discussion regarding our recently funded Australian Research Council Linkage Project Developing best-practice approaches for restoring forest ecosystems that are resilient to climate change. Just in case you didn’t see it, I’ve managed to upload a copy of the piece to Youtube.com and reproduce it here:

I’m actually in the process of writing a paper on all this for a special issue of Journal of Plant Ecology (that is nearly already overdue!), but here are a few facts for you in the interim:

I’m sitting in the Brisbane airport contemplating how best to describe the last week. If you’ve been following my tweets, you’ll know that I’ve been sequestered in a room with 8 other academics trying to figure out the best ways to estimate the severity of the Anthropocene extinction crisis. Seems like a pretty straight forward task. We know biodiversity in general isn’t doing so well thanks to the 7 billion Homo sapiens on the planet (hence, the Anthropo prefix) – the question though is: how bad?

I blogged back in March that a group of us were awarded a fully funded series of workshops to address that question by the Australian Centre for Ecological Synthesis and Analysis (a Terrestrial Ecosystem Research Network facility based at the University of Queensland), and so I am essentially updating you on the progress of the first workshop.

Before I summarise our achievements (and achieve, we did), I just want to describe the venue. Instead of our standard, boring, windowless room in some non-descript building on campus, ACEAS Director, Associate Professor Alison Specht, had the brilliant idea of putting us out away from it all on a beautiful nature-conservation estate on the north coast of New South Wales.

What a beautiful place – Linneaus Estate is a 111-ha property just a few kilometres north of Lennox Head (about 30 minutes by car south of Byron Bay) whose mission is to provide a sustainable living area (for a very lucky few) while protecting and restoring some pretty amazing coastal habitat along an otherwise well-developed bit of Australian coastline. And yes, it’s named after Carl Linnaeus. Read the rest of this entry »

It’s been another year of citations and now the latest list of ISI Impact Factors (2010) has come out. Regardless of how much stock you put in these (see here for a damning review), you cannot ignore their influence on publishing trends and author journal choices.

It’s been another year of citations and now the latest list of ISI Impact Factors (2010) has come out. Regardless of how much stock you put in these (see here for a damning review), you cannot ignore their influence on publishing trends and author journal choices.

As I’ve done for 2008 and 2009, I’ve taken the liberty of providing the new IFs for some prominent conservation and ecology journals, and a few other journals occasionally publishing conservation-related material.

One particular journal deserves special attention here. Many of you might know that I was Senior Editor with Conservation Letters from 2008-2010, and I (with other editorial staff) made some predictions about where the journal’s first impact factor might be on the scale (see also here). Well, I have to say the result exceeded my expectations (although Hugh Possingham was closer to the truth in the end – bugger!). So the journal’s first 2010 impact factor (for which I take a modicum of credit ;-) is a whopping… 4.694 (3rd among all ‘conservation’ journals). Well done to all and sundry who have edited and published in the journal. My best wishes to the team that has to deal with the inevitable rush of submissions this will likely bring!

So here are the rest of the 2010 Impact Factors with the 2009 values for comparison: Read the rest of this entry »

Read the rest of this entry »

The Coalition of Financially Challenged Countries with Lots of Trees, known as ‘CoFCCLoT’, representing most of the world’s remaining tropical forests, is asking wealthy nations to share global responsibilities and reforest their land for the common good of stabilizing climate and protecting biodiversity.

“We are willing to play our part, but we require a level playing field in which we all commit to equal sacrifices,” a coalition spokeswoman says. “Returning forest cover in the G8 countries and the European Union back to historic coverage will benefit all of us in the long-term.”

Seventy-five per cent of Europe was once forested. Now it is 45 per cent. Some countries such as Ireland saw forest cover reduced to near zero. Most forest cover in the developed world is now often planted with stands of alien trees, turning them into deserts for biodiversity. Remaining natural forests are often highly fragmented and have few native species. Read the rest of this entry »

You’d have to have been living under a rock for the last two weeks not to know that our esteemed colleague, great mate and all-round poker-in-the-eyes-of-convention, Professor Navjot Sodhi, died tragically on 12 June 2011 of lymphoma. but just in case you were under a rock, you can read about it here.

In the weeks that have elapsed, several amazing things have happened – despite Navjot being a complete bastard (note: I use this term in the Australian parlance meaning ‘one who could hold his own, who could detect bullshit at 100 m, who was a wonderful mate, and an even more terrible enemy’ – in essence, the highest compliment and expression of platonic love a man can give to another), his army of students, colleagues, admirers and distant relatives have flown into action to make damn sure he is not forgotten.

First, the outpouring of grief and accolades in the blogosphere hit a pick the week following his death (see here, here and here for examples). There was even a Facebook tribute page established within days. It just so happened too that he died during the Association for Tropical Biology and Conservation‘s annual meeting in Arusha, Tanzania (and with whom Navjot was a council member). I have heard from the likes of Bill Laurance, Luke Gibson, Nigel Stork and others that the meeting ended up essentially being in honour of Navjot once everyone heard the dreadful news. Read the rest of this entry »

My friend and colleague at the Centre National de Recherche Scientfique (CNRS), Laboratoire d’Ecologie Systématique & Evolution based at the Université Paris-Sud in France, Dr. Franck ‘Allee Effect‘ Courchamp, has asked me to help him out finding a suitable candidate for what sounds like a very cool job. If you’re in the market for a very interesting and highly relevant conservation post-doctoral fellowship, please read on.

And even if you’re not looking for a position, but are interested in the anthropogenic Allee effect, then by all means, please read on as well.

—

This two-year fellowship is part of a grant focused on demonstrating the novel rarity paradox, either in new wildlife trade markets (i.e., exotic pets, traditional medicine, et cetera) or in newly exploited species (e.g., tibetan antilope, seahorses, et cetera). Read the rest of this entry »