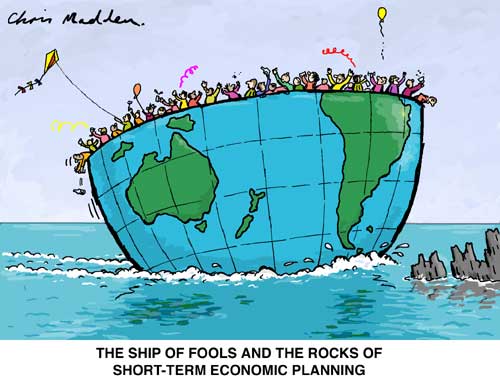

When I first saw this on the BBC I thought to myself, “Well, just another toothless celebrity ego-stroke to make rich people feel better about the environmental mess we’re in” (well, I am a cynic by nature). I have blogged before on the general irrelevancy of celebrity conservation. But then I looked closer and saw that this was more than just an ‘awareness’ campaign (which alone is unlikely to change anything of substance). The good Prince of Wales and his mates/offspring have put forward The Prince’s Rainforest Project, which (thankfully) not only endeavours to raise awareness about the true value of rain forests, it actually proposes a mechanism to do so. It took a bit to find, but the 52-page report on the PRP website outlines from very sensible approaches. In essence, it all comes down to money (doesn’t everything?).

Their proposed plan to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) details some of the following required changes:

-

Payments to rain forest nations for not deforesting (establish transaction costs and setting short-term ‘conservation aid’ programmes)

-

Multi-year service agreements (countries sign up for multi-year targets based on easily monitored performance indicators)

-

Fund alternative, low-carbon economic development plans (fundamental shifts in development targets that explicitly avoid deforestation)

-

Multi-stakeholder disbursement mechanisms (using funds equitably and minimising corruption)

-

Tropical Forests Facility (a World Bank equivalent with the express purpose of organising, disbursing and monitoring anti-deforestation money flow)

-

Country financing from public and private sources (funding initially derived from developed nations in form of ‘aid’)

-

Rain forest bonds in private capital markets (value country-level ‘income’ as interest payments and incentives within a trade framework)

-

Nations participate when ready (giving countries the option to advance at the pace dictated by internal politics and existing development rates)

-

Accelerating long-term UNFCCC agreement on forests (transition to independence post-package)

-

Global action to address drivers of deforestation (e.g., taxing/banning products grown on deforested land; ‘sustainability’ certification; consumer pressure; national procurement policies)

Now, I’m no economist, nor do I understand all the market nuances of the proposal, but it seems they are certainly on the right track. The value of tropical (well, ALL) forests to humanity are undeniable, and we’re currently in a state of crisis. Let’s hope the Prince and his mob can get the ball rolling.

For what it’s worth, here’s the video promoting the PRP. I could really care less what Harrison Ford and Pele have to say about this issue because I just don’t believe celebrities have any net effect on public behaviour (perceptions, yes, but not behaviour). But look beyond the superficiality and the cute computer-generated frog to the seriousness underneath. Despite my characteristically cynical tone, I give the PRP full support.

Vodpod videos no longer available.

I’m recommending you view a video presentation (can be accessed by clicking the link below) by A/Prof. David Paton which demonstrates the urgency of reforesting the region around Adelaide. Glenthorne is a 208-ha property 17 km south of the Adelaide’s central business district owned and operated by the

I’m recommending you view a video presentation (can be accessed by clicking the link below) by A/Prof. David Paton which demonstrates the urgency of reforesting the region around Adelaide. Glenthorne is a 208-ha property 17 km south of the Adelaide’s central business district owned and operated by the