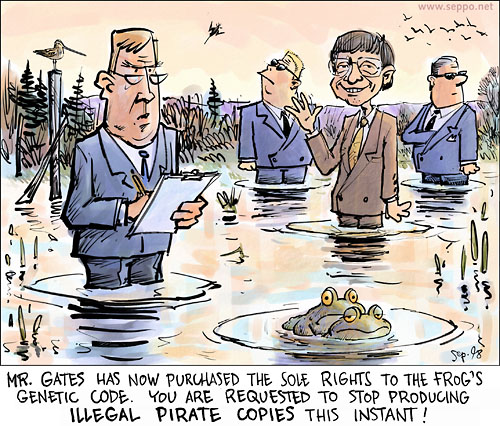

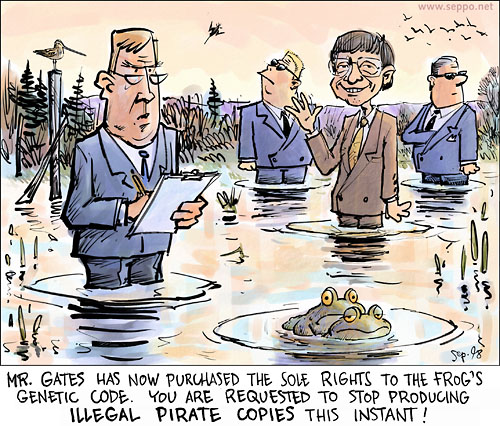

And the silliness continues…

See also full stock of previous ‘Cartoon guide to biodiversity loss’ compendia here.

Enjoy!

And the silliness continues…

See also full stock of previous ‘Cartoon guide to biodiversity loss’ compendia here.

Enjoy!

I just came across this little gem of a paper in Molecular Ecology (not, by any stretch, a common forum for biodiversity conservation-related papers). It’s another one of those wonderful little experimental manipulation studies I love so much (see previous examples here and here).

I just came across this little gem of a paper in Molecular Ecology (not, by any stretch, a common forum for biodiversity conservation-related papers). It’s another one of those wonderful little experimental manipulation studies I love so much (see previous examples here and here).

I’ve written a lot before about the loss of genetic diversity as a contributing factor to extinction risk, via things like Allee effects and inbreeding depression. I’ve also posted blurbs about our work and that of others on what makes particular species prone to become extinct or invasive (i.e., the two sides of the same evolutionary coin). Now Crawford and Whitney bring these two themes together in their paper entitled Population genetic diversity influences colonization success.

Yes, the evolved traits of a particular species will set it up either to do well or very badly under rapid environmental change, and invasive species tend to be those with rapid generation times, defence mechanisms, heightened dispersal capacity and rapid growth. However, such traits generally only predict a small amount in the variation in invasion success – the other being of course propagule pressure (a composite measure of the number of individuals of a non-native species [propagule size] introduced to a novel environment and the number of introduction events [propagule number] into the new host environment).

But, that’s not all. It turns out that just as reduced genetic diversity enhances a threatened species’ risk of extinction, so too does it reduce the ‘invasiveness’ of a weed. Using experimentally manipulated populations of the weedy herb Arabidopsis thaliana (mouse-ear cress; see if you get the joke), Crawford & Whitney measured greater population-level seedling emergence rates, biomass production, flowering duration and reproduction in high-diversity populations compared to lower-diversity ones. Maintain a high genetic diversity and your invasive species has a much higher potential to colonise a novel environment and spread throughout it.

Of course, this is related to propagule pressure because the more individuals that invade/are introduced the more times, the higher the likelihood that different genomes will be introduced as well. This is extremely important from a management perspective because it means that well-mixed (outbred) samples of invasive species probably can do a lot more damage to native biodiversity than a few, genetically similar individuals alone. Indeed, most introductions probably don’t result in a successful invasion mainly because they don’t have the genetic diversity to get over the hump of inbreeding depression in the first place.

The higher genetic (and therefore, phenotypic) variation in your pool of introduced individuals, the great the chance that at least a few will survive and proliferate. This is also a good bit of extra proof for our proposal that invasion and extinction are two sides of the same evolutionary coin.

![]() Crawford, K., & Whitney, K. (2010). Population genetic diversity influences colonization success Molecular Ecology DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2010.04550.x

Crawford, K., & Whitney, K. (2010). Population genetic diversity influences colonization success Molecular Ecology DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2010.04550.x

Bradshaw, C., Giam, X., Tan, H., Brook, B., & Sodhi, N. (2008). Threat or invasive status in legumes is related to opposite extremes of the same ecological and life-history attributes Journal of Ecology, 96, 869-883 DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2745.2008.01408.x

Hard to believe we’re already at Volume 3 – introducing the latest issue of Conservation Letters (Volume 3, Issue 1, February 2010). For full access, click here.

Note too we’ve jumped from 5 to 6 papers per issue. Congratulations to all our authors. Keep those submissions coming!

The much-touted Excellence in Research for Australia (ERA) initiative was established in 2008 to “…assesses research quality within Australia’s higher education institutions using a combination of indicators and expert review by committees comprising experienced, internationally-recognised experts”. Following on the heels of the United Kingdom’s Research Assessment Exercise (RAE) and Australia’s previous attempt at such a ranking (the now-defunct Research Quality Framework), we will now have a system that ranks research performance and universities in this country. Overall I think it’s a good thing so that the dead-wood can lift their game or go home, but no ranking system is perfect. Some well-deserving people will be left out in the cold.

The much-touted Excellence in Research for Australia (ERA) initiative was established in 2008 to “…assesses research quality within Australia’s higher education institutions using a combination of indicators and expert review by committees comprising experienced, internationally-recognised experts”. Following on the heels of the United Kingdom’s Research Assessment Exercise (RAE) and Australia’s previous attempt at such a ranking (the now-defunct Research Quality Framework), we will now have a system that ranks research performance and universities in this country. Overall I think it’s a good thing so that the dead-wood can lift their game or go home, but no ranking system is perfect. Some well-deserving people will be left out in the cold.

