A few months ago I was asked to do an online interview about ConservationBytes at The Reef Tank. I previously made mention of the interview (see post), but I think it’s time I reproduce it here.

A few months ago I was asked to do an online interview about ConservationBytes at The Reef Tank. I previously made mention of the interview (see post), but I think it’s time I reproduce it here.

The effects of pollution, carbon build up in the ocean, extinction, loss of coral reefs, over-fishing, and global warming is increasingly becoming more detrimental to our marine life and marine world.

Fortunately our marine ecosystems have Corey Bradshaw on their side. As a conservation ecologist, Corey studies these ecosystems with a passion, trying to understands the interactions between plants and animals that make up these ecosystems as well as what human activity is doing to them.

He has realised long ago that conservation and awareness is crucial to the survival of these living things and carries on the long tradition of studying and trying to understand these ecosystems at the School of Earth & Environmental Sciences at the University of Adelaide in South Australia.

He also avidly blogs about these pertinent issues at ConservationBytes.com, because he felt a need that these marine conservation issues needed to be heard. And he was more then right.

We were lucky enough to grab some time with Corey Bradshaw and he was kind enough to answer some important marine conservation questions, which are important in our desire: to make the marine world a better place.

What is your background in science and conservation?

I have a rather eclectic background in this area. I originally started my university education in general ecology, with a focus on plant ecology in particular (this was the strength of my undergraduate institution). There was no real emphasis on conservation per se until I started my postgraduate studies, although even then I was more interested in the empirical side of theoretical ecology than on conservation itself. It was more or less a gradual process that as I realised just how much we as a species have changed the planet in our (relatively) short time here, I became more and more dedicated to quantifying the links between species loss and how it affects human well-being.

After completing my MSc, PhD and first postdoctoral fellowship in New Zealand and Australia, I had the good fortune to work alongside a few excellent conservation ecologists specialising in extinction dynamics. This is where my mathematical bent and conservation interests really took off and eventually set the stage for most of my research today.

Your blog is ConservationBytes.com. Why the urge to start a blog on conservation only?

It may seem odd that I resisted blogging for many years because I thought it was a colossal time-waster that would take me away from my main scientific research. However, several things convinced me of its need and utility. First, it’s a wonderful vehicle to engage non-scientists about the research one does – let’s face it, most people don’t read scientific journals. Second, it’s interactive; people can ask questions or comment directly online. Third, it overcomes the strict language and technical rigour of most scientific publications and gets to the heart of the issue (it also allows me to express some opinions and speculations that are otherwise forbidden in scientific writing). Fourth, I realised there was a real lack of understanding about basic conservation science among the populace, so providing a vehicle for conservation science dissemination online appeared to be a good idea – there simply wasn’t anything like it when I started only a year ago. Finally, an effective, policy-changing scientist must advertise his/her research through the popular media to be recognised, so it obviously has career benefits.

Tell me about the conservation topics you cover?

ConservationBytes.com covers pretty much any topic that conforms to at least one of the following criteria:

-

It concerns research (previous, ongoing, planned) that is designed to improve the fate of biodiversity, whether locally, regionally or internationally

-

It concerns policy studies, actions or ideas that will have positive bearing on biodiversity conservation

-

It concerns demonstrations of the role biodiversity plays in providing humans with essential ecosystem services

I even have a section I call ‘Toothless’ that highlights ineffective conservation research or policy. Other areas include: exposés of well-known conservation scientists, a collection of links to conservation science journals, and my personal information (publications, CV, media attention).

What is your take on marine conservation? What does marine conservation include?

Given that I have worked in both marine and terrestrial realms from the tropics to the Antarctic, I really see little distinction in terms of conservation. True, the marine realm probably presents more challenges to conservation in some respects because it’s generally much more difficult and expensive to collect meaningful data, and it’s more difficult to control or mitigate people’s behaviour (especially in international waters), but the ecological patterns are the same (although I admit they may operate over different spatial and temporal scales).

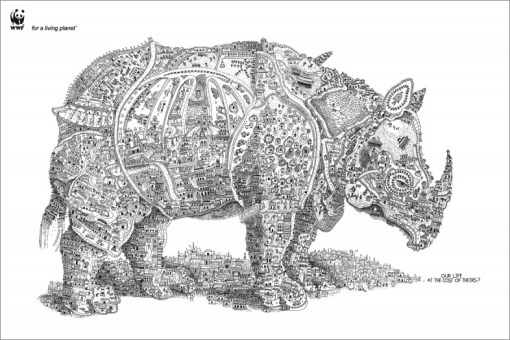

Current ‘hot’ topics in marine conservation include the global degradation and loss of coral reef ecosystems (and what to do about it), terrestrial run-off of pollutants and nutrients affecting marine communities, over-fishing and better fishing management strategies, the design of effective marine protected areas, the socio-economic implications of moving people away from direct exploitation to behaviours and economic activities that promote longer-term biological community stability and resilience, and of course, how climate change (via acidification, hypercapnia, temperature change, storm intensification, seal level rise and modified current structure) might exacerbate the systems that are already stressed by the aforementioned problems.

