The last set of biodiversity cartoons for 2017. See full stock of previous ‘Cartoon guide to biodiversity loss’ compendia here.

—

Here’s another set of biodiversity cartoons to make you giggle, groan, and contemplate the Anthropocene extinction crisis. See full stock of previous ‘Cartoon guide to biodiversity loss’ compendia here.

—

One potentially useful metric to measure how different nations value their biodiversity is just how much of a country’s land its government sets aside to protect its natural heritage and resources. While this might not necessarily cover all the aspects of ‘environment’ we need to explore, we know from previous research that the more emphasis a country places on protecting its biodiversity, the more it actually achieves this goal. This might sound intuitive, but there is no shortage of what have become known as ‘paper parks’ around the world, which are essentially only protected in principle, but not in practice.

One potentially useful metric to measure how different nations value their biodiversity is just how much of a country’s land its government sets aside to protect its natural heritage and resources. While this might not necessarily cover all the aspects of ‘environment’ we need to explore, we know from previous research that the more emphasis a country places on protecting its biodiversity, the more it actually achieves this goal. This might sound intuitive, but there is no shortage of what have become known as ‘paper parks’ around the world, which are essentially only protected in principle, but not in practice.

For example, if a national park or some other type of protected area is not respected by the locals (who might rightly or wrongly perceive them as a limitation of their ‘rights’ of exploitation), or is pilfered by corrupt government officials in cahoots with extractive industries like logging or mining, then the park does not do well in protecting the species it was designed to safeguard. So, even though the proportion of area protected within a country is not a perfect reflection of its environmental performance, it tends to indicate to what extent its government, and therefore, its people, are committed to saving its natural heritage.

I’m travelling again, so here’s another set of fishy cartoons to appeal to your sense of morbid fascination with biodiversity loss in the sea. See full stock of previous ‘Cartoon guide to biodiversity loss’ compendia here.

—

Three of the coral species studied by Muir (2): (a) Acropora pichoni: Pohnpei Island, Pacific Ocean — deep-water species/IUCN ‘Near threatened’; (b) Acropora divaricate: Maldives, Indian ocean — mid-water species/IUCN ‘Near threatened’; and (c) Acropora gemmifera: Orpheus Island, Australia — shallow-water species/IUCN ‘Least Concern’. The IUCN states that the 3 species are vulnerable to climate change (acidification, temperature extremes) and demographic booms of the invading predator, the crown-of-thorns starfish Acanthaster planci. Photos courtesy of Paul Muir.

Global warming of the atmosphere and the oceans is modifying the distribution of many plants and animals. However, marine species are bound to face non-thermal barriers that might preclude their dispersal over wide stretches of the sea. Sunlight is one of those invisible obstacles for corals from the Indian and Pacific Oceans.

If we were offered a sumptuous job overseas, our professional success in an unknown place could be limited by factors like cultural or linguistic differences that have nothing to do with our work experience or expertise. If we translate this situation into biodiversity terms, one of the best-documented effects of global warming is the gradual dispersal of species tracking their native temperatures from the tropics to the poles (1). However, as dispersal progresses, many species encounter environmental barriers that are not physical (e.g., a high mountain or a wide river), and whose magnitude could be unrelated to ambient temperatures. Such invisible obstacles can prevent the establishment of pioneer populations away from the source.

Corals are ideal organisms to study this phenomenon because their life cycle is tightly geared to multiple environmental drivers (see ReefBase: Global Information System for Coral Reefs). Indeed, the growth of a coral’s exoskeleton relies on symbiotic zooxanthellae (see video and presentation), a kind of microscopic algae (Dinoflagellata) whose photosynthetic activity is regulated by sea temperature, photoperiod and dissolved calcium in the form of aragonite, among other factors.

My travel is finishing for now, but while in transit I’m obliged to do another instalment of biodiversity cartoons (and the second for 2017). See full stock of previous ‘Cartoon guide to biodiversity loss’ compendia here.

