Conservation Letters has joined the Twitter-sphere.

Conservation Letters has joined the Twitter-sphere.

Click here to follow.

Click on the Journals page of ConservationBytes.com to access specific issues.

Conservation Letters has joined the Twitter-sphere.

Conservation Letters has joined the Twitter-sphere.

Click here to follow.

Click on the Journals page of ConservationBytes.com to access specific issues.

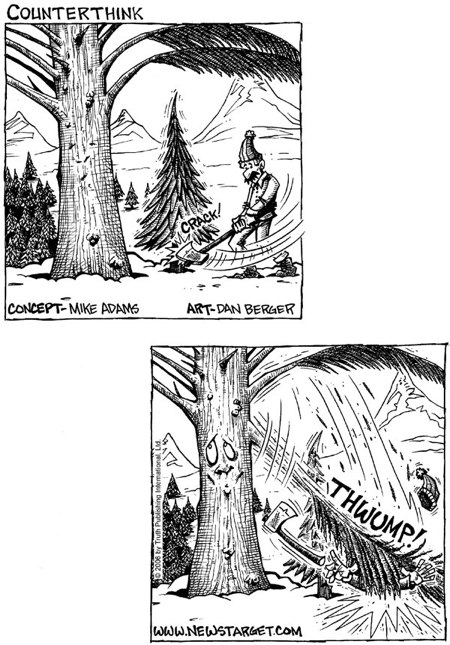

A recent report by Reuters highlighted in Mongabay.com about forest fires in Peninsular Malaysia and Sumatra reminded me of an important paper that appeared in Nature in 2007.

Lohman and colleagues’ paper entiled The burning issue gets my vote for a Potential spot at ConservationBytes.com.

Let’s face it, there is ample evidence now that countries in Southeast Asia can ill-afford any more deforestation, yet unregulated and illegal burning continues there despite international accords to reduce the intensity and frequency of fires. Lohman et al. highlighted how farmers throughout Indonesia and Malaysia in particular are ignoring fire bans and continuing to apply traditional techniques of burning off vegetation from plantations when new crops are to be seeded.

Common practice, been used for centuries – so what? Well the problem is that many of these fires burn out of control for weeks to months and continue into the remaining fragmented forests adjacent to agricultural land. With already altered moisture regimes from logging and agricultural clearing, drier forests are more susceptible, leading to broad scale fires that further threaten these important biodiversity hotspots.

If you are of the blinkered type that couldn’t give a rat’s bollocks about the loss of species (I hope not – otherwise you probably wouldn’t be reading this), then the human cost should convince you that something drastic needs to be done. These rampant and seemingly unending fire cycles cost billions to some of the world’s poorest nations in terms of material damage. Additionally, the haze associated with fires (remember the 1998 El Niñ0 event that saw 3 million km2 of Southeast Asia covered in haze affecting 70 million people?) is a major health hazard that cripples and kills hundreds of thousands of people.

For my Australian readers, don’t think this is restricted to Southeast Asia – burning is a major biodiversity and human health hazard here as well (see Johnston et al. 2002, 2007, Woinarksi 1999 and Pardon et al. 2003)

Clearly the burning has to stop.

I’ve written about The University of Adelaide‘s new Environment Institute not too long ago (see post here), and now we’ve had the official launch. The people behind scenes have put together a great introductory video that we all witnessed for the first time last week. Happy to share it with ConservationBytes.com readers here.

Vodpod videos no longer available.

A couple of other excellent parts of this evening include the venerable Robyn Williams‘ speech (listen here), and our Director’s, Professor Mike Young, encouraging kick off (listen here).

I’ve very proud to be a part of this exciting initiative.

Quick off the mark this month is the new issue of Conservation Letters. There are some exciting new papers (listed below). I encourage readers to have a look:

Policy Perspectives

Letters

Keeping with the oil palm theme…

A paper just published online in Conservation Letters by Venter and colleagues entitled Carbon payments as a safeguard for threatened tropical mammals gets my vote for the Potential list.

We’ve been saying it again and again and again… tropical forests, the biodiversity they harbour and the ecosystem services they provide are worth more to humanity than the potential timber they represent. Now we find they’re even worth more than cash crops (e.g., oil palm) planned to replace them.

A few years ago some very clever economists and environmental policy makers came up with the concept of ‘REDD’ (reducing carbon emissions from deforestation and forest degradation), which is basically as system “… to provide financial incentives for developing countries that voluntarily reduce national deforestation rates and associated carbon emissions below a reference level”. Compensation can occur either via grant funding or through a carbon-trading scheme in international markets.