Opinions aside, I thought it would be useful to provide the ERA journal ranking categories in conservation and ecology for my readers, particularly for those in Australia. See also my Journals page for conservation journals, their impact factors and links. The ERA has ranked 20,712 unique peer-reviewed journals, with each given a single quality rating (or is not ranked). The ERA is careful to say that “A journal’s quality rating represents the overall quality of the journal. This is defined in terms of how it compares with other journals and should not be confused with its relevance or importance to a particular discipline.”.

They provide four tiers of quality rating:

If you’re an Australian conservation ecologist, then you’d be wise to target the higher-end journals for publication over the next few years (it will affect your rank).

So, here goes:

Conservation Journals

Ecology Journals (in addition to those listed above; only A* and A)

I’m sure I’ve missed a few, but that’ll cover most of the relevant journals. For the full, tortuous list of journals in Excel format, click here. Happy publishing!

As promised some time ago when I blogged about the imminent release of the book Conservation Biology for All (edited by Navjot Sodhi and Paul Ehrlich), I am now posting a few titbits from the book.

Today’s post is a blurb from Paul Ehrlich on the human population problem for conservation of biodiversity.

The size of the human population is approaching 7 billion people, and its most fundamental connection with conservation is simple: people compete with other animals., which unlike green plants cannot make their own food. At present Homo sapiens uses, coopts, or destroys close to half of all the food available to the rest of the animal kingdom. That means that, in essence, every human being added to the population means fewer individuals can be supported in the remaining fauna.

But human population growth does much more than simply cause a proportional decline in animal biodiversity – since as you know, we degrade nature in many ways besides competing with animals for food. Each additional person will have a disproportionate negative impact on biodiversity in general. The first farmers started farming the richest soils they could find and utilised the richest and most accessible resources first (Ehrlich & Ehrlich 2005). Now much of the soil that people first farmed has been eroded away or paved over, and agriculturalists increasingly are forced to turn to marginal land to grow more food.

Equally, deeper and poorer ore deposits must be mined and smelted today, water and petroleum must come from lower quality resources, deeper wells, or (for oil) from deep beneath the ocean and must be transported over longer distances, all at ever-greater environmental cost [my addition – this is exactly why we need to embrace the cheap, safe and carbon-free energy provided by nuclear energy].

The tasks of conservation biologists are made more difficult by human population growth, as is readily seen in the I=PAT equation (Holdren & Ehrlich 1974; Ehrlich & Ehrlich 1981). Impact (I) on biodiversity is not only a result of population size (P), but of that size multiplied by affluence (A) measured as per capita consumption, and that product multiplied by another factor (T), which summarises the technologies and socio-political-economic arrangements to service that consumption. More people surrounding a rainforest reserve in a poor nation often means more individuals invading the reserve to gather firewood or bush meat. More poeple in a rich country may mean more off-road vehicles (ORVs) assulting the biota – especially if the ORV manufacturers are politically powerful and can succesfully fight bans on their use. As poor countries’ populations grow and segments of them become more affluent, demand rises for meat and automobiles, with domesticated animals competing with or devouring native biota, cars causing all sorts of assults on biodiversity, and both adding to climate disruption. Globally, as a growing population demands greater quantities of plastics, industrial chemicals, pesticides, fertilisers, cosmetics, and medicines, the toxification of the planet escalates, bringing frightening problems for organisms ranging from polar bears to frogs (to say nothing of people!).

In sum, population growth (along with escalating consumption and the use of environmentally malign technologies) is a major driver of the ongoing destruction of populations, species, and communities that is a salient feature of the Anthropocene. Humanity , as the dominant animal (Ehrlich & Ehrlich 2008), simply out competes other animals for the planet’s productivity, and often both plants and animals for its freshwater. While dealing with more limited problems, it therefore behoves every conservation biologist to put part of her time into restraining those drivers, including working to humanely lower [sic] birth rates until population growth stops and begins a slow decline twoard a sustainable size (Daily et al. 1994).

Incidentally, Paul Ehrlich is travelling to Adelaide this year (November 2010) for some high-profile talks and meetings. Stay tuned for coverage of the events.

Patrick McGoohan in his role as the less-than-sentimental King Edward ‘Longshanks’ in the 1995 production of ‘Braveheart’ said it best in his references to the invocation of ius primæ noctis:

What a charmer.

Dabbling in molecular ecology myself over the past few years with some gel-jockey types (e.g., Dick Frankham [author of Introduction to Conservation Genetics], Melanie Lancaster, Paul Sunnucks, Yuji Isagi inter alios), I’m quite fascinated by the application of good molecular techniques in conservation biology. So when I came across the paper by Fitzpatrick and colleagues entitled Rapid spread of invasive genes into a threatened native species in PNAS, I was quite pleased.

When people usually think about invasive species, they tend to think ‘predator eating naïve native prey’ or ‘weed outcompeting native plant’. These are all big problems (e.g., think feral cats in Australia or knapweed in the USA), but what people probably don’t think about is the insidious concept of ‘genomic extinction’. This is essentially a congener invasive species breeding with a native one, thus ‘diluting’ the native’s genome until it no longer resembles its former self. A veritable case of ‘breeding them out’.

Who cares if at least some of the original genome remains? Some would argue that ‘biodiversity’ should be measured in terms of genetic diversity, not just species richness (I tend to agree), so any loss of genes is a loss of biodiversity. Perhaps more practically, hybridisation can lead to reduced fitness, like we observed in hybridised fur seals on Macquarie Island.

