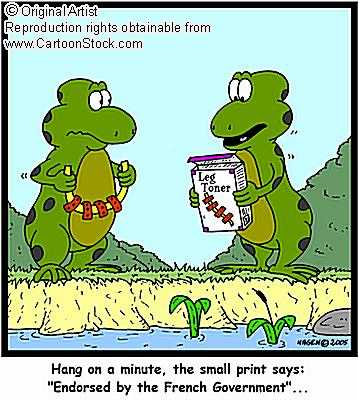

Short story – don’t eat any more frogs’ legs (you probably won’t be missing much).

Why we shouldn’t eat frogs’ legs

In the cavernous community hall of the Vosges spa town of Vittel, a large and lugubrious man, his small, surprisingly chirpy wife, and 450 other people are sitting down to their evening meal. It’s rather noisy. “Dunno why we do it, really,” shouts the man, whose name is Jacky. “Don’t taste of anything, do they? White. Insipid. If it wasn’t for the sauce it’d be like eating some soft sort of rubber. Just the kind of food an Englishman should like, in fact. Hah.”

Outside, the streets are filled with revellers. A funfair is going full swing. The restaurants along the high street are full, and queues have formed before the stands run by the local football, tennis, basketball, rugby and youth clubs.

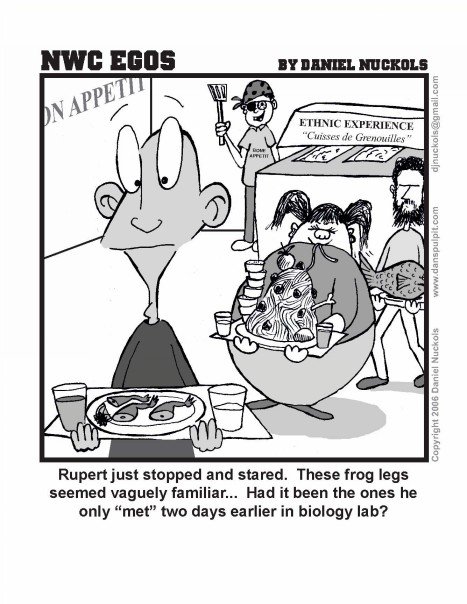

All offer the same thing: cuisses de grenouilles à la provencale (with garlic and parsley), cuisses de grenouille à la poulette (egg and cream). Seven euros, or thereabouts, for a paper plateful, with fries. Nine with a beer or a glass of not-very-chilled riesling. The more daring are offering cuisses de grenouilles à la vosgienne, à l’andalouse, à l’ailloli. There’s pizza grenouille, quiche grenouille, tourte grenouille. Omelette de grenouilles aux fines herbes. Souffle, cassolette and gratin de grenouilles.

Everywhere you look, people are nibbling greasily on a grenouille, licking their fingers, spitting out little bones. “Isn’t it just great?” yells Jacky’s diminutive wife, Frederique. “Every year we do this. It’s our tradition. Our tribute to the noble frog.”

This is Vittel’s 37th annual Foire aux Grenouilles. According to Roland Boeuf, the 70-year-old president of the Confrererie de Taste-Cuisses de Grenouilles de Vittel, or (roughly) the Vittel Brotherhood of Frog Thigh Tasters, which has organised the event since its inception, the fair regularly draws upwards of 20,000 gourmet frog aficionados to the town for two days of amphibian-inspired jollities. Between them, they consume anything up to seven tonnes of frogs’ legs.

But there’s a problem. When the fair began, its founder René Clément, resistance hero, restaurateur and last of the great Lorraine frog ranchers, could supply all the necessary amphibians from his lakes 20 miles or so away. Nowadays, none of the frogs are even French.

According to Boeuf, Clément, whose real name was Hofstetter, moved to the area in the early 1950s looking to raise langoustines in the Saone river; the water proved too brackish and he turned to frogs instead. A true Frenchman, his catchphrase, oft-quoted around these parts, was that frogs “are like women. The legs are the best bits”.

Hofstetter/Clément would, says Gisèle Robinet, “provide 150 kg, 200 kg for every fair, all from his lakes and all caught by him”. With her husband Patrick, Robinet runs the Au Pêché Mignon patisserie (tourte aux grenouilles for six, €18; chocolate frogs €13 the dozen) on the Place de Gaulle, across the square from the restaurant Clément used to run, Le Grand Cerf. Now known as Le Galoubet, there’s a plaque commemorating the great frogman outside. “As a child I remember clearly him dismembering and preparing and cleaning his frogs in front of the restaurant,” says Robinet, who sells frog tartlets to gourmet Vitellois throughout the year, but makes a special effort with quiches and croustillants at fair-time. “It’s a big job, you know. Very fiddly. But we were all frog-catchers when I was a kid. Now, of course, that’s not possible any more.”