Now, many cash-greedy corporations argue that REDD could in no way compete with the classic rip-it-down-and-plant-the-shit-out-of-it-with-a-cash-crop approach, but Venter and colleagues now show this argument to be a bit of a furphy.

The authors asses the financial feasibility of REDD in all planned oil palm plantations in Kalimantan – Indonesia’s part of the island of Borneo in South East Asia. Borneo is also the heart of the environmental devastation typical of the tropics. They conclude that REDD is in fact a rather financially competitive scheme if we can manage to obtain carbon prices of around US$10-33/tonne. In fact, even when carbon prices are as low as US$2/tonne (as they are roughly now on the voluntary market), REDD is still competitive for areas of high forest carbon content and lower agricultural potential.

But the main advantage isn’t just the positive cash argument – many endangered mammals (and there are 46 of them in Kalimantan) such as the South East Asian equivalent of the panda (the orang-utan – ‘equivalent’ in the media-hype and political sensitivity sense, not taxonomic, of course) and the Bornean elephant (yes, they have them) are currently found in areas planned for plantation. So saving the forest obviously saves these and countless other taxa that only exist on this highly endemic island. Finally, Venter and colleagues found that where emission reductions were cheapest, these are also areas with higher-than-average densities of endangered mammals, suggesting that REDD is a fantastic option to keep developing countries in the black without compromising their extensive species richness and endemism.

Brilliant. Now if we can just get the economists and pollies to agree on a REDD model that actually works.

A small opinion piece about to be published in Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment (June 2009 issue) discusses a major concern we (Lian Pin Koh, Rhett Butler and I) have with Indonesia’s decision to allow peatlands less than 3 m deep to be converted to oil palm. Is nothing immune to the spread of this crop (see previous posts here and here on oil palm plantations)?

Why is this such a big deal? Well, we list five main reasons why it’s a bad idea for Indonesia, the world in general and biodiversity:

More detail can be found in the Write Back piece that will be published shortly in Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment. For more information on oil palm and its conservation implications, see the following:

I’ve been meaning to blog on this for a while, but am only now getting around to it.

Now, it’s not bulldozers razing our underwater forests – it’s our own filth. Yes, we do indeed have underwater forests, and they are possibly the most important set of species from a biodiversity perspective in temperate coastal waters around the world. I’m talking about kelp. I’ve posted previously about the importance of kelp and how climate change poses a threat to these habitat-forming species that support a wealth of invertebrates and fish. In fact, kelp forests are analogous to coral reefs in the tropics for their role in supporting other biodiversity.

The paper I’m highlighting for the ConservationBytes.com Potential list is by a colleague of mine at the University of Adelaide, Associate Professor Sean Connell, and his collaborators entitled “Recovering a lost baseline: missing kelp forests from a metropolitan coast“. This paper is interesting, novel and applied for several reasons.

First, it sets out some convincing evidence that the Adelaide coastline has experienced a fairly hefty loss of canopy-forming kelp (mainly species like Ecklonia radiata and Cystophora spp.) since urbanisation (up to 70 % !). Now, this might not seem too surprising – we humans have a horrible track record for damaging, exploiting or maltreating biodiversity – but it’s actually a little unexpected given that Adelaide is one of Australia’s smaller major cities, and certainly a tiny city from a global perspective. There hasn’t been any real kelp harvesting around Adelaide, or coastal overfishing that could lead to trophic cascades causing loss through herbivory. Connell and colleagues pretty much are able to isolate the main culprits: sedimentation and nutrient loading (eutrophication) from urban run-off.

Second, one might expect this to be strange because other places around the world don’t have the same kind of response. The paper points out that in the coastal waters of South Australia, the normal situation is characterised by low nutrient concentrations in the water (what we term ‘oligotrophic’) compared to other places like New South Wales. Thus, when you add even a little bit extra to a system not used to it, these losses of canopy-forming kelp ensue. So understanding the underlying context of an ecosystem will tell you how much it can be stressed before all hell breaks loose.

Finally, the paper makes some very strong arguments for why good marine data are required to make long-term plans for conservation – there simply isn’t enough investment in basic marine research to ensure that we can plan responsibly for the future (see also previous post on this topic).

A great paper that uses a combination of biogeography, time series and chemistry to inform about a major marine conservation problem.

