Those of us living with cats share our homes with an ancestral predator, one adapted for hunting and the frequent, exclusive consumption of meat. These instincts become fully activated outside the domestic environment, where cats pose a global threat to wildlife.

Pets are family. We celebrate their arrival with the same joy as a grand homecoming, and their absence leaves a grief as deep as losing a loved one. In bonding with cats and dogs, we often attribute human abilities and emotions to them.

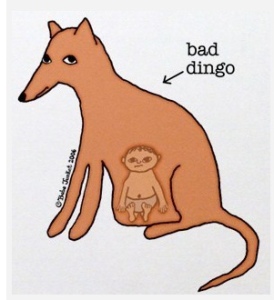

But beyond this affection, domestic animals still carry the instincts and genetic legacy of their wild ancestors(1, 2). My cats — Caruso, Muesli, and Plata — have been calm and loving, but they have always enjoyed a real hunt (3). When a moth comes in through a window, they seem possessed: their mouths chitter and make clicking sounds, they leap from one piece of furniture to another, and their heads snap sharply between the insect’s position and other points in the room, calculating the best spot from which to pounce on their prey. That is why when they become feral, cats and dogs integrate into food chains like any other species: they compete for ecosystem resources, hunt and are hunted, and hybridise and exchange diseases with other carnivores (4, 5).

Domestic cats are highly skilled hunters, and their predatory interactions with a wide range of prey are widely documented in social media and documentaries. Some examples include cats catching: bats and birds on the wing, butterflies, chipmunks, dragons, fishes, grasshoppers, frogs, lizards, mice, owls, rabbits, seagulls, snakes, squirrels, and wallabies. See an award-winning photo depicting wildlife with fatal injuries caused by cats recorded in 2019 at a single animal hospital in the USA, and a video showing domestic cats mimicking bird calls and some cat owners explaining that their pets reject commercial cat food after experiencing the thrill of hunting real prey. The documentary Secret Life of Cats contextualises the ecological challenges posed by free-roaming cats.

Read the rest of this entry »