—

Number 41 of my semi-regular instalment of biodiversity cartoons, and the first for 2017. See full stock of previous ‘Cartoon guide to biodiversity loss’ compendia here.

—

Tired of living in a world where you’re constrained by inconvenient truths, irritating evidence and incommodious facts? 2016 must have been great for you. But in conservation, the fight against the ‘post-truth’ world is getting a little extra ammunition this year, as the Conservation Evidence project launches its updated book ‘What Works in Conservation 2017’.

Conservation Evidence, as many readers of this blog will know, is the brainchild of conservation heavyweight Professor Bill Sutherland, based at Cambridge University in the UK. Like all the best ideas, the Conservation Evidence project is at once staggeringly simple and breathtakingly ambitious — to list every conservation intervention ever cooked up around the world, and see how well, in the cold light of evidence, they actually worked. The project is ongoing, with new chapters of evidence added every year grouped by taxa, habitat or topic — all available for free on www.conservationevidence.com.

‘What Works in Conservation’ is a book that summarises the key findings from the Conservation Evidence website, and presents them in a simple, clear format, with links to where more information can be found on each topic. Experts (some of us still listen to them, Michael) review the evidence and score every intervention for its effectiveness, the certainty of the evidence and any harmful side effects, placing each intervention into a colour coded category from ‘beneficial’ to ‘likely to be ineffective or harmful.’ The last ‘What Works’ book included chapters on birds, bats, amphibians, soil fertility, natural pest control, some aspects of freshwater invasives and farmland conservation in Europe; new for 2017 is a chapter on forests and more species added to freshwater invasives. Read the rest of this entry »

Climate change caused by industrialisation is modifying the structure and function of the Biosphere. As we uncork 2017, our team launches a monthly section on plant and animal responses to modern climate change in the Spanish magazine Quercus – with an English version in Conservation Bytes. The initiative is the outreach component of a research project on the expression and evolution of heat-shock proteins at the thermal limits of Iberian lizards (papers in progress), supported by the British Ecological Society and the Spanish Ministry of Economy, Industry and Competitiveness. The series will feature key papers (linking climate change and biodiversity) that have been published in the primary literature throughout the last decade. To set the scene, we start off putting the emphasis on how people perceive climate change.

Salvador Herrando-Pérez, David R. Vieites & Miguel B. Araújo

—

“I would like to mention a cousin of mine, who is a Professor in Physics at the University of Seville – and asked about this matter [climate change], he stated: listen, I have gathered ten of the top scientists worldwide, and none has guaranteed what the weather will be like tomorrow in Seville, so how could anyone predict what is going to occur in the world 300 years ahead?”

Mariano Rajoy (Spanish President from 2011 to date) in a public speech on 22 October 2007

—

Weather (studied by meteorology) behaves like a chaotic system, so a little variation in the atmosphere can trigger large meteorological changes in the short term that are hard to predict. On the contrary, climate (studied by climatology) is a measure of average conditions in the long term and thus far more predictable than weather. There is less uncertainty in a climate prediction for the next century than in a weather prediction for the next month. The incorrect statement made by the Spanish President reflects harsh misinformation and/or lack of environment-related knowledge among our politicians.

Climate has changed consistently from the onset of the Industrial Revolution. The IPCC’s latest report stablishes with 95 to 100% certainty (solid evidence and high consensus given published research) that greenhouse gases from human activities are the main drivers of global warming since the second half of the 20th Century (1,2). The IPCC also flags that current concentrations of those gases have no parallel in the last 800,000 years, and that climate predictions for the 21st Century vary mostly according to how we manage our greenhouse emissions (1,3). Read the rest of this entry »

As I have done for the last three years (2015, 2014, 2013), here’s another retrospective list of the top 20 influential conservation papers of 2016 as assessed by experts in F1000 Prime.

As I have done for the last three years (2015, 2014, 2013), here’s another retrospective list of the top 20 influential conservation papers of 2016 as assessed by experts in F1000 Prime.

That’s ’40’, of course. Six more biodiversity cartoons, and the last for 2016. See full stock of previous ‘Cartoon guide to biodiversity loss’ compendia here.