We all have a distorted view of the planet. Our particular experiences, drives, beliefs and predilections all taint our ability to perceive and interpret our world objectively and rationally.

We all have a distorted view of the planet. Our particular experiences, drives, beliefs and predilections all taint our ability to perceive and interpret our world objectively and rationally.

Enter science.

Science, in all its manifestations, aims, outcomes and applications, is united by one basic principle: to reduce human subjectivity. Contrary to popular belief, science isn’t a ‘thing’; and it’s certainly not a belief system. It isn’t even a philosophy (although there are several different major branches of the philosophy of science). It is, put way too simplistically, a method that attempts to isolate pattern from noise and objectivity from desire. It’s by no means a perfect system because human subjectivity can still creep in even when we make our best attempts to avoid it, but it’s the best system we have. Chances are too that if you’ve made a mistake and haven’t been as objective as you could have been, some other scientist will come along and rip down your house of cards. Two steps forward and one step back. That’s science.

So, where am I going? You might have seen this before, but I thought it worthwhile reproducing some of the images from Daniel Dorling, Mark Newman and Anna Barford’s The Atlas of the Real World: Mapping the Way We Live (Thames & Hudson 2008). There are some fascinating images of the world map that alter the ‘volume’ of a country relative to a particular resource use or conservation measure. The example shows the use of coal power, ecological footprint, forest depletion, water depletion, waste recycled, extinct species, species at risk, plants at risk, mammals at risk (check out the IUCN Red List for the last 4 categories), greenhouse gas emissions, energy depletion, and biocapacity. Check out your country and see how well or poorly you’re doing relative to the rest of the world.

“…nobody puts a value on pollination; national accounts do not reflect the value of ecosystem services that stop soil erosion or provide watershed protection.“

Barry Gardiner, Labour MP for Brent North (UK), Co-chairman, Global Legislators Organisation‘s International Commission on Land Use Change and Ecosystems

Last week I read with great interest the BBC’s Green Room opinion article by Barry Gardiner, Labour MP in the UK, about how the biodiversity crisis takes very much the back seat to climate change in world media, politics and international agreements.

He couldn’t be more spot-on.

I must stipulate right up front that this post is neither a whinge, rant nor lament; my goal is to highlight what I’ve noticed about the world’s general perception of climate change and biodiversity crisis issues over the last few years, and over the last year in particular since ConservationBytes.com was born.

Case in point: my good friend and colleague, Professor Barry Brook, started his blog BraveNewClimate.com a little over a month (August 2008) after I managed to get ConservationBytes.com up and running (July 2008). His blog tackles issues regarding the science of climate change, and Barry has been very successful at empirically, methodically and patiently tearing down the paper walls of the climate change denialists. A quick glance at the number views of BraveNewClimate.com since inception reveals about an order of magnitude more than for ConservationBytes.com (i.e., ~195000 versus 20000, respectively), and Barry has accumulated a total of around 4500 comments compared to just 231 for ConservationBytes.com. The difference is striking.

Now, I don’t begrudge for one moment this disparity – quite the contrary – I am thrilled that Barry has managed to influence so many people and topple so effectively the faecal spires erected by the myriad self-proclaimed ‘experts’ on climate change (an infamous line to whom I have no idea to attribute states that “opinions are like arseholes – everyone’s got one”). Barry is, via BraveNewClimate.com, doing the world an immense service. What I do find intriguing is that in many ways, the biodiversity crisis is a much, much worse problem that is and will continue to degrade human life for millennia to come. Yet as Barry Gardiner observed, the UK papers mentioned biodiversity only 115 times over the last 3 months compared to 1382 times for climate change – again, that order-of-magnitude disparity.

There is no biodiversity equivalent of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (although there are a few international organisations tackling the extinction crisis such as the United Nation’s Environment Program, the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment and the International Union for Conservation of Nature), we still have little capacity or idea how to incorporate the trillions of dollars worth of ecosystem services supplied every year to us free of charge, and we have nothing at all equivalent to the Kyoto Protocol for biodiversity preservation. Yet, conservation biologists have for decades demonstrated how human disease prevalence, reduction in pollination, increasing floods, reduced freshwater availability, carbon emissions, loss of fish supplies, weed establishment and spread, etc. are all exacerbated by biodiversity loss. Climate change, as serious and potentially apocalyptic as it is, can be viewed as just another stressor in a system stressed to its limits.

