I’ve covered this sad state of affairs and one of Australia’s more notable biodiversity embarrassments over the last year (see Shocking continued loss of Australian mammals and Can we solve Australia’s mammal extinction crisis?), and now the most empirical demonstration of this is now published.

I’ve covered this sad state of affairs and one of Australia’s more notable biodiversity embarrassments over the last year (see Shocking continued loss of Australian mammals and Can we solve Australia’s mammal extinction crisis?), and now the most empirical demonstration of this is now published.

The biodiversity guru of Australia’s tropical north, John Woinarksi, has just published the definitive demonstration of the magnitude of mammal declines in Kakadu National Park (Australia’s largest national park, World Heritage Area, emblem of ‘co-management’ and supposed biodiversity and cultural jewel in Australia’s conservation crown). According to Woinarski and colleagues, most of those qualifiers are rubbish.

The paper published in Wildlife Research is entitled Monitoring indicates rapid and severe decline of native small mammals in Kakadu National Park, northern Australia and it concludes:

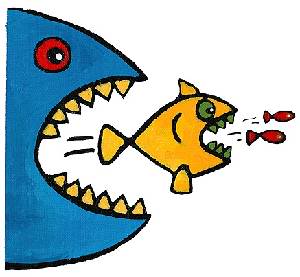

The native mammal fauna of Kakadu National Park is in rapid and severe decline. The cause(s) of this decline are not entirely clear, and may vary among species. The most plausible causes are too frequent fire, predation by feral cats and invasion by cane toads (affecting particularly one native mammal species).

I’ve done quite a bit of work in Kakadu myself, and the one thing that hits you every time you travel through it is the lack of visible wildlife. Sure, you’ll see horses, pigs and buffalo, as well as cane toads and cats, but getting a glimpse of anything native, from Conilurus to Varanus, and you’d consider yourself extremely lucky.

We’ve written a lot about the feral animal problem in Kakadu and even developed software tools to assist in density-reduction programmes. It doesn’t appear that anyone is listening.

Another gob-smacking vista you’ll get when travelling through Kakadu any time from April to December is that it’s either been burnt, actively burning or targeted for burning. They burn the shit out of the place every year. No wonder the native mammals are having such a hard time.

Combine all this with the dysfunctional management arrangement, and you cease to have a National Park. Kakadu is now a lifeless shell that does precious little for conservation of biodiversity (and 3 of the 5 criteria it had to satisfy to become a World Heritage Area are specifically related to natural resource ‘values’). I say, delist Kakadu now and let’s stop fooling ourselves.

Ok, back from the rant. Woinarski and others superimposed a mammal monitoring programme over top a fire-regime experiment for vegetation. Although they couldn’t sample every plot every season, they staggered the sampling to cover the area as best they could over the 13 years of monitoring (1996-2009). What they observed was staggering. Read the rest of this entry »

-34.925770

138.599732

Last week I mentioned that a group of us from Australia were travelling to Chicago to work with

Last week I mentioned that a group of us from Australia were travelling to Chicago to work with