Have you done any work, research in the area of marine conservation?

Yes, quite a bit. Some salient areas include

-

The grey nurse shark Carcharias taurus was the world’s first shark species to receive legislative protection when the east Australian population was listed under the 1984 New South Wales Fisheries Management Act. It has since been listed as globally Vulnerable by the IUCN in 1996 and the east Australian population was declared Critically Endangered in 2003. Previously, we constructed deterministic, density-independent PVA models for the east Australian population that suggested dire prospects for its long-term persistence without direct and immediate intervention. However, deterministic models might be overly optimistic because they do not incorporate stochastic fluctuations that can drive small populations extinct, whereas failing to account for density feedback can predict overly pessimistic. We recently completed a study demonstrating that the most effective measure to reduce extinction risk was to legislate the mandatory use of offset circle hooks in both recreational and commercial fisheries. The increase in dedicated marine reserves and shift from bather protection nets to drumlines had much lower effectiveness.

-

The global extent of illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing is valued from US$10-23.5 billion per year, representing between 11 and 26 million tonnes of fish killed annually beyond legal commercial catches. In northern Australia, IUU fishing has advanced as a ‘protein-mining’ wave starting in the South China Sea in the 1970s and now penetrates consistently into the nation’s Exclusive Economic Zone. We have documented the extent of this wave and the implications for higher-order predators such as sharks, demonstrating that IUU fishing has already depleted large predators in Australian territorial waters. Given the negative relationship between IUU fishing takes and governance quality, we propose that deterring invading fishers will need substantially greater investment in border protection, and international accords to improve governance in neighbouring nations, if the tide of extinction is to be effectively mitigated.

-

Determining the extinction risk of the world’s shark and ray species – some work I’ve done recently with colleagues is to examine the patterns of shark biodiversity globally and determine which groups are most at risk of extinction. Not a surprise, but it turns out that the largest species of shark that reproduce the slowest are the most endangered (including all those bitey ones that frighten people).

-

Finally, I’m doing a lot of work now examining how the structure of coral reefs affects fish biodiversity patterns and long-term resilience. It turns out that basic biogeographic predictors (e.g., reef size and relative isolation from other reefs) really do dictate how temporally stable fish populations remain. And as we know, the more variable a population in time and space, the more likely it will go extinct (on average). The practical implication is that we can identify those coral reefs most likely to maintain their fish communities simply by measuring their size and position.

You’re from Australia, correct? What kind of marine conservation is going on there?

I’m originally from Canada, but I’ve spent most of my adult life in Australia (mostly in Tasmania, the Northern Territory, and now, Adelaide in South Australia). I did my PhD in the deep south of New Zealand (Otago University, Dunedin). In Australia, all the aforementioned ‘hot’ areas of marine conservation are in full swing, with greater and greater emphasis on climate change research. I think this aspect is pre-occupying most serious marine ecologists in Australia these days. For example, the southeast of Australia has already experienced some of the fastest warming in the Southern Hemisphere, with massive regional shifts in many species of fish, invertebrates, macroalgae and plankton.

What’s your take on ocean acidification? Do you think people need to be aware of this issue?

I used to believe ocean acidification was THE principal marine conservation issue facing us today, but now I think it’s just another stressor in a cornucopia of stressors. The main issue here is that we still understand so little of its implications for marine biodiversity. Sure, you lower the pH and up the partial CO2 (pCO2) of seawater, and many organisms don’t do so well (in terms of survival, reproduction and growth). However, it’s considerably more complex than this. pH and pCO2 vary substantially in space and time, and we have yet to quantify these patterns or how they are changing for most of the marine realm. Therefore, it’s difficult to simulate ‘real’ and future conditions in the lab.

Another issue is that temperature is changing must faster and so far exposure experiments indicate that it generally has a much more pronounced effect on marine organisms than acidification per se. However, like many climate change issues, a so-called ‘tipping point’ could be just around the corner that makes many marine communities collapse. It’s a frightening prospect, but one that needs a lot more dedicated research.

Can a person own an aquarium and still be considered a marine conservationist in your opinion?