Of course, the lack of ‘interest’ may not be as bleak as indicated by web traffic; I believe the science underpinning our assessment of biodiversity loss is fairly well-accepted by people who care to look into these things, and the evidence spans the gambit of biological diversity and ecosystems. In short, it’s much less controversial a topic than climate change, so it attracts a lot less vitriol and spawns fewer polemics. That said, it is a self-destructive ambivalence that will eventually come to bite humanity on the bum in the most serious of ways, and I truly believe that we’re not far off from major world conflicts over the dwindling pool of resources (food, water, raw materials) we are so effectively destroying. We would be wise to take heed of the warnings.

![]()

The April issue of Conservation Letters is now out (a little late, but worth the wait). There are some good titles in this one, and I’ve blogged about a few of them already:

Happy reading!

I recently did an interview for the Reef Tank blog about my research, ConservationBytes.com and various opinions about marine conservation in general. I’ve been on about ‘awareness’ raising in biodiversity conservation over the last few weeks (e.g., see last post), saying that it’s really only the first step. To use an analogy, alcoholics must first recognise and accept that they are indeed drunks with a problem before than can take the (infamous AA) steps to resolve it. It’s not unlike biodiversity conservation – I think much of the world is aware that our forests are disappearing, species are going extinct, our oceans are becoming polluted and devoid of fish, our air and soils are degraded to the point where they threaten our very lives, and climate change has and will continue to exacerbate all of these problems for the next few centuries at least (and probably for much longer).

We’ve admitted we have a disease, now let’s do something about it.

Read the full interview here.

When I first saw this on the BBC I thought to myself, “Well, just another toothless celebrity ego-stroke to make rich people feel better about the environmental mess we’re in” (well, I am a cynic by nature). I have blogged before on the general irrelevancy of celebrity conservation. But then I looked closer and saw that this was more than just an ‘awareness’ campaign (which alone is unlikely to change anything of substance). The good Prince of Wales and his mates/offspring have put forward The Prince’s Rainforest Project, which (thankfully) not only endeavours to raise awareness about the true value of rain forests, it actually proposes a mechanism to do so. It took a bit to find, but the 52-page report on the PRP website outlines from very sensible approaches. In essence, it all comes down to money (doesn’t everything?).

Their proposed plan to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) details some of the following required changes:

Payments to rain forest nations for not deforesting (establish transaction costs and setting short-term ‘conservation aid’ programmes)

Multi-year service agreements (countries sign up for multi-year targets based on easily monitored performance indicators)

Fund alternative, low-carbon economic development plans (fundamental shifts in development targets that explicitly avoid deforestation)

Multi-stakeholder disbursement mechanisms (using funds equitably and minimising corruption)

Tropical Forests Facility (a World Bank equivalent with the express purpose of organising, disbursing and monitoring anti-deforestation money flow)

Country financing from public and private sources (funding initially derived from developed nations in form of ‘aid’)

Rain forest bonds in private capital markets (value country-level ‘income’ as interest payments and incentives within a trade framework)

Nations participate when ready (giving countries the option to advance at the pace dictated by internal politics and existing development rates)

Accelerating long-term UNFCCC agreement on forests (transition to independence post-package)

Global action to address drivers of deforestation (e.g., taxing/banning products grown on deforested land; ‘sustainability’ certification; consumer pressure; national procurement policies)

Now, I’m no economist, nor do I understand all the market nuances of the proposal, but it seems they are certainly on the right track. The value of tropical (well, ALL) forests to humanity are undeniable, and we’re currently in a state of crisis. Let’s hope the Prince and his mob can get the ball rolling.

For what it’s worth, here’s the video promoting the PRP. I could really care less what Harrison Ford and Pele have to say about this issue because I just don’t believe celebrities have any net effect on public behaviour (perceptions, yes, but not behaviour). But look beyond the superficiality and the cute computer-generated frog to the seriousness underneath. Despite my characteristically cynical tone, I give the PRP full support.

Vodpod videos no longer available.

An interesting new paper just appeared online (uncorrected proof stage) in Biological Conservation. Brewer and colleagues’ paper entitled Thresholds and multiple scale interaction of environment, resource use, and market proximity on reef fishery resources in the Solomon Islands describes how the proximity of fish markets explains some of the variation in fisheries takes on South Pacific coral reefs. Well, that may seem intuitive, you say – if you can’t access even a local market, chances are your fish will only feed you and your immediate family. Make an economic link to a larger pool of demanding consumers, and you have all the incentive you need to over-exploit your little patch of finned money.