Fitzpatrick and colleagues measured the introgression of alleles from the deliberately introduced barred tiger salamander (Ambystoma tigrinum mavortium) into threatened California tiger salamanders (A. californiense) out from the initial introduction site. While most invasive alleles neatly stopped appearing in sampled salamanders not far from the introduction site, three invasive alleles persisted up to 100 km from the introduction site. Not only was the distance remarkable for such a small, non-dispersing beastie, the rate of introgression was much faster than would be expected by chance (60 years), suggesting selection rather than passive genetic drift. Almost none of the native alleles persisted in the face of the three super-aggressive invasive alleles.

The authors claim that the effects on native salamander fitness are complex and it would probably be premature to claim that the introgression is contributing to their threatened status, but they do raise an important management conundrum. If species identification rests on the characterisation of a specific genome, then none of the native salamanders would qualify for protection under the USA’s Endangered Species Act. They believe then that so-called ‘genetic purity’ is an impractical conservation goal, but it can be used to shield remaining ‘mostly native’ populations from further introgression.

Nice study.

![]() Fitzpatrick, B., Johnson, J., Kump, D., Smith, J., Voss, S., & Shaffer, H. (2010). Rapid spread of invasive genes into a threatened native species Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0911802107

Fitzpatrick, B., Johnson, J., Kump, D., Smith, J., Voss, S., & Shaffer, H. (2010). Rapid spread of invasive genes into a threatened native species Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0911802107

Lancaster, M., Bradshaw, C.J.A., Goldsworthy, S.D., & Sunnucks, P. (2007). Lower reproductive success in hybrid fur seal males indicates fitness costs to hybridization Molecular Ecology, 16 (15), 3187-3197 DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03339.x

A little bit of conservation wisdom for you this weekend.

In last week’s issue of Nature, well-known conservation planner and all-round smart bloke, Reed Noss (who just happens to be an editor for Conservation Letters and Conservation Biology), provided some words of extreme wisdom. Not pulling any punches in his Correspondence piece entitled Local priorities can be too parochial for biodiversity, Noss essentially says ‘don’t leave the important biodiversity decisions to the locals’.

He argues rather strongly in his response to Smith and colleagues’ opinion piece (Let the locals lead) that local administrators just can’t be trusted to make good conservation decisions given their focus on local economic development and other political imperatives. He basically says that the big planning decisions should be made at grander scales that over-ride local concerns because, well, the big fish in their little ponds can’t be trusted (nor do they have the training) to do what’s best for regional biodiversity conservation.

I couldn’t agree more – he states:

“Academic researchers, conservation non-governmental organizations and other ‘foreign’ interests tend to be better informed, less subject to local political influence and more experienced in conservation planning than local agencies.”

Of course, being part of the first group, I’m probably a little biased, but I dare say that we’ve got a lot better handle on the science beyond saving biodiversity, as well as a better understanding of why that’s important, than your average regional representative, village council, chief, Lord Mayor or state member. Sure, ‘engage your stakeholders’ (I have images of shooting missiles at people holding star pickets with this gem of business jargon wankery, but there you go), but please base the decision on science first. I think Smith and colleagues have some good points, but I am more in favour of a broad-scale benevolent dictatorship in conservation planning than fine-scale democracy. Granted, the best formula is likely to be very context-specific, and of course, you need some people with local implementation power to make it happen.

Dear Honourable Minister, you may sign on the dotted line to make policy real, but please, please listen to us before you do. Your very life and those of your children depend on it.

![]() Noss, R. (2010). Local priorities can be too parochial for biodiversity Nature, 463 (7280), 424-424 DOI: 10.1038/463424a

Noss, R. (2010). Local priorities can be too parochial for biodiversity Nature, 463 (7280), 424-424 DOI: 10.1038/463424a

Smith, R., Veríssimo, D., Leader-Williams, N., Cowling, R., & Knight, A. (2009). Let the locals lead Nature, 462 (7271), 280-281 DOI: 10.1038/462280a

A short post about a small letter that recently appeared in the latest issue of Conservation Biology – the dangers of REDD.

REDD. What is it? The acronym for ‘Reduced Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation’, it is the idea of providing financial incentives to developing countries to reduce forest clearance by paying them to keep them standing. It should work because of the avoided carbon emissions that can be gained from keeping forests intact. Hell, we certainly need it given the biodiversity crisis arising mainly from deforestation occurring in much of the (largely tropical) developing world. The idea is that someone pollutes, buys carbon credits that are then paid to some developing nation to prevent more forest clearance, and then biodiversity gets a helping hand in the process. It’s essentially carbon trading with an added bonus. Nice idea, but difficult to implement for a host of reasons that I won’t go into here (but see Miles & Kapos Science 2008 & Busch et al. 2009 Environ Res Lett).

Venter and colleagues in their letter entitled Avoiding Unintended Outcomes from REDD now warn us about another potential hazard of REDD that needs some pretty quick thinking and clever political manoeuvring to avoid.

While REDD is a good idea and I support it fully with carefully designed implementation, Venter and colleagues say that without good monitoring data and some well-planned immediate policy implementation, there could be a rush to clear even more forest area in the short term.

Essentially they argue that when the Kyoto Protocol expires in 2012, there could be a 2-year gap when forest loss would not be counted against carbon payments, and its in this window that countries might fell forests and expand agriculture before REDD takes effect (i.e., clear now and avoid later penalties).

How do we avoid this? The authors suggest that the implementation of policies to reward early efforts to reduce forest clearance and to penalise those who rush to do early clearing need to be put in place NOW. Rewards could take the form of credits, and penalties could be something like the annulment of future REDD discounts. Of course, to achieve any of this you have to know who’s doing well and who’s playing silly buggers, which means good forest monitoring. Satellite imagery analysis is probably key here.

