It was a fun night at Parliament House in Canberra in front of a very prestigious crowd – most of the Vice Chancellors of Australian universities were present, along with many other distinguished guests. A little daunting, but the reception was very warm indeed.

After meeting the welcoming and congratulatory Elsevier/Scopus team during a pre-dinner reception, the other category winners (Ben Eggleton, Peter Love, Dan Li and Prash Sanders) and I were then escorted to the main event at Parliament House. Bernie Hobbs of ABC Science acted as master of ceremonies, and Senator Kim Carr presented the awards with Y. S. Chi of Elsevier. Prash and I were honoured to sit at the same table with the University of Adelaide’s Vice Chancellor, Professor James McWha.

The Higher Education supplement of the Australian published a few articles about the winners, and I reproduce the one describing my award and research below (article by C. Jones):

SHOOTERS in low-flying helicopters take out feral buffalo, horses and pigs that are wreaking havoc on Kakadu National Park.

There are no bullets and blood, however, as these are not real shooters and animals but silicon ones. They are cyber-entities, represented by numbers, generated in a computer model by mathematical ecologist Corey Bradshaw and his colleagues.

Land managers will be able to use the model to test scenarios in a virtual Kakadu National Park to work out the cheapest and best culling programs to limit the damage from the pests.

The mastery early in his career of mathematical modelling such as the Kakadu computer code has put Bradshaw at the forefront of conservation biology.

In naming him the Scopus young researcher of the year in the life sciences and biological sciences category, the judging panel says his modelling work has added “significant new perspectives and rigour” to his field.

Bradshaw grew up in western Canada. His interest in conservation was piqued when he ranged the Rocky Mountains of British Columbia with his father, who was a game trapper.

He later turned a knowledge of ecology that underpinned “killing things” to saving endangered species.

He obtained a bachelor of ecology from the University of Montreal in 1992. Research as part of a masters degree at the University of Alberta took him to northern Canada to study caribou. Later, he undertook a PhD in zoology at the University of Otago, Dunedin, with his research focusing on the population dynamics of fur seals.

The subjects of his fieldwork have ranged from the lowliest snails in Borneo, through penguins in Antarctica and frogs in Singapore, to Top End buffalo.

Some of his research is aimed at controlling pest species through an understanding of population dynamics. The goal of other work is to prevent extinctions of native species.

The research comes as the life sciences — once derided as the soft sciences — continue to harden up.

Like the so-called hard disciplines of physics and chemistry, biology is increasingly being structured by mathematics, and Bradshaw has been riding the wave.

The mathematics representing complex changes in populations as they boom, bust or stabilise in response to environmental factors is formidable. A paper on the Kakadu model, published recently in Methods in Ecology and Evolution, would not look out of place in a mathematics journal. It is full of equations, matrices and graphs.

“I realised the best thing I could do for my career was to get adept at mathematics,” he tells the HES. “You can’t do much of high value in conservation without it.

“The days of the natural historian walking around, casually drawing things and describing the reproductive structures of plants and animals are gone.

“We need to do the systematics as well, but the mathematics is a fundamental component of all biology now, especially ecology, because it’s such complex systems we’re dealing with.

“It’s chaos theory all the time.

“Trying to predict what an entire ecosystem is going to do gets very complicated very quickly, and mathematics is the only way to do it.”

Bradshaw’s Kakadu model divides the landscape into a grid. Equations in the model relate population size to demography for each element of the grid. Input demographic parameters include data obtained empirically through field studies: the age of individuals, the number of breeding females, and birth and mortality rates.

The program is run repeatedly, stepping forward in time, with the population size result of each run forming the initial condition of the next one.

“We can also do population viability analysis,” Bradshaw says. “We can make predictions on the probability that a population will go extinct within a certain period. It gives a window into the future.”

The work can deliver surprising results. Bradshaw’s team last year did an analysis for the federal government on the critically endangered grey nurse shark to find out the main factors in the species demise. The work showed that fishing was the biggest threat, not beach nets or a lack of protected areas, as previously suspected.

The results have influenced conservation policy, he says.

Other research suggests the Tasmanian devil, listed as endangered because of the devastating devil facial tumour disease that is ripping through populations, has recovered from big disease outbreaks before.

“We didn’t know that until we started looking at the demographic model,” Bradshaw says. “It is a scavenger, so it was probably exposed to a lot more diseases than your average animal.”

But he warns against complacency about the outbreak.

The modelling work has allowed him to make generalisations about the risk of extinction and that enables biodiversity managers to target their efforts.

“Five thousand is almost a magic number in conservation,” he says. “If you’re playing with less than that, you’re fighting a losing battle.”

The research also reveals which exotic species are likeliest to become invasive, knowledge valuable to biosecurity.

A consummate science communicator with a blog (ConservationBytes.com) and heavy community outreach schedule, Bradshaw is focusing on assessing the vulnerability of species to climate change.

And how do his models define Homo sapiens?

“They’re telling us that about 15 per cent of all the humans that ever lived are alive today,” he says. “That means that we are in the exponential phase of an invasion, much like rats on a new island or cockroaches in a new apartment.

“If we’re not careful, the very ecosystems that support our success will ensure our demise.”

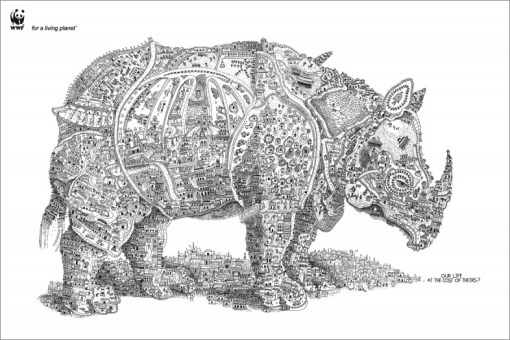

Given it’s only a little under 3 weeks away, I thought I’d advertise an upcoming free public lecture I’m giving for the University of Adelaide‘s highly popular Research Tuesdays programme.

Given it’s only a little under 3 weeks away, I thought I’d advertise an upcoming free public lecture I’m giving for the University of Adelaide‘s highly popular Research Tuesdays programme.