An interesting new paper just appeared online (uncorrected proof stage) in Biological Conservation. Brewer and colleagues’ paper entitled Thresholds and multiple scale interaction of environment, resource use, and market proximity on reef fishery resources in the Solomon Islands describes how the proximity of fish markets explains some of the variation in fisheries takes on South Pacific coral reefs. Well, that may seem intuitive, you say – if you can’t access even a local market, chances are your fish will only feed you and your immediate family. Make an economic link to a larger pool of demanding consumers, and you have all the incentive you need to over-exploit your little patch of finned money.

Of course, the advent of better, more efficient transport (including refrigerated transport) and the development of local markets (i.e., tapping into larger ones in more populated areas) has inevitably caused fish depletions across the globe. Brewer and colleagues’ work provides a quantitative link between human demand and biodiversity decline (including ‘fishing down the web‘), and suggests that our best way to manage fisheries is to target the source of this demand – the markets and patterns of consumption. Ultimately, it’s the consumer that will dictate what does and what does not go extinct (see also previous post on consumer preferences for rare species). After all, if there’s a demand, someone will step in to provide the resource (provided it’s still there). Better education, smarter consumption and regulation along the entire chain will be far more effective in the long run than just attempting to control the fishers’ behaviour.

I’ve just spent the last few days in Sydney attending a workshop on the Eastern Seaboard Climate Change Initiative which is trying to come to grips with assessing the rising impact of climate change in the marine environment (both from biodiversity and coastal geomorphology perspectives).

Often these sorts of get-togethers end up doing little more than identifying what we don’t know, but in this case, the ESCCI (love that acronym) participants identified some very good and necessary ways forward in terms of marine research. Being a biologist, and given this is a conservation blog, I’ll focus here on the biological aspects I found interesting.

The first part of the workshop was devoted to kelp. Kelp? Why is this important?

As it turns out, kelp forests (e.g., species such as Ecklonia, Macrocystis, Durvillaea and Phyllospora) are possibly THE most important habitat-forming group of species in temperate Australia (corals and calcareous macroalgae being more important in the tropics). Without kelp, there are a whole host of species (invertebrates and fish) that cannot persist. The Australian marine environment is worth something in the vicinity of $26.8 billion to our economy each year, so it’s pretty important we maintain our major habitats. Unfortunately, kelp is starting to disappear around the country, with southern contractions of Durvillaea, Ecklonia and Hormosira on the east coast linked to the increasing southward penetration of the East Australia Current (i.e., the big current that brings warm tropical water south from Queensland to NSW, Victoria and now, Tasmania). Pollution around the country at major urban centres is also causing the loss or degradation of Phyllospora and Ecklonia (e.g., see recent paper by Connell et al. in Marine Ecology Progress Series). There is even some evidence that disease causing bleaching in some species is exacerbated by rising temperatures.

Some of the key kelp research recommendations coming out of the workshop were:

The second part of the discussion centred on ocean acidification and increasing CO2 content in the marine environment. As you might know, increasing atmospheric CO2 is taken up partially by ocean water, which lowers the availability of carbonate and increases the concentration of hydrogen ions (thus lowering pH or ‘acidifying’). It’s a pretty worrying trend – we’ve seen a drop in pH already, with conservative predictions of another 0.3 pH drop by the end of this century (equating to a doubling of hydrogen ions in the water). What does all this mean for marine biodiversity? Well, many species will simply not be able to maintain carbonate shells (e.g., coccolithophore phytoplankton, corals, echinoderms, etc.), many will suffer reproductive failure through physiological stress and embryological malfunction, and still many more will be physiologically stressed via hypercapnia (overdose of CO2, the waste product of animal respiration).

Many good studies have come out in the last few years demonstrating the sensitivity of certain species to reductions in pH (some simultaneous with increases in temperature), but some big gaps remain in our understanding of what higher CO2 content in the marine environment will mean for biota. Some of the key research questions in this area identified were therefore:

As you can imagine, the conversation was complex, varied and stimulating. I thank the people at the Sydney Institute of Marine Science for hosting the fascinating discussion and I sincerely hope that even a fraction of the research identified gets realised. We need to know how our marine systems will respond – the possibilities are indeed frightening. Ignorance will leave us ill-prepared.

I’m off to a conference shortly, so this will be brief.

In an effort to raise awareness about the plight of amphibians (see previous posts on ConservationBytes.com regarding drivers of amphibian extinction risk and over-harvesting frogs for human consumption), the mob at SaveTheFrogs.com have initiated ‘Save The Frogs Day’ for tomorrow (28 April 2009).

