Rob Dietz over at the Centre for the Advancement of the Steady State Economy thought ConservationBytes.com readers would be interested in the following post by Tim Murray (the original post was entitled What if we stopped fighting for preservation and fought economic growth instead?). There are some interesting ideas here, and I concur that because we have failed to curtail extinctions, and there’s really no evidence that conservation biology alone will be enough to save what remains (despite 50 + years of development), big ideas like these are needed. I’d be interested to read your comments.

—

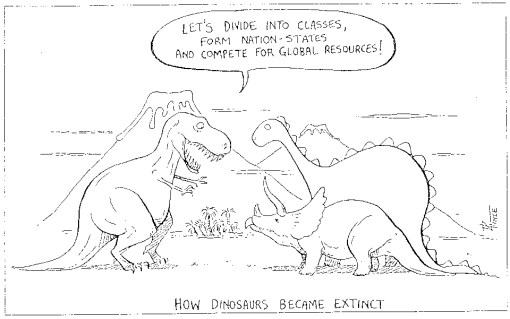

Each time environmentalists rally to defend an endangered habitat, and finally win the battle to designate it as a park “forever,” as Nature Conservancy puts it, the economic growth machine turns to surrounding lands and exploits them ever more intensively, causing more species loss than ever before, putting even more lands under threat. For each acre of land that comes under protection, two acres are developed, and 40% of all species lie outside of parks. Nature Conservancy Canada may indeed have “saved” – at least for now – two million acres [my addendum: that’s 809371 hectares], but many more millions have been ruined. And the ruin continues, until, once more, on a dozen other fronts, development comes knocking at the door of a forest, or a marsh or a valley that many hold sacred. Once again, environmentalists, fresh from an earlier conflict, drop everything to rally its defence, and once again, if they are lucky, yet another section of land is declared off-limits to logging, mining and exploration. They are like a fire brigade that never rests, running about, exhausted, trying to extinguish one brush fire after another, year after year, decade after decade, winning battles but losing the war.

Each time environmentalists rally to defend an endangered habitat, and finally win the battle to designate it as a park “forever,” as Nature Conservancy puts it, the economic growth machine turns to surrounding lands and exploits them ever more intensively, causing more species loss than ever before, putting even more lands under threat. For each acre of land that comes under protection, two acres are developed, and 40% of all species lie outside of parks. Nature Conservancy Canada may indeed have “saved” – at least for now – two million acres [my addendum: that’s 809371 hectares], but many more millions have been ruined. And the ruin continues, until, once more, on a dozen other fronts, development comes knocking at the door of a forest, or a marsh or a valley that many hold sacred. Once again, environmentalists, fresh from an earlier conflict, drop everything to rally its defence, and once again, if they are lucky, yet another section of land is declared off-limits to logging, mining and exploration. They are like a fire brigade that never rests, running about, exhausted, trying to extinguish one brush fire after another, year after year, decade after decade, winning battles but losing the war.

Despite occasional setbacks, the growth machine continues more furiously, and finally, even lands which had been set aside “forever” come under pressure. As development gets closer, the protected land becomes more valuable, and more costly to protect. Then government, under the duress of energy and resource shortages and the dire need for royalties and revenue, caves in to allow industry a foothold, then a chunk, then another. Yosemite Park, Hamber Provincial Park, Steve Irwin Park [my addendum – even the mention of this man is an insult to biodiversity conservation]… the list goes on. There is no durable sanctuary from economic growth. Any park that is made by legislation can be unmade by legislation. Governments change and so do circumstances. But growth continues and natural capital [my addendum: see my post on this term and others] shrinks. And things are not even desperate yet. Read the rest of this entry »

-34.917731

138.603034