Mention anything about ecosystem services – those ecological functions arising from the interactions between species that provide some benefit (source of food/clean water, health, etc.) to humanity1 – and one of the most cited examples is pollination.

Mention anything about ecosystem services – those ecological functions arising from the interactions between species that provide some benefit (source of food/clean water, health, etc.) to humanity1 – and one of the most cited examples is pollination.

It’s really a no-brainer, hence its popularity as an example. Pollinators (mainly insects, but birds, bats and other assorted species too) don’t exist to pollinate plants; rather, their principal source of food acquisition happens to spread around the gametes of the plants they regularly visit. Evolution has favoured the dependence of species in such ways because the mutualism benefits all involved, and in some cases, this dependence has become obligate. So when the habitats that pollinators need to survive are reduced or destroyed, inevitably their population sizes decline and the plants on which they feed lose their main sources of gene-spreading.

So what? Well, about 80 % of all wild plant species require insect pollinators for fruit and seed set, and about 75 % of all human crops require pollination by insects (mostly bees). So it’s pretty frightening to consider that although our global population is at 6.8 billion and growing rapidly, our main food pollinators (bees) are declining globally (see also previous post on bee declines). Indeed, domestic honey bee stocks have declined in the USA by 59 % since 1947 and in Europe by 25 % since 1985. Scared yet?

Another thing people don’t tend to get is that a bee cannot live on rapeseed alone. Most pollinators require intact forests to complete many of their other life history requirements (breeding, shelter, etc.) and merely forage occasionally in crop lands. Cut down all the adjacent bush, and your crops will suffer accordingly.

These, and other titbits to keep you awake at night and worry about what your grandchildren might eat are highlighted in a recent review in Trends in Ecology and Evolution by Potts and colleagues entitled Global pollinator declines: trends, impacts and drivers.

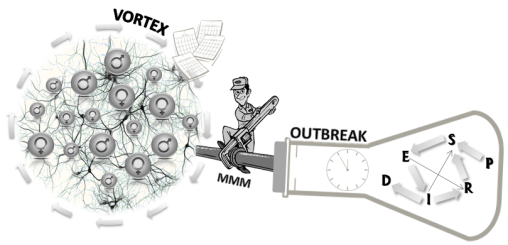

What’s driving all this loss? Several things, but it’s mainly due to ‘land-use change’ (a bullshit word people use generally to mean habitat loss, fragmentation and degradation). However, invasive species competition, pathogens and parasites, and climate change (and the synergies amongst all of these) are all contributing.

It always amazes me when people ask me why biodiversity is important. Despite the overwhelming knowledge we’ve accumulated about how functioning ecosystems make the planet liveable, despite it just being plainly stupid to think that humans are somehow removed from normal biological processes, and even with such in-your-face examples of global pollinator declines and the real, extremely worrying implication for food supplies, many people just don’t seem to get it. Every tree you cut down, every molecule of carbon dioxide you release, every drop of water you waste will punish you and your family directly for generations to come. How much more self-evident can you get?

Humanity seems to have a very poorly developed sense of self-preservation.

CJA Bradshaw

1It’s amazingly arrogant and anthropocentric to think of anything in ecosystems as ‘providing benefits to humanity’. After all, we’re just another species in a complex array of species within ecosystems – we just happen to be one of the numerically dominant ones, excel at ecosystem ‘engineering’ and as far as we know, are the only (semi-) sentient of the biologicals. Although the concept of ecosystem services is, I think, an essential abstraction to place emphasis on the importance of biodiversity conservation to the biodiversity ignorant, it does rub me a little the wrong way. It’s almost ascribing some sort of illogical religious perspective that the Earth was placed in its current form for our eventual benefit. We might be a fairly new species in geological time scales, but don’t think of ecosystems as mere provisions for our well-being.

Potts, S., Biesmeijer, J., Kremen, C., Neumann, P., Schweiger, O., & Kunin, W. (2010). Global pollinator declines: trends, impacts and drivers Trends in Ecology & Evolution DOI: 10.1016/j.tree.2010.01.007

Potts, S., Biesmeijer, J., Kremen, C., Neumann, P., Schweiger, O., & Kunin, W. (2010). Global pollinator declines: trends, impacts and drivers Trends in Ecology & Evolution DOI: 10.1016/j.tree.2010.01.007

-34.925770

138.599732