I encourage people to get involved – there are some particularly good ideas for teachers and students found at the dedicated ‘Save The Frogs Day’ website.

Sharks worldwide are in trouble (well, so are many taxa, for that matter), with ignorance, fear, and direct and indirect exploitation (both legal and illegal) accounting for most of the observed population declines.

Sharks worldwide are in trouble (well, so are many taxa, for that matter), with ignorance, fear, and direct and indirect exploitation (both legal and illegal) accounting for most of the observed population declines.

Despite this worrisome state (sharks have extremely important ‘regulatory’ roles in marine ecosystems), many people have been slowly taking notice of the problem, largely due to the efforts of shark biologists. An almost religious-like pillar of shark conservation that has emerged in the last decade or so is that if we save nursery habitats, all shark conservation concerns will be addressed.

Why? Many shark species appear to have fairly discrete coastal areas where they either give birth or lay eggs, and in which the young sharks develop presumably in relative safety from predators (including their parents). Meanwhile, breeding parents will often skip off as soon as possible and spend a good proportion of their non-breeding lives well away from coasts. Sexual segregation appears to be another common feature of many sharks species (the boys and girls don’t really play together that well).

The upshot is that if you conserve these more vulnerable ‘nursery’ areas in coastal regions, then you’ve protected the next generation of sharks and all will be fine. The underlying reason for this assumption is that it’s next-to-impossible to conserve entire ocean basins where the larger adults may be frolicking, but you can focus your efforts on restricted coastal zones that may be undergoing a lot of human-generated modification (e.g., pollutant run-off, development, etc.).

However, a new paper published recently in Conservation Letters entitled Reassessing the value of nursery areas to shark conservation and management disputes this assumption. Michael Kinney and Colin Simpfendorfer explain that even if coastal nurseries can be properly identified and adequately conserved, there is mounting evidence that failing to safeguard the adult stages could ultimately sustain declines or arrest recovery efforts. The authors support continuing efforts to identify and conserve nurseries, but they say this isn’t enough by itself to solve any real problems. If we want sharks around (and believe me, even though the odd swimmer may get a nip or two, it’s better than the alternative of no sharks), then we’re going to have to restrict fishing effort on the high seas as well.

I think this one qualifies for the ‘Potential‘ list.

Just a quick one while I wade through the swamp of overdue deadlines.

Just a quick one while I wade through the swamp of overdue deadlines.

Despite years of conservation biologists telling the world about the woeful state of the world’s forests, the loss of essential ecosystem services and the biodiversity extinction crisis, it seems the message doesn’t really get out. I’m in a state of semi-shock about the following Reuters release on the potential deal to deforest 10 million hectares for agricultural expansion in the Republic of Congo. There isn’t a single mention of the deforestation aspects or what it will mean for the Congolese. Sure, turn your country (the last remaining large tracts of rainforest in Africa) into a paddock, and see how long your ‘food security’ lasts under climate change. From poor to destitute in a matter of decades.

South African farmers have been offered 10 million hectares of farm land to grow maize, soya beans as well as poultry and dairy farming in the Republic of Congo, South Africa’s main farmers union said on Wednesday.

The deal, which covers an area more than twice the size of Switzerland, could be one of the biggest such land agreements on the continent agreed by Congo’s government in an effort to improve food security, Theo de Jager, deputy president of Agriculture South Africa (AgriSA), told Reuters.

South Africa has one of the most developed agriculture sectors on the continent, and is Africa’s top maize producer and No.3 wheat grower.

“They’ve given us 10 million hectares, and that’s quite big when you consider that in South Africa we have about 6 million hectares of land that is arable,” De Jager told Reuters on the sidelines of an agriculture conference in Durban.

De Jager said the agreement — to be finalised in South Africa next month — would operate as a 99-year lease at no cost, with additional tax benefits.

“The offer which we got and we’ve agreed on paper, is a 99-year lease, of which the value would be zero and it’s not allowed to escalate over the 99 years. So it is free use for 99 years,” he said.

The Republic of the Congo’s population of around 4 million people is concentrated in the southwest, leaving the vast areas of tropical jungle in the north virtually uninhabited.

De Jager said some 1,300 South African farmers were keen to farm in the Congo Republic.

“We have two groups of farmers who are interested, one of farmers who want to leave South Africa and relocate entirely to farm over there and another of farmers who want to diversify their farming operations to the Congo,” he said.