CJA Bradshaw

![]() Oscar Venter, James E.M. Watson, Erik Meijaard, William F. Laurance, & Hugh P. Possingham (2010). Avoiding Unintended Outcomes from REDD Conservation Biology, 24 (1), 5-6 DOI: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2009.01391.x

Oscar Venter, James E.M. Watson, Erik Meijaard, William F. Laurance, & Hugh P. Possingham (2010). Avoiding Unintended Outcomes from REDD Conservation Biology, 24 (1), 5-6 DOI: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2009.01391.x

Alternate title: When pigs fly and fish say ‘hi’.

Alternate title: When pigs fly and fish say ‘hi’.

I’m covering a quick little review of a paper just published online in Fish and Fisheries about the two chances Europe has of meeting its legal obligations of rebuilding its North East Atlantic fish stocks by 2015 (i.e., Buckley’s and none).

The paper entitled Rebuilding fish stocks no later than 2015: will Europe meet the deadline? by Froese & Proelß describes briefly the likelihood Europe will meet the obligations set out under the United Nations’ Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) of “maintaining or restoring fish stocks at levels that are capable of producing maximum sustainable yield” by 2015 as set out in the Johannesburg Plan of Implementation of 2002.

Using fish stock assessment data and several criteria (3 methods for estimating maximum sustainable yield [MSY], 3 methods for estimating fishing mortality [Fmsy] & 2 methods for estimating spawning biomass [Bmsy]), they conclude that 49 (91 %) of the examined European stocks will fail to meet the goal under a ‘business as usual’ scenario.

The upshot is that European fisheries authorities have been and continue to set their total allowable catches (TACs) too high. We’ve seen this before with Atlantic bluefin tuna and the International Conspiracy to Catch All Tunas. Seems like most populations of exploited fishes are in fact in the same boat (quite literally!).

It’s amazing, really, the lack of ‘political will’ in fisheries – driving your source of income into oblivion doesn’t seem to register in the short-sighted vision of those earning their associated living or those supposedly looking out for their long-term interests.

![]() Froese, R., & Proelß, A. (2010). Rebuilding fish stocks no later than 2015: will Europe meet the deadline? Fish and Fisheries DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-2979.2009.00349.x

Froese, R., & Proelß, A. (2010). Rebuilding fish stocks no later than 2015: will Europe meet the deadline? Fish and Fisheries DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-2979.2009.00349.x

Pitcher, T., Kalikoski, D., Pramod, G., & Short, K. (2009). Not honouring the code Nature, 457 (7230), 658-659 DOI: 10.1038/457658a

I’m off for a long weekend at the beach, so I decided to keep this short. My post concerns the upcoming (well, July 2010) 24th International Congress for Conservation Biology (Society for Conservation Biology – SCB) to be held in Edmonton, Canada from 3-7 July 2010. I hadn’t originally planned on attending, but I’ve changed my mind and will most certainly be giving a few talks there.

I’m off for a long weekend at the beach, so I decided to keep this short. My post concerns the upcoming (well, July 2010) 24th International Congress for Conservation Biology (Society for Conservation Biology – SCB) to be held in Edmonton, Canada from 3-7 July 2010. I hadn’t originally planned on attending, but I’ve changed my mind and will most certainly be giving a few talks there.

There’s not much to report yet, apart from the abstract submission deadline looming next week (20 January). If you plan on submitting an abstract, get it in now (I’m rushing too). Actual registration opens online on 15 February.

The conference’s theme is “Conservation for a Changing Planet” – well, you can’t get much more topical (and general) than that! The conference website states:

Humans are causing large changes to the ecology of the earth. Industrial development and agriculture are changing landscapes. Carbon emissions to the atmosphere are changing climates. Nowhere on earth are changes to climate having more drastic effects on ecosystems and human cultures than in the north. Circumpolar caribou and reindeer populations are declining with huge consequences for indigenous peoples of the north, motivating our use of caribou in the conference logo. Developing conservation strategies to cope with our changing planet is arguably the greatest challenge facing today’s world and its biodiversity.

Sort of hits home in a personal way for me – I did my MSc on caribou populations in northern Canada a long time before getting into conservation biology proper (see example papers: Woodland caribou relative to landscape patterns in northeastern Alberta, Effects of petroleum exploration on woodland caribou in Northeastern Alberta & Winter peatland habitat selection by woodland caribou in northeastern Alberta), and we’ve recently published a major review on the boreal ecosystem.

Only 3 plenary speakers listed so far: David Schindler, Shane Mahoney and Georgina Mace (the latter being a featured Conservation Scholar here on ConservationBytes.com). I’m particularly looking forward to Georgina’s presentation. I’ll hopefully be able to blog some of the presentations while there. If you plan on attending, please come up and say hello!

Many non-Australians might not know it, but Australia is overrun with feral vertebrates (not to mention weeds and invertebrates). We have millions of pigs, dogs, camels, goats, buffalo, deer, rabbits, cats, foxes and toads (to name a few). In a continent that separated from Gondwana about 80 million years ago, this allowed a fairly unique biota to evolve, such that when Aboriginals and later, Europeans, started introducing all these non-native species, it quickly became an ecological disaster. One of my first posts here on ConservationBytes.com was in fact about feral animals. Since then, I’ve written quite a bit on invasive species, especially with respect to mammal declines (see Few people, many threats – Australia’s biodiversity shame, Shocking continued loss of Australian mammals, Can we solve Australia’s mammal extinction crisis?).

Many non-Australians might not know it, but Australia is overrun with feral vertebrates (not to mention weeds and invertebrates). We have millions of pigs, dogs, camels, goats, buffalo, deer, rabbits, cats, foxes and toads (to name a few). In a continent that separated from Gondwana about 80 million years ago, this allowed a fairly unique biota to evolve, such that when Aboriginals and later, Europeans, started introducing all these non-native species, it quickly became an ecological disaster. One of my first posts here on ConservationBytes.com was in fact about feral animals. Since then, I’ve written quite a bit on invasive species, especially with respect to mammal declines (see Few people, many threats – Australia’s biodiversity shame, Shocking continued loss of Australian mammals, Can we solve Australia’s mammal extinction crisis?).