—

As some know, I dabble a bit in the carbon affairs of the boreal zone, and so when writer Christine Ottery interviewed me about the topic, I felt compelled to reproduce her article here (originally published on EnergyDesk).

—

A view of the Waswanipi-Broadback forest in the Abitibi region of northern Quebec, one of the last remaining intact boreal forests in the Canadian province (source: EnergyDesk).

The boreal forest encircles the Earth around and just below the Arctic Circle like a big carbon-storing hug. It can mostly be found covering large swathes of Russia, Canada and Alaska, and some Scandinavian countries.

In fact, the boreal – sometimes called by its Russian name ‘taiga’ or ‘Great Northern Forest’ – is perhaps the biggest terrestrial carbon store in the world.

So it’s important to protect in a world where we’re aiming for 1.5 or – at worst – under two degrees celsius of global warming.

“Our capacity to limit average global warming to less than 2 degrees is already highly improbable, so every possible mechanism to reduce emissions must be employed as early as possible. Maintaining and recovering our forests is part of that solution,” Professor Corey Bradshaw, a leading researcher into boreal forests based at the University of Adelaide, told Energydesk.

It’s not that tropical rainforests aren’t important, but recent research led by Bradshaw published in Global and Planetary Change shows that that there is more carbon held in the boreal forests than previously realised.

But there’s a problem. Read the rest of this entry »

Like most local tragedies, it seems to take some time before the news really grabs the overseas audience by the proverbial goolies. That said, I’m gobsmacked that the education tragedy unfolding in South Africa since late 2015 is only now starting to be appreciated by the rest of the academic world.

Like most local tragedies, it seems to take some time before the news really grabs the overseas audience by the proverbial goolies. That said, I’m gobsmacked that the education tragedy unfolding in South Africa since late 2015 is only now starting to be appreciated by the rest of the academic world.

You might have seen the recent Nature post on the issue, and I do invite you to read that if all this comes as news to you. I suppose I had the ‘advantage’ of getting to know a little bit more about what is happening after talking to many South African academics in the Kruger in September. In a word, the situation is dire.

We’re probably witnessing a second Zimbabwe in action, with the near-complete meltdown of science capacity in South Africa as a now very real possibility. Whatever your take on the causes, justification, politics, racism, or other motivation underlying it all, the world’s conservation biologists should be very, very worried indeed.

Six more biodiversity cartoons coming to you all the way from Sweden (where I’ve been all week). See full stock of previous ‘Cartoon guide to biodiversity loss’ compendia here.

—

I admit that I might be stepping out on a bit of a dodgy limb by claiming ‘greatest’ in the title. That’s a big call, and possibly a rather subjective one at that. Regardless, I think it is one of the great conservation tragedies of the Anthropocene, and few people outside of a very specific discipline of conservation ecology seem to be talking about it.

I admit that I might be stepping out on a bit of a dodgy limb by claiming ‘greatest’ in the title. That’s a big call, and possibly a rather subjective one at that. Regardless, I think it is one of the great conservation tragedies of the Anthropocene, and few people outside of a very specific discipline of conservation ecology seem to be talking about it.

I’m referring to freshwater biodiversity.

I’m no freshwater biodiversity specialist, but I have dabbled from time to time, and my recent readings all suggest that a major crisis is unfolding just beneath our noses. Unfortunately, most people don’t seem to give a rat’s shit about it.

Sure, we can get people riled by rhino and elephant poaching, trophy hunting, coral reefs dying and tropical deforestation, but few really seem to appreciate that the stakes are arguably higher in most freshwater systems. Read the rest of this entry »

I’ve been a bit mad preparing for an upcoming conference, so I haven’t had a lot of time lately to blog about interesting developments in the conservation world. However, it struck me today that my preparations provide ideal material for a post about the future of Africa’s biodiversity.

I’ve been lucky enough to be invited to the University of Pretoria Mammal Research Unit‘s 50th Anniversary Celebration conference to be held from 12-16 September this year in Kruger National Park. Not only will this be my first time to Africa (I know — it has taken me far too long), the conference will itself be in one of the world’s best-known protected areas.

While decidedly fortunate to be invited, I am a bit intimidated by the line-up of big brains that will be attending, and of the fact that I know next to bugger all about African mammals (in a conservation science sense, of course). Still, apparently my insight as an outsider and ‘global’ thinker might be useful, so I’ve been hard at it the last few weeks planning my talk and doing some rather interesting analyses. I want to share some of these with you now beforehand, although I won’t likely give away the big prize until after I return to Australia.

I’ve been asked to talk about human population pressures on (southern) African mammal species, which might seem simple enough until you start to delve into the complexities of just how human populations affect wildlife. It’s simply from the perspective that human changes to the environment (e.g., deforestation, agricultural expansion, hunting, climate change, etc.) do cause species to dwindle and become extinct faster than they otherwise would (hence the entire field of conservation science). However, it’s another thing entirely to attempt to predict what might happen decades or centuries down the track. Read the rest of this entry »

Another six biodiversity cartoons for your midday chuckle & groan. There’s even one in there that takes the mickey out of some of my own research (see if you can figure out which one). See full stock of previous ‘Cartoon guide to biodiversity loss’ compendia here.

—

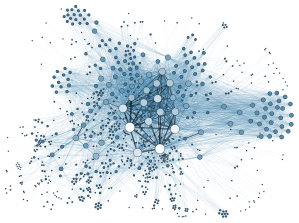

I’ve just read an interesting new study that was sent to me by the lead author, Giovanni Strona. Published the other day in Nature Communications, Strona & Lafferty’s article entitled Environmental change makes robust ecological networks fragile describes how ecological communities (≈ networks) become more susceptible to rapid environmental changes depending on how long they’ve had to evolve and develop under stable conditions.

I’ve just read an interesting new study that was sent to me by the lead author, Giovanni Strona. Published the other day in Nature Communications, Strona & Lafferty’s article entitled Environmental change makes robust ecological networks fragile describes how ecological communities (≈ networks) become more susceptible to rapid environmental changes depending on how long they’ve had to evolve and develop under stable conditions.

Using the Avida Digital Evolution Platform (a free, open-source scientific software platform for doing virtual experiments with self-replicating and evolving computer programs), they programmed evolving host-parasite pairs in a virtual community to examine how co-extinction rate (i.e., extinctions arising in dependent species — in this case, parasites living off of hosts) varied as a function of the complexity of the interactions between species.

Starting from a single ancestor digital organism, the authors let evolve several artificial life communities for hundred thousands generation under different, stable environmental settings. Such communities included both free-living digital organisms and ‘parasite’ programs capable of stealing their hosts’ memory. Throughout generations, both hosts and parasites diversified, and their interactions became more complex. Read the rest of this entry »

I’ve just returned from a short trip to the National Centre for Biological Sciences (NCBS) in Bangalore, Karnataka, one of India’s elite biological research institutes.

Panorama of a forested landscape (Savandurga monolith in the background) just south of Bangalore, Karnataka (photo: CJA Bradshaw)

I was invited to give a series of seminars (you can see the titles here), and hopefully establish some new collaborations. My wonderful hosts, Deepa Agashe & Jayashree Ratnam, made sure I was busy meeting nearly everyone I could in ecology and evolution, and I’m happy to say that collaborations have begun. I also think NCBS will be a wonderful conduit for future students coming to Australia.

It was my first time visiting India1, and I admit that I had many preconceptions about the country that were probably unfounded. Don’t get me wrong — many of them were spot on, such as the glorious food (I particularly liked the southern India cuisine of dhosa, iddly & the various fruit-flavoured semolina concoctions), the insanity of urban traffic, the juxtaposition of extreme wealth and extreme poverty, and the politeness of Indian society (Indians have to be some of the politest people on the planet).

But where I probably was most at fault of making incorrect assumptions was regarding the state of India’s natural ecosystems, and in particular its native forests and grasslands. Read the rest of this entry »