“We’ve got guys wanting to get into poultry and dairy farming, as well as maize and soya bean production.”

TAX HOLIDAYS

“It is a tax holiday for the first five years and you’re also exempted from import tax on all your agricultural inputs and equipment,” he said.

“So you can import directly from the source and take all your profits out for the duration of this lease,” he said.

He said there was a government-to-government bilateral agreement on the promotion and protection of investments.

“There are also rules for disengagement, for example if they find oil or minerals on your farm they can move you off, but compensate you for the loss of income and they must give you land to the same value or more in a different area,” he said.

De Jager said food in Congo was expensive because the country lacks an established agriculture sector and most of its foodstuff is imported.

“On their side, (the Congo government) is promising the Congolese that they will be self-sufficient in food production in five years, and the way they want to do it is by importing, according to them, high technology farmers,” De Jager said.

South African farmers had also been invited to farm in Mozambique, Angola, Nigeria, Libya, Kenya, Democratic Republic of Congo, Malawi and Zambia, he said.

And the most degraded and self-flagellating humour on Earth continues (see also previous instalments here, here and here) …

An excellent article by Andrew Simms (policy director of the New Economics Foundation) posted by the BBC:

An excellent article by Andrew Simms (policy director of the New Economics Foundation) posted by the BBC:

“It is like having a Commission on Household Renovation agonise over which expensive designer wallpaper to use for papering over plaster cracks whilst ignoring the fact that the walls themselves are collapsing on subsiding foundations.“

While most governments’ eyes are on the banking crisis, a much bigger issue – the environmental crisis – is passing them by, says Andrew Simms. In the Green Room this week, he argues that failure to organise a bailout for ecological debt will have dire consequences for humanity.

“Nature Doesn’t Do Bailouts!” said the banner strung across Bishopsgate in the City of London.

Civilisation’s biggest problem was outlined in five words over the entrance to the small, parallel reality of the peaceful climate camp. Their tents bloomed on the morning of 1 April faster than daisies in spring, and faster than the police could stop them.

Across the city, where the world’s most powerful people met simultaneously at the G20 summit, the same problem was almost completely ignored, meriting only a single, afterthought mention in a long communiqué.

World leaders dropped everything to tackle the financial debt crisis that spilled from collapsing banks.

Gripped by a panic so complete, there was no policy dogma too deeply engrained to be dug out and instantly discarded. We went from triumphant, finance-driven free market capitalism, to bank nationalisation and moving the decimal point on industry bailouts quicker than you can say sub-prime mortgage.

But the ecological debt crisis, which threatens much more than pension funds and car manufacturers, is left to languish.

It is like having a Commission on Household Renovation agonise over which expensive designer wallpaper to use for papering over plaster cracks whilst ignoring the fact that the walls themselves are collapsing on subsiding foundations.

Here’s a guest post from one of my newest PhD students, Jarod Lyon of the Arthur Rylah Institute in Victoria. He’s introducing some of his ongoing work and how he incorporates anglers into conservation research.

As most conservationists know, snags (fallen trees and branches in rivers) are the riverine equivalent of marine reefs, providing critical habitat for many plants and animals, from microscopic bacteria, fungi and algae through to large native fish. They are the places where the greatest numbers and diversity of organisms occur in lowland sections of rivers. Their presence has an important influence on the overall health of these rivers.

Ins southern Australia, Murray cod, trout cod and golden perch are three iconic fish species that occur in the Murray River (Figure 1). Recent investigations into the ecology of these species have demonstrated a strong dependence on the presence of snags – a relationship well-known to recreational anglers who target both Murray cod and golden perch. Unfortunately, the abundance of these species has declined over the past 100 years and they are now considered threatened. Excessive removal of snags has been identified as a primary cause for this decline. For example, in the Lake Hume to Lake Mulwala reach of the Murray River, over 25000 snags were removed in the 1970s and 1980s to improve the passage of water between Lake Hume and the large irrigation channels at Yarrawonga.

The largest resnagging project ever undertaken in Australia is now in full swing. It aims to reverse the legacy of clearing snags that has occurred along the Murray reaches since European settlement. The resnagging is occurring in the Hume-Mulwala reach of the Murray using trees that were cleared for the Hume Highway extension between Albury and Tarcutta, and will create substantially more physical habitat for native fish in this reach of the river. By creating this habitat, the size of the native fish population in this reach is expected to increase thereby improving the conservation status of the native species present, and improving the quality of the recreational fishery for native species (particularly Murray cod and golden perch). It is the largest project of its kind ever undertaken in Australia, and is a great step towards recovering fish populations. The project is funded under the Murray Darling Basin Commission‘s Living Murray Program, and is being undertaken by a variety of state and national organisations, in particular NSW Department of Primary Industries and Victorian Department of Sustainability and Environment (DSE).