So you can imagine that we do try to find the best ways to reduce the damage these species cause; unfortunately, we tend to waste a lot of money because density reduction culling programmes aren’t usually done with much forethought, organisation or associated research. A case in point – swamp buffalo were killed in vast numbers in northern Australia in the 1980s and 1990s, but now they’re back with a vengeance.

Enter S.T.A.R. – the clumsily named ‘Spatio-Temporal Animal Reduction’ [model] that we’ve just published in Methods in Ecology and Evolution (title: Spatially explicit spreadsheet modelling for optimising the efficiency of reducing invasive animal density by CR McMahon and colleagues).

Enter S.T.A.R. – the clumsily named ‘Spatio-Temporal Animal Reduction’ [model] that we’ve just published in Methods in Ecology and Evolution (title: Spatially explicit spreadsheet modelling for optimising the efficiency of reducing invasive animal density by CR McMahon and colleagues).

This little Excel-based spreadsheet model is designed specifically to optimise the culling strategies for feral pigs, buffalo and horses in Kakadu National Park (northern Australia), but our aim was to make it easy enough to use and modify so that it could be applied to any invasive species anywhere (ok, admittedly it would work best for macro-vertebrates).

The application works on a grid of habitat types, each with their own carrying capacities for each species. We then assume some fairly basic density-feedback population models and allow animals to move among cells. We then hit them virtually with a proportional culling rate (which includes a hunting-efficiency feedback), and estimate the costs associated with each level of kill. The final outputs give density maps and graphs of the population trajectory.

The application works on a grid of habitat types, each with their own carrying capacities for each species. We then assume some fairly basic density-feedback population models and allow animals to move among cells. We then hit them virtually with a proportional culling rate (which includes a hunting-efficiency feedback), and estimate the costs associated with each level of kill. The final outputs give density maps and graphs of the population trajectory.

We’ve added a lot of little features to maximise flexibility, including adjusting carrying capacities, movement rates, operating costs and overheads, and proportional harvest rates. The user can also get some basic sensitivity analyses done, or do district-specific culls. Finally, we’ve included three optimisation routines that estimate the best allocation of killing effort, for both maximising density reduction or working to a specific budget, and within a spatial or non-spatial context.

Our hope is that wildlife managers responsible for safeguarding the biodiversity of places like Kakadu National Park actually use this tool to maximise their efficiency. Kakadu has a particularly nasty set of invasive species, so it’s important those in charge get it right. So far, they haven’t been doing too well.

You can download the Excel program itself here (click here for the raw VBA code), and the User Manual is available here. Happy virtual killing!

P.S. If you’re concerned about animal welfare issues associated with all this, I invite you to read one of our recent papers on the subject: Convergence of culture, ecology and ethics: management of feral swamp buffalo in northern Australia.

![]() C.R. McMahon, B.W. Brook,, N. Collier, & C.J.A. Bradshaw (2010). Spatially explicit spreadsheet modelling for optimising the efficiency of reducing invasive animal density Methods in Ecology and Evolution : 10.1111/j.2041-210X.2009.00002.x

C.R. McMahon, B.W. Brook,, N. Collier, & C.J.A. Bradshaw (2010). Spatially explicit spreadsheet modelling for optimising the efficiency of reducing invasive animal density Methods in Ecology and Evolution : 10.1111/j.2041-210X.2009.00002.x

Albrecht, G., McMahon, C., Bowman, D., & Bradshaw, C. (2009). Convergence of Culture, Ecology, and Ethics: Management of Feral Swamp Buffalo in Northern Australia Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics, 22 (4), 361-378 DOI: 10.1007/s10806-009-9158-5

Bradshaw, C., Field, I., Bowman, D., Haynes, C., & Brook, B. (2007). Current and future threats from non-indigenous animal species in northern Australia: a spotlight on World Heritage Area Kakadu National Park Wildlife Research, 34 (6) DOI: 10.1071/WR06056

In keeping with the theme of extinctions from my last post, I want to highlight a paper we’ve recently had published online early in Ecology entitled Limited evidence for the demographic Allee effect from numerous species across taxa by Stephen Gregory and colleagues. This one is all about Allee effects – well, it’s all about how difficult it is to find them!

Now, the evidence for component Allee effects abounds, but finding real instances of reduced population growth rate at low population sizes is difficult. And this is really what we should be focussing on in conservation biology – a lower-than-expected growth rate at low population sizes means that recovery efforts for rare and endangered species must be stepped up considerably because their rebound potential is lower than it should be.

We therefore queried over 1000 time series of abundance from many different species and lo and behold, the evidence for that little dip in population growth rate at low densities was indeed rare – about 1 % of all time series examined!

I suppose this isn’t that surprising, but what was interesting was that this didn’t depend on sample size (time series where Allee models had highest support were in fact shorter) or variability (they were also less variable). All this seems a little counter-intuitive, but it gels with what’s been assumed or hypothesised before. Measurement error, climate variability and the sheer paucity of low-abundance time series makes their detection difficult. Nonetheless, for those series showing demographic Allee effects, their relative model support was around 12%, suggesting that such density feedback might influence the population growth rate of just over 1 in 10 natural populations. In fact, the many problems with density feedback detections in time series that load toward negative feedback (sometimes spuriously) suggest that even our small sample of Allee time series are probably vastly underestimated. We have pretty firm evidence that inbreeding is prevalent in threatened species, and demographic Allee effects are the mechanism by which such depression can lead a population down the extinction vortex.

