As have many other scientists, I’ve whinged before about the exploitative nature of scientific publishing. What other industry obtains its primary material for free (submitted articles), has its construction and quality control done for free (reviewing & editing), and then sells its final products for immense profit back to the very people who started the process? It’s a fantastic recipe for making oodles of cash; had I been financially cleverer and more ethically bereft in my youth, I would have bought shares in publicly listed publishing companies.

As have many other scientists, I’ve whinged before about the exploitative nature of scientific publishing. What other industry obtains its primary material for free (submitted articles), has its construction and quality control done for free (reviewing & editing), and then sells its final products for immense profit back to the very people who started the process? It’s a fantastic recipe for making oodles of cash; had I been financially cleverer and more ethically bereft in my youth, I would have bought shares in publicly listed publishing companies.

How much time do we spend reviewing and editing each other’s manuscripts? Some have tried to work out these figures and prescribe ideal writing-to-reviewing/editing ratios, but it suffices to say that we spend a mind-bending amount of our time doing these tasks. While we might never reap the financial rewards of reviewing, we can now at least get some nominal credit for the effort.

While it has been around for nearly five years now, the company Publons1 has only recently come to my attention. At first I wondered about the company’s modus operandi, but after discovering that academics can use their services completely free of charge, and that the company funds itself by “… partnering with publishers” (at least someone is getting something out of them), I believe it’s as about as legitimate and above-board as it gets.

So what does Publons do? They basically list the journals for which you have reviewed and/or edited. Whoah! (I can almost hear you say). How do I protect my anonymity? Read the rest of this entry »

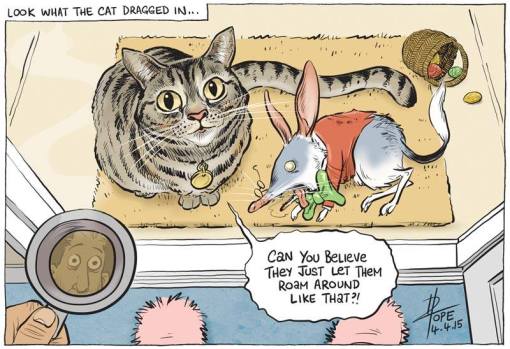

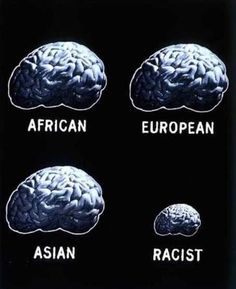

With all the nasty nationalism and xenophobia gurgling nauseatingly to the surface of our political discourse1 these days, it is probably worth some reflection regarding the role of multiculturalism in science. I’m therefore going to take a stab, despite being in most respects a ‘golden child’ in terms of privilege and opportunity (I am, after all, a middle-aged Caucasian male living in a wealthy country). My cards are on the table.

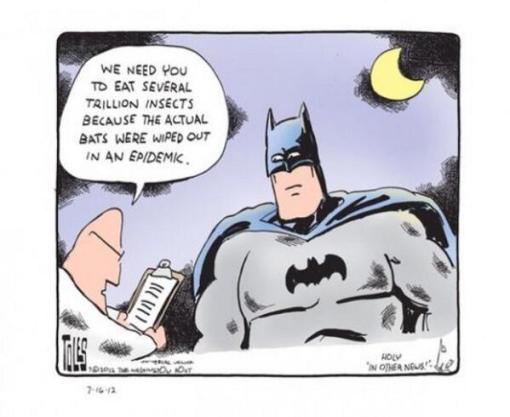

With all the nasty nationalism and xenophobia gurgling nauseatingly to the surface of our political discourse1 these days, it is probably worth some reflection regarding the role of multiculturalism in science. I’m therefore going to take a stab, despite being in most respects a ‘golden child’ in terms of privilege and opportunity (I am, after all, a middle-aged Caucasian male living in a wealthy country). My cards are on the table. We scientists can unfortunately be real bastards to each other, and no other interaction brings out that tendency more than peer review. Of course no one, no matter how experienced, likes to have a manuscript rejected. People hate to be on the receiving end of any criticism, and scientists are certainly no different. Many reviews can be harsh and unfair; many reviewers ‘miss the point’ or are just plain nasty.

We scientists can unfortunately be real bastards to each other, and no other interaction brings out that tendency more than peer review. Of course no one, no matter how experienced, likes to have a manuscript rejected. People hate to be on the receiving end of any criticism, