© J. F. Jaramillo

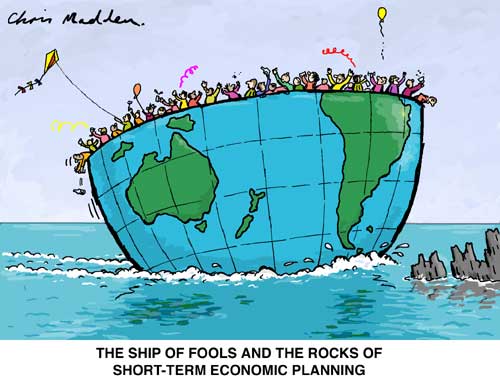

I couldn’t have invented a better example of a Toothless conservation concept.

—

I just saw an article in the Independent (UK) about cloning for conservation that has rehashed the old idea yet again – while there was some interesting thoughts discussed, let’s just be clear just how stupidly inappropriate and wasteful the mere concept of cloning for biodiversity conservation really is.

1. Never mind the incredible inefficiency, the lack of success to date and the welfare issues of bringing something into existence only to suffer a short and likely painful life, the principal reason we should not even consider the technology from a conservation perspective (I have no problem considering it for other uses if developed responsibly) is that you are not addressing the real problem – mainly, the reason for extinction/endangerment in the first place. Even if you could address all the other problems (see below), if you’ve got no place to put these new individuals, the effort and money expended is an utter waste of time and money. Habitat loss is THE principal driver of extinction and endangerment. If we don’t stop and reverse this now, all other avenues are effectively closed. Cloning won’t create new forests or coral reefs, for example.

I may as well stop here, because all other arguments are minor in comparison to (1), but let’s continue just to show how many different layers of stupidity envelop this issue.

2. The loss of genetic diversity leading to inbreeding depression is a major issue that cloning cannot even begin to address. Without sufficient genetic variability, a population is almost certainly more susceptible to disease, reductions in fitness, weather extremes and over-exploitation. A paper published a few years ago by Spielman and colleagues (Most species are not driven to extinction before genetic factors impact them) showed convincingly that genetic diversity is lower in threatened than in comparable non-threatened species, and there is growing evidence on how serious Allee effects are in determining extinction risk. Populations need to number in the 1000s of genetically distinct individuals to have any chance of persisting. To postulate, even for a moment, that cloning can artificially recreate genetic diversity essential for population persistence is stupidly arrogant and irresponsible.

3. The cost. Cloning is an incredibly costly business – upwards of several millions of dollars for a single animal (see example here). Like the costs associated with most captive breeding programmes, this is a ridiculous waste of finite funds (all in the name of fabricated ‘conservation’). Think of what we could do with that money for real conservation and restoration efforts (buying conservation easements, securing rain forest property, habitat restoration, etc.). Even if we get the costs down over time, cloning will ALWAYS be more expensive than the equivalent investment in habitat restoration and protection. It’s wasteful and irresponsible to consider it otherwise.

So, if you ever read another painfully naïve article about the pros and cons of cloning endangered species, remember the above three points. I’m appalled that this continues to be taken seriously!