Of course, provided one is cognisant of several important issues. First, most aquarists rely on the importation of non-native species. Lack of vigilance and carelessness has resulted in a suite of alien species being released into naïve ecosystems, resulting in the extinction or reduction of many native fish and invertebrates. Another issue is the transport cost – think how much carbon you are emitting by flying that tropical clownfish to your local pet shop in Norway. Third, do you know from which populations your displayed fish come? Were they harvested sustainably, or were they the last individuals plucked from a dying reef? A good knowledge of an animal’s origin is essential for the responsible aquarist. In my view one should play it safe. I think having aquaria filled with local species that are easily acquired, don’t cost the Earth to transport and pose no risk to native ecosystems is the most responsible way to go. You can also be a lot more certain of sustainable harvest if you live close by the source.

What is your take on climate change and its effect on marine life? Is being aware and educated on this particular topic and how it affects the marine world make someone a marine conservationist?

Awareness is only the first and most basic step. I’d say most of the world is ‘aware’ to some extent. It’s really the change in human behaviour that’s required before we make any true leaps forward. Some of the issues described above get to the heart of behavioural change. To use an analogy, it’s not enough to recognise that you’re an alcoholic, you have to stop drinking too to prevent the damage.

What can we do to raise awareness of the importance of marine conservation and conservation in general?

My personal take on this, and it applies to ALL biodiversity conservation (i.e., not just marine) is that people won’t take it seriously until they see how its loss affects their lives negatively. For example, let’s say we lose all commercially exploitable fish – not having access to delicious and healthy fish protein will mean people change the way fishing is done; that is, they’ll try to force fishers to fish sustainably and consumers to demand responsibly. The same can be said for more esoteric ecosystem services like carbon sequestration, oxygen production, water purification, pollination, waste detoxification, etc. if, and only if, we understand the economic and health benefits of keeping ecosystems intact. We need more research that makes the biodiversity-human benefit link so that people ultimately get the message. Destroying biodiversity means destroying yourself.

As I said before, awareness is only the first step.

As mentioned, quite a long analysis of the state of sharks worldwide. Bottom line? Well, as most of you might already know sharks aren’t doing too well worldwide, with around 52 % listed on the IUCN’s

As mentioned, quite a long analysis of the state of sharks worldwide. Bottom line? Well, as most of you might already know sharks aren’t doing too well worldwide, with around 52 % listed on the IUCN’s  In some ways this sort of goes against the notion that sharks are inherently more extinction-prone than other fish – a common motherhood statement seen at the beginning of almost all papers dealing with shark threats. What it does say though is that because sharks are on average larger and less fecund than your average fish, they tend to bounce back from declines more slowly, so they are more susceptible to rapid environmental change than your average fish. Guess what? We’re changing the environment pretty rapidly.

In some ways this sort of goes against the notion that sharks are inherently more extinction-prone than other fish – a common motherhood statement seen at the beginning of almost all papers dealing with shark threats. What it does say though is that because sharks are on average larger and less fecund than your average fish, they tend to bounce back from declines more slowly, so they are more susceptible to rapid environmental change than your average fish. Guess what? We’re changing the environment pretty rapidly.

A good friend and colleague of mine, Dr.

A good friend and colleague of mine, Dr.

Although buffalo in Australia experienced two major periods of population reduction since their introduction, a small proportion (estimated at ~ 20 %) escaped the BTEC reduction in the eastern part of its north Australian range. BTEC did not operate with uniformity across the entire range of buffalo, concentrating its destocking efforts in a general area from the western coast of the Northern Territory to west of the Mann River in Arnhem Land, and south roughly to Kakadu National Park’s southern border. Coincidently and not surprisingly, it is in this area that we observe most migration activity.

Although buffalo in Australia experienced two major periods of population reduction since their introduction, a small proportion (estimated at ~ 20 %) escaped the BTEC reduction in the eastern part of its north Australian range. BTEC did not operate with uniformity across the entire range of buffalo, concentrating its destocking efforts in a general area from the western coast of the Northern Territory to west of the Mann River in Arnhem Land, and south roughly to Kakadu National Park’s southern border. Coincidently and not surprisingly, it is in this area that we observe most migration activity.

This week a mate of mine was conferred her degree at the University of Adelaide and she invited me along to the graduation ceremony. Although academic graduation ceremonies can be a bit long and involve a little too much applause (in my opinion), I was fortunate enough to listen to the excellent and inspiring welcoming speech made by the University of Adelaide’s Dean of Science, Professor

This week a mate of mine was conferred her degree at the University of Adelaide and she invited me along to the graduation ceremony. Although academic graduation ceremonies can be a bit long and involve a little too much applause (in my opinion), I was fortunate enough to listen to the excellent and inspiring welcoming speech made by the University of Adelaide’s Dean of Science, Professor

A few months ago I was asked to do an online interview about

A few months ago I was asked to do an online interview about