Boeuf recalls many a profitable frog-hunting expedition in the streams and ponds around Vittel. “One sort, la savatte, you could catch with your bare hands,” he says. “Best time was in spring, when they lay their eggs. They’d gather in their thousands, great wriggling green balls of them. I’ve seen whole streams completely blocked by a mountain of frogs.”

Others, rainettes, would be everywhere at harvest time. Or you could get a square of red fabric and lay it carefully on the water next to a lily pad that happened to have a frog on it, “and she’d just hop straight off and on to the cloth”, Boeuf says. “They love red.”

Pierette Gillet, the longest-standing member of the Brotherhood and, at 81, still a sprightly and committed frog-fancier, remembers heading out at night with a torch in search of so-called mute frogs, harder to catch because they have no larynx and hence emit no croak. “They’d be blinded by the light, and you could whack them over the head,” she says.

But those days are long gone. As elsewhere in the world, the amphibians’ habitat in France – where frogs’ legs have been a recognised and much remarked-upon part of the national diet for the best part of 1,000 years – is increasingly at risk, from pollution, pesticides and other man-made ills. Ponds have been drained and replaced with crops and cattle-troughs. Diseases have taken their toll, and the insects that frogs feed on are disappearing too. Alarmed by a rapid and dramatic fall in frog numbers, the French ministry of agriculture and fisheries began taking measures to protect the country’s species in 1976; by 1980, commercial frog harvesting was banned.

These days, a few regional authorities in France still allow the capture of limited numbers of frogs, strictly for personal consumption and provided they are broiled, fried or barbecued and consumed on the spot (a heresy not even Boeuf is prepared to contemplate). There are poachers who defy the ban; two years ago a court in Vesoul in the Haute-Saone convicted four men of harvesting vast numbers of frogs from the Mille-Etangs or Thousand Lakes area of the Vosges. The ringleader admitted to personally catching at least 10,000, which he sold to restaurants for 32 cents apiece.

By and large, though, France’s tough protection laws, enforceable by fines of up to €10,000 (£8,500) and instant confiscation of vehicles and equipment, seem to be working. As a result, all seven tonnes (officially, at least) of frogs’ legs consumed at this year’s Vittel fair have been imported, pre-prepared, deep-frozen and packed in cardboard boxes, from Indonesia.

Needless to say, this does not much please patriotic Gallic frog-fanciers. “We’d far prefer our frogs to be French, of course we would,” laments Gillet. “Especially here in the Vosges. This really is the heart of frog country.”

A Vittel restaurateur, who for obvious reasons demands anonymity, suggests there are still “ways and means” of securing at least a semi-reliable supply of French frogs for those who demand a true produit du terroir, “but it’s really not very easy, and no one here will tell you anything about it. We’d like to source locally, but the law is the law.”

But the fact that the Foire aux Grenouilles – not to mention the rest of France, and other big frog-consuming nations such as Belgium and the United States – now imports almost all its frogs’ legs has consequences that run deeper than a mere denting of national gastronomic pride. For scientists now believe that, just as with many fish species, we could be well on the way to eating the world’s frogs to extinction. Based on an analysis of UN trade data, researchers think we may now be consuming as many as 1bn wild frogs every year. For already weakened frog populations, that is very bad news indeed.

Scientists have long been aware that while human activity is causing a steady loss of the world’s biodiversity, amphibians seem to be suffering far more severely than any other animal group. It is thought their two-stage life cycle, aquatic and terrestrial, makes them twice as vulnerable to environmental and climate change, and their permeable skins may be more susceptible to toxins than other animals. In recent years, a devastating fungal condition, chytridiomycosis, has caused catastrophic population declines in Australia and the Americas.

“Amphibians are the most threatened animal group; about one third of all amphibian species are now listed as threatened, against 23% of mammals and 12% of birds,” says Corey Bradshaw, an associate professor at the Environment Institute of the University of Adelaide and a member of the team that carried out the research into human frog consumption that was published earlier this year in the journal Conservation Biology. “The principle drivers of extinction, we always assumed, were habitat loss and disease. Human harvesting, we thought, was minor. Then we started digging, and we realised there’s this massive global trade that no one really knows much about. It’s staggering. So as well as destroying where they live, we’re now eating them to death.”

France is the main culprit: according to government figures, while the French still consume 70 tonnes a year of domestically gathered legs each year, they have been shipping in as many as 4,000 tonnes annually since 1995. Besides popular, essentially local events such as the Foire aux Grenouilles, frogs’ legs are mostly a delicacy reserved for restaurants with gastronomic pretensions; one three-star chef, Georges Blanc, has at one time or another developed 19 different recipes for them at his celebrated restaurant in the Ain village of Vonnas, baking and skewering and skilleting them in everything from cream to apples.