![]() Gregory, S., Bradshaw, C.J.A., Brook, B.W., & Courchamp, F. (2009). Limited evidence for the demographic Allee effect from numerous species across taxa Ecology DOI: 10.1890/09-1128

Gregory, S., Bradshaw, C.J.A., Brook, B.W., & Courchamp, F. (2009). Limited evidence for the demographic Allee effect from numerous species across taxa Ecology DOI: 10.1890/09-1128

Not an easy task, measuring extinction. For the most part, we must use techniques to estimate extinction rates because, well, it’s just bloody difficult to observe when (and where) the last few individuals in a population finally kark it. Even Fagan & Holmes’ exhaustive search of extinction time series only came up with 12 populations – not really a lot to go on. It’s also nearly impossible to observe species going extinct if they haven’t even been identified yet (and yes, probably still the majority of the world’s species – mainly small, microscopic or subsurface species – have yet to be identified).

So conservation biologists do other things to get a handle on the rates, relying mainly on the species-area relationship (SAR), projecting from threatened species lists, modelling co-extinctions (if a ‘host’ species goes extinct, then its obligate symbiont must also) or projecting declining species distributions from climate envelope models.

But of course, these are all estimates and difficult to validate. Enter a nice little review article recently published online in Biodiversity and Conservation by Nigel Stork entitled Re-assessing current extinction rates which looks at the state of the art and how the predictions mesh with the empirical data. Suffice it to say, there is a mismatch.

Stork writes that the ‘average’ estimate of losing about 100 species per day has hardly any empirical support (not surprising); only about 1200 extinctions have been recorded in the last 400 years. So why is this the case?

As mentioned above, it’s difficult to observe true extinction because of the sampling issue (the rarer the individuals, the more difficult it is to find them). He does cite some other problems too – the ‘living dead‘ concept where species linger on for decades, perhaps longer, even though their essential habitat has been destroyed, forest regrowth buffering some species that would have otherwise been predicted to go extinct under SAR models, and differing extinction proneness among species (I’ve blogged on this before).

Of course, we could just all be just a pack of doomsday wankers vainly predicting the end of the world ;-)

Well, I think not – if anything, Stork concludes that it’s all probably worse than we currently predict because of extinction synergies (see previous post about this concept) and the mounting impact of rapid global climate change. If anything, the “100 species/day” estimate could look like a utopian ideal in a few hundred years. I do disagree with Stork on one issue though – he claims that deforestation isn’t probably as bad as we make it out. I’d say the opposite (see here, here & here) – we know so little of how tropical forests in particular function that I dare say we’ve only just started measuring the tip of the iceberg.

![]() Stork, N. (2009). Re-assessing current extinction rates Biodiversity and Conservation DOI: 10.1007/s10531-009-9761-9

Stork, N. (2009). Re-assessing current extinction rates Biodiversity and Conservation DOI: 10.1007/s10531-009-9761-9

A new book that I’m proud to have had a hand in writing is just about to come out with Oxford University Press called Conservation Biology for All. Edited by the venerable Conservation Scholars, Professors Navjot Sodhi (National University of Singapore) and Paul Ehrlich (Stanford University), it’s a powerhouse of some of the world’s leaders in conservation science and application.

A new book that I’m proud to have had a hand in writing is just about to come out with Oxford University Press called Conservation Biology for All. Edited by the venerable Conservation Scholars, Professors Navjot Sodhi (National University of Singapore) and Paul Ehrlich (Stanford University), it’s a powerhouse of some of the world’s leaders in conservation science and application.

The book strives to “…provide cutting-edge but basic conservation science to a global readership”. In short, it’s written to bring the forefront of conservation science to the general public, with OUP promising to make it freely available online within about a year from its release in early 2010 (or so the rumour goes). The main idea here is that those in most need of such a book – the conservationists in developing nations – can access the wealth of information therein without having to sacrifice the village cow to buy it.

I won’t go into any great detail about the book’s contents (mainly because I have yet to receive my own copy and read most of the chapters!), but I have perused early versions of Kevin Gaston‘s excellent chapter on biodiversity, and Tom Brook‘s overview of conservation planning and prioritisation. Our chapter (Chapter 16 by Barry Brook and me), is an overview of statistical and modelling philosophy and application with emphasis on conservation mathematics. It’s by no means a complete treatment, but it’s something we want to develop further down the track. I do hope many people find it useful.

I’ve reproduced the chapter title line-up below, with links to each of the authors websites.

As you can see, it’s a pretty impressive collection of conservation stars and hard-hitting topics. Can’t wait to get my own copy! I will probably blog individual chapters down the track, so stay tuned.

I’ve decided to blog this a little earlier than I would usually simply because the COP15 is still fresh in everyone’s minds and the paper is now online as an ‘Accepted Article’, so it is fully citable.

I’ve decided to blog this a little earlier than I would usually simply because the COP15 is still fresh in everyone’s minds and the paper is now online as an ‘Accepted Article’, so it is fully citable.

The paper published in Conservation Letters by Strassburg and colleagues is entitled Global congruence of carbon storage and biodiversity in terrestrial ecosystems is noteworthy because it provides a very useful answer to a very basic question. If one were to protect natural habitats based on their carbon storage potential, would one also be protecting the most biodiversity (and of course, vice versa)?

Turns out, one would.

Using a global dataset of ~ 20,000 species of mammal, bird and amphibian, they compared three indices of biodiversity distribution (species richness, species threat & range-size rarity) to a new global above- and below-ground carbon biomass dataset. It turns out that at least for species richness, the correlations were fairly strong (0.8-ish, with some due to spatial autocorrelation); for threat and rarity indices, the correlations were rather weaker (~0.3-ish).