To ensure that the resnagging is having a beneficial effect on the numbers of native fish in the reach, a comprehensive monitoring and evaluation program is being implemented by scientists from the DSE’s Arthur Rylah Institute. This program is determining whether an increase in the size of the native fish populations is the result of:

To measure these changes, the fish populations between Hume Dam and Lake Mulwala are being surveyed once a year to determine the population size and level of recruitment. For the purpose of comparison, surveying between Yarrawonga and Tocumwal, in the lower Ovens River, and in Lake Mulwala, is also being undertaken.

Some of the fish caught (Figure 2) will be tagged with an external tag, internal tag or radio transmitter (Figures 3 & 4). All tags have a unique number that identifies the individual. The recapture of these individuals, both by researchers and by anglers, allows survival and movement patterns to be measured.

The external tags are plastic polymer tags and are easily visible, protruding from the dorsal fin area. These tags are used to allow information from anglers to be directly used in the monitoring. A phone number is printed on each tag and when anglers call this number to report that they have caught a tagged fish, this provides valuable information on the not only fish survival and growth, but also the performance of the recreational fishery. These tags have a lifespan of 2-5 years. Anglers who call in tag information are also eligible for a reward (usually a stubby holder or lure) and get sent a certificate which gives details of the history of the fish which they have captured and reported.

The internal tags are implanted into the area to the front of the pectoral fin, are not visible, and unlike the external tags, are permanent. The tags are passive integrated transponder (PIT) tags (Figure 4), similar to those used in the pet and livestock industry. The tags are important as they allow a long-term record of fish survival, growth and movement to be measured. Fishways across the Murray Darling Basin are increasingly being installed with readers that can detect these tags. This can give researchers valuable information on long-range movements. For example, one fish (a 20-kg Murray cod) that was tagged in the Murray river near Corowa, was picked up on a PIT tag reader at the bottom of the Torrumbarry Weir fishway – a fair feat when you consider that this fish has had to get through both Mulwala and Torrumbarry Weirs, as well as travel a distance of over 200 river km downstream!

Radio transmitters are surgically inserted into the body cavity of the fish (Figure 3). These tags emit a radio signal that can be tracked continuously (Figure 5), and allow a rapid assessment of the movements (i.e., emigration and immigration rates) of a population to be determined. The tags are also detected by an array of 18 logging stations located along the river between Lake Hume and Barmah (Figure 1). Approximately 1000 radio tags will be implanted over the life of the project – making it possibly the largest radio-tagging program in the country.

If you catch a tagged fish, please record the type of fish, its number, its length (and its weight if possible) and the location of its capture and report this information on the phone number printed on the tag. These angler records improve the quality of the data collected and reporting of angler captures is encouraged through the rewards program.

As well as the general tag return program, a more targeted “Research Angler Program” is being undertaken. The angler program commenced operations in July 2007. The project was developed to assist with the scientific monitoring and communication requirements of the native fish habitat restoration project.

This section of the monitoring recognises that local anglers can contribute information about the state of native fish in the River Murray by recording their fishing effort and the amount of fish captured. Such information, in addition to greatly increasing the community awareness of the monitoring program, also adds another ‘string to the monitoring bow’ in that it will form a long-term dataset of fish captures, which can eventually be linked to the resnagging effort. The information gathered will be entered into a database and analysed to help assess changes in fish population size in relation to the habitat rehabilitation project.

Figure 5

Instream woody habitat is a vital component to the lifecycle of Murray Cod and the endangered trout cod. The resnagging of the River Murray – Hume Dam to Yarrawonga, will conserve and enhance native fish communities. Continual monitoring and interactions with the local angling fraternity is a crucial part of the success of this project.

The anglers have logbooks and have been trained in removing the otoliths, which are the earbones, from fish that they are taking for the table. We can then use the otoliths to determine the age and growth of the fish in response to the resnagging work.

Since December 2007 the fishers with the resnagging Angler Monitoring Program have captured over 65 Murray Cod, with over 95% of these fish released. Anglers have caught and released other native species such as golden perch and the endangered trout cod.