Bill Laurance asked me to reproduce his latest piece originally published at Yale University‘s Environment 360 website.

—

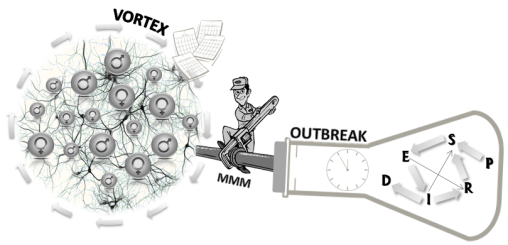

We live in an era of unprecedented road and highway expansion — an era in which many of the world’s last tropical wildernesses, from the Amazon to Borneo to the Congo Basin, have been penetrated by roads. This surge in road building is being driven not only by national plans for infrastructure expansion, but by industrial timber, oil, gas, and mineral projects in the tropics.

Few areas are unaffected. Brazil is currently building 7,500 km of new paved highways that crisscross the Amazon basin. Three major new highways are cutting across the towering Andes mountains, providing a direct link for timber and agricultural exports from the Amazon to resource-hungry Pacific Rim nations, such as China. And in the Congo basin, a recent satellite study found a burgeoning network of more than 50,000 km of new logging roads. These are but a small sample of the vast number of new tropical roads, which inevitably open up previously intact tropical forests to a host of extractive and economic activities.

“Roads,” said the eminent ecologist Thomas Lovejoy, “are the seeds of tropical forest destruction.”

Despite their environmental costs, the economic incentives to drive roads into tropical wilderness are strong. Governments view roads as a cost-effective means to promote economic development and access natural No other region can match the tropics for the sheer scale and pace of road expansion. resources. Local communities in remote areas often demand new roads to improve access to markets and medical services. And geopolitically, new roads can be used to help secure resource-rich frontier regions. India, for instance, is currently constructing and upgrading roads to tighten its hold on Arunachal Pradesh state, over which it and China formerly fought a war.