So what does this all mean for policy? Biodiversity hotspots – those areas around the globe with the highest biodiversity and greatest threats – have some of the greatest potential to store carbon as well as guard against massive extinctions if we prioritise them for conservation. Places such as the Amazon, Borneo Sumatra and New Guinea definitely fall within this category.

However, not all biodiversity hotspots are created equal; areas such as Brazil’s Cerrado or the savannas of the Rift Valley in East Africa have relatively lower carbon storage, and so carbon-trading schemes wouldn’t necessarily do much for biodiversity in these areas.

The overall upshot is that we should continue to pursue carbon-trading schemes such as REDD (Reduced Emissions from Deforestation and forest Degradation) because they will benefit biodiversity (contrary to what certain ‘green’ organisations say about it), but we can’t sit back and hope that REDD will solve all of biodiversity’s problems world wide.

![]() Strassburg, B., Kelly, A., Balmford, A., Davies, R., Gibbs, H., Lovett, A., Miles, L., Orme, C., Price, J., Turner, R., & Rodrigues, A. (2009). Global congruence of carbon storage and biodiversity in terrestrial ecosystems Conservation Letters DOI: 10.1111/j.1755-263X.2009.00092.x

Strassburg, B., Kelly, A., Balmford, A., Davies, R., Gibbs, H., Lovett, A., Miles, L., Orme, C., Price, J., Turner, R., & Rodrigues, A. (2009). Global congruence of carbon storage and biodiversity in terrestrial ecosystems Conservation Letters DOI: 10.1111/j.1755-263X.2009.00092.x

Although I’ve already blogged about our recent paper in Biological Conservation on minimum viable population sizes, American Scientist just did a great little article on the paper and concept that I’ll share with you here:

Although I’ve already blogged about our recent paper in Biological Conservation on minimum viable population sizes, American Scientist just did a great little article on the paper and concept that I’ll share with you here:

Imagine how useful it would be if someone calculated the minimum population needed to preserve each threatened organism on Earth, especially in this age of accelerated extinctions.

A group of Australian researchers say they have nailed the best figure achievable with the available data: 5,000 adults. That’s right, that many, for mammals, amphibians, insects, plants and the rest.

Their goal wasn’t a target for temporary survival. Instead they set the bar much higher, aiming for a census that would allow a species to pursue a standard evolutionary lifespan, which can vary from one to 10 million years.

That sort of longevity requires abundance sufficient for a species to thrive despite significant obstacles, including random variation in sex ratios or birth and death rates, natural catastrophes and habitat decline. It also requires enough genetic variation to allow adequate amounts of beneficial mutations to emerge and spread within a populace.

“We have suggested that a major rethink is required on how we assign relative risk to a species,” says conservation biologist Lochran Traill of the University of Adelaide, lead author of a Biological Conservation paper describing the projection.

Conservation biologists already have plenty on their minds these days. Many have concluded that if current rates of species loss continue worldwide, Earth will face a mass extinction comparable to the five big extinction events documented in the past. This one would differ, however, because it would be driven by the destructive growth of one species: us.

More than 17,000 of the 47,677 species assessed for vulnerability of extinction are threatened, according to the latest Red List of Threatened Species prepared by the International Union for Conservation of Nature. That includes 21 percent of known mammals, 30 percent of known amphibians, 12 percent of known birds and 70 percent of known plants. The populations of some critically endangered species number in the hundreds, not thousands.

In an effort to help guide rescue efforts, Traill and colleagues, who include conservation biologists and a geneticist, have been exploring minimum viable population size over the past few years. Previously they completed a meta-analysis of hundreds of studies considering such estimates and concluded that a minimum head count of more than a few thousand individuals would be needed to achieve a viable population.

“We don’t have the time and resources to attend to finding thresholds for all threatened species, thus the need for a generalization that can be implemented across taxa to prevent extinction,” Traill says.

In their most recent research they used computer models to simulate what population numbers would be required to achieve long-term persistence for 1,198 different species. A minimum population of 500 could guard against inbreeding, they conclude. But for a shot at truly long-term, evolutionary success, 5,000 is the most parsimonious number, with some species likely to hit the sweet spot with slightly less or slightly more.

“The practical implications are simply that we’re not doing enough, and that many existing targets will not suffice,” Traill says, noting that many conservation programs may inadvertently be managing protected populations for extinction by settling for lower population goals.

The prospect that one number, give or take a few, would equal the minimum viable population across taxa doesn’t seem likely to Steven Beissinger, a conservation biologist at the University of California at Berkeley.

“I can’t imagine 5,000 being a meaningful number for both Alabama beach mice and the California condors. They are such different organisms,” Beissinger says.

Many variables must be considered when assessing the population needs of a given threatened species, he says. “This issue really has to do with threats more than stochastic demography. Take the same rates of reproduction and survival and put them in a healthy environment and your minimum population would be different than in an environment of excess predation, loss of habitat or effects from invasive species.”

But, Beissinger says, Traill’s group is correct for thinking that conservation biologists don’t always have enough empirically based standards to guide conservation efforts or to obtain support for those efforts from policy makers.

“One of the positive things here is that we do need some clear standards. It might not be establishing a required number of individuals. But it could be clearer policy guidelines for acceptable risks and for how many years into the future can we accept a level of risk,” Beissinger says. “Policy people do want that kind of guidance.”

Traill sees policy implications in his group’s conclusions. Having a numerical threshold could add more precision to specific conservation efforts, he says, including stabs at reversing the habitat decline or human harvesting that threaten a given species.

“We need to restore once-abundant populations to the minimum threshold,” Traill says. “In many cases it will make more economic and conservation sense to abandon hopeless-case species in favor of greater returns elsewhere.

Another great line-up in Conservation Letters‘ last issue for 2009. For full access, click here.

Today’s post covers a neat little review just published online in Conservation Letters by Feagin and colleagues entitled Shelter from the storm? Use and misuse of coastal vegetation bioshields for managing natural disasters. I’m covering this for three reasons: (1) it’s a great summary and wake-up call for those contemplating changing coastal ecosystems in the name of disaster management, (2) I have a professional interest in the ecosystem integrity-disaster interface and (3) I had the pleasure of editing this article.

Today’s post covers a neat little review just published online in Conservation Letters by Feagin and colleagues entitled Shelter from the storm? Use and misuse of coastal vegetation bioshields for managing natural disasters. I’m covering this for three reasons: (1) it’s a great summary and wake-up call for those contemplating changing coastal ecosystems in the name of disaster management, (2) I have a professional interest in the ecosystem integrity-disaster interface and (3) I had the pleasure of editing this article.

I’ve blogged about quite a few papers on ecosystem services (including some of my own) because I think making the link between ecosystem integrity and human health, wealth and well-being are some of the best ways to convince Joe Bloggs that saving species he’ll never probably see are in his and his family’s best (and selfish) interests. Convincing the poverty-stricken, the greedy and the downright stupid of biodiversity’s inherent value will never, ever work (at least, it hasn’t worked yet).

Today’s feature paper discusses an increasingly relevant policy conundrum in conservation – altering coastal ecosystems such that planted/restored/conserved vegetation minimises the negative impacts of extreme weather events (e.g., tsunamis, cyclones, typhoons and hurricanes): the so-called ‘bioshield’ effect. The idea is attractive – coastal vegetation acts to buffer human development and other land features from intense wave action, so maintain/restore it at all costs.

The problem is, as Feagin and colleagues point out in their poignant review, ‘bioshields’ don’t really seem to have much effect in attenuating the big waves resulting from the extreme events, the very reason they were planted in the first place. Don’t misunderstand them – keeping ecosystems like mangroves and other coastal communities intact has enormous benefits in terms of biodiversity conservation, minimised coastal erosion and human livelihoods. However, with massive coastal development in many parts of the world, the knee-jerk reaction has been to plant up coasts with any sort of tree/shrub going without heeding these species’ real effects. Indeed, many countries have active policies now to plant invasive species along coastal margins, which not only displace native species, they can displace humans and likely play little part in any wave attenuation.

This sleeping giant of a conservation issue needs some serious re-thinking, argue the authors, especially in light of predicted increases in extreme storm events resulting from climate change. I hope policy makers listen to that plea. I highly recommend the read.

![]() Feagin, R., Mukherjee, N., Shanker, K., Baird, A., Cinner, J., Kerr, A., Koedam, N., Sridhar, A., Arthur, R., Jayatissa, L., Lo Seen, D., Menon, M., Rodriguez, S., Shamsuddoha, M., & Dahdouh-Guebas, F. (2009). Shelter from the storm? Use and misuse of coastal vegetation bioshields for managing natural disasters Conservation Letters DOI: 10.1111/j.1755-263X.2009.00087.x

Feagin, R., Mukherjee, N., Shanker, K., Baird, A., Cinner, J., Kerr, A., Koedam, N., Sridhar, A., Arthur, R., Jayatissa, L., Lo Seen, D., Menon, M., Rodriguez, S., Shamsuddoha, M., & Dahdouh-Guebas, F. (2009). Shelter from the storm? Use and misuse of coastal vegetation bioshields for managing natural disasters Conservation Letters DOI: 10.1111/j.1755-263X.2009.00087.x

Couldn’t resist posting this – a gem for anyone who has ever had their paper go through the peer-review crunch.

Way back in 1989, Jared Diamond defined the ‘evil quartet’ of habitat destruction, over-exploitation, introduced species and extinction cascades as the principal drivers of modern extinctions. I think we could easily update this to the ‘evil quintet’ that includes climate change, and I would even go so far as to add extinction synergies as a the sixth member of the ‘evil sextet’.

Way back in 1989, Jared Diamond defined the ‘evil quartet’ of habitat destruction, over-exploitation, introduced species and extinction cascades as the principal drivers of modern extinctions. I think we could easily update this to the ‘evil quintet’ that includes climate change, and I would even go so far as to add extinction synergies as a the sixth member of the ‘evil sextet’.

But the future could hold quite a few more latent threats to biodiversity, and a corresponding number of potential solutions to its degradation. That’s why Bill Sutherland of Cambridge University recently got together with some other well-known scientists and technology leaders to do a ‘horizon scanning’ exercise to define what these threats and solutions might be in the immediate future. It’s an interesting, eclectic and somewhat enigmatic list, so I thought I’d summarise it here. The paper is entitled A horizon scan of global conservation issues for 2010 and was recently published online in Trends in Ecology and Evolution.

In no particular order or relative rank, Sutherland and colleagues list the following 15 ‘issues’ that I’ve broadly divided into ‘Emerging Threats’ and ‘Potential Solutions’:

Emerging Threats

Potential Solutions

Certainly some interesting ideas here and worth a thought or two. I wonder if the discipline of ‘conservation biology’ might even exist in 50-100 years – we might all end up being climate or agricultural engineers with a focus on biodiversity-friendly technology. Who knows?

![]() Sutherland, W., Clout, M., Côté, I., Daszak, P., Depledge, M., Fellman, L., Fleishman, E., Garthwaite, R., Gibbons, D., & De Lurio, J. (2009). A horizon scan of global conservation issues for 2010 Trends in Ecology & Evolution DOI: 10.1016/j.tree.2009.10.003

Sutherland, W., Clout, M., Côté, I., Daszak, P., Depledge, M., Fellman, L., Fleishman, E., Garthwaite, R., Gibbons, D., & De Lurio, J. (2009). A horizon scan of global conservation issues for 2010 Trends in Ecology & Evolution DOI: 10.1016/j.tree.2009.10.003