Belgium and Luxembourg are also noted connoisseurs, but perhaps surprisingly, the country that runs France closest in the frog import stakes is the US. Frogs’ legs are particularly popular in the former French colony of Louisiana, where the city of Rayne likes to call itself Frog Capital of the World, but are also consumed with relish in Arkansas and Texas, where they are mostly served breaded and deep-fried. Bradshaw has a picture on his blog of President Barack Obama tucking with apparent gusto into a plate of frogs’ legs.

The world’s most avid frog eaters, though, are almost certainly in Asia, in countries such as Indonesia, China, Thailand and Vietnam. South America, too, is a big market. “People may think frogs’ legs are some kind of epicurean delicacy consumed by a handful of French gourmets, but in many developing countries they are a staple,” Bradshaw says.

Indonesia is today the world’s largest exporter of frogs by far, shipping more than 5,000 tonnes each year. Some of these may be farmed, but not many. Commercial frog-farming has been tried in both the US and Europe, but with little success: for a raft of reasons, including the ease with which frogs can fall prey to disease, feeding issues and basic frog biology, it is a notoriously risky and uneconomic business. Frogs are farmed in Asia, but rarely on an industrial scale; most are small, artisan affairs with which rural families try to supplement their income.

The vast majority of frogs that end up on a plate are harvested from the wild. Bradshaw and his colleagues estimate that Indonesia, to take just one exporting country, is probably consuming between two and seven times as many frogs as it sends abroad. “We have the legally recorded, international trade figures, but none of the local business is recorded,” Bradshaw says. “It’s back-of-an-envelope work. That’s what’s so alarming.”

The scientists’ biggest concern, he says, is that because of the almost complete lack of data, no one knows in what proportion different frog species are being taken. If, as they suspect, some 15 or 20 frog species are at any given moment supplying most of world demand, the consequences could be catastrophic. For while overharvesting for human consumption may not in itself be quite enough to drive a frog species to extinction, combined with all the other threats frogs face it certainly could be.

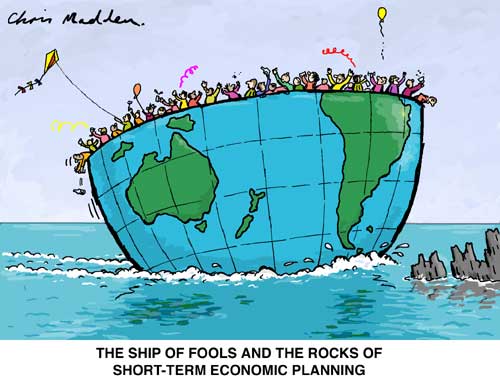

“The thing is, it isn’t a gradual process,” Bradshaw warns. “There’s a threshold, you cross it, and the whole thing crashes because you’ve just completely changed the composition of the whole community. There’s a tipping point. It’s exactly what happened with the overexploitation of cod in the North Atlantic. And with frogs, there’s no data, no tracking, no stock management. We really should have learned our lesson with fish, but it seems we haven’t. This is a wake-up call.”

Back in Vittel, Boeuf says he had no idea frogs were in such trouble. “They’re an endangered species here, I know,” he says. “That’s why we have to be careful, and we are. But if we can buy them in such quantities from Indonesia, surely it must be all right. They’re being careful there too, aren’t they?” Sadly, it would seem they are not. And all for a few greasy scraps of limp, bland flesh.

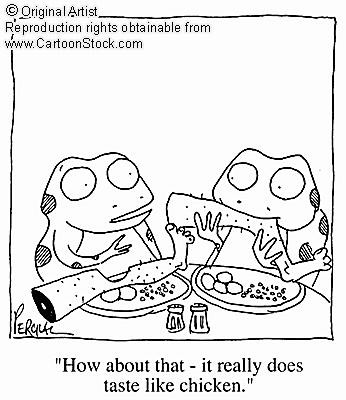

People say frogs taste like a cross between fish and chicken. In fact, they taste of frog: in other words, precious little bar the sauce they are served in.

“…nobody puts a value on pollination; national accounts do not reflect the value of ecosystem services that stop soil erosion or provide watershed protection.“

“…nobody puts a value on pollination; national accounts do not reflect the value of ecosystem services that stop soil erosion or provide watershed protection.“

Sharks worldwide are in trouble (well, so are many taxa, for that matter), with

Sharks worldwide are in trouble (well, so are many taxa, for that matter), with  Last month David Agnew and colleagues published a paper in

Last month David Agnew and colleagues published a paper in