A little over five years ago, a controversial and spectacularly erroneous paper appeared in the tropical ecology journal Biotropica, the flagship journal of the Association for Tropical Biology and Conservation. Now, I’m normally a fan of Biotropica (I have both published there several times and acted as a Subject Editor for several years), but we couldn’t let that paper’s conclusions go unchallenged.

That paper was ‘The future of tropical forest species‘ by Joseph Wright and Helene Muller-Landau, which essentially concluded that the severe deforestation and degradation of tropical forests was not as big a deal as nearly all the rest of the conservation biology community had concluded (remind you of climate change at all?), and that regenerating, degraded and secondary forests would suffice to preserve the enormity and majority of dependent tropical biodiversity.

What rubbish.

Our response, and those of many others (including from Toby Gardner and colleagues and William Laurance), were fast and furious, essentially destroying the argument so utterly that I think most people merely moved on. We know for a fact that tropical biodiversity is waning rapidly, and in many parts of the world, it is absolutely [insert expletive here]. However, the argument has reared its ugly head again and again over the intervening years, so it’s high time we bury this particular nonsense once and for all.

In fact, a few anecdotes are worthy of mention here. Navjot once told me one story about the time when both he and Wright were invited to the same symposium around the time of the initial dust-up in Biotropica. Being Navjot, he tore off strips from Wright in public for his outrageous and unsubstantiated claims – something to which Wright didn’t take too kindly. On the way home, the two shared the same flight, and apparently Wright refused to acknowledge Navjot’s existence and only glared looks that could kill (hang on – maybe that had something to do with Navjot’s recent and untimely death? Who knows?). Similar public stoushes have been chronicled between Wright and Bill Laurance.

Back to the story. I recall a particular coffee discussion at the National University of Singapore between Navjot Sodhi (may his legacy endure), Barry Brook and me some time later where we planned the idea of a large meta-analysis to compare degraded and ‘primary’ (not overly disturbed) forests. The ideas were fairly fuzzy back then, but Navjot didn’t drop the ball for a moment. He immediately went out and got Tien Ming Lee and his new PhD student, Luke Gibson, to start compiling the necessary studies. It was a thankless job that took several years.

However, the fruits of that labour have now just been published in Nature: ‘Primary forests are irreplaceable for sustaining tropical biodiversity‘, led by Luke and Tien Ming, along with Lian Pin Koh, Barry Brook, Toby Gardner, Jos Barlow, Carlos Peres, me, Bill Laurance, Tom Lovejoy and of course, Navjot Sodhi [side note: Navjot died during the review and didn’t survive to hear the good news that the paper was finally accepted].

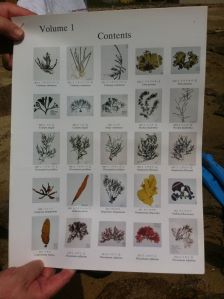

Using data from 138 studies from Asia, South America and Africa comprising 2220 pair-wise comparisons of biodiversity ‘values’ between forests that had undergone some sort of disturbance (everything from selective logging through to regenerating pasture) and adjacent primary forests, we can now hammer the final nails into the coffin containing the putrid remains of Wright and Muller-Landau’s assertion – there is no substitute for primary forest. Read the rest of this entry »

-34.917731

138.603034

This last post before Easter is something I’ve thought more and more about over the last few years. I wouldn’t have given it much time in the past, but I’m now convinced roads are one of the humanity’s most destructive devices. Let me explain.

This last post before Easter is something I’ve thought more and more about over the last few years. I wouldn’t have given it much time in the past, but I’m now convinced roads are one of the humanity’s most destructive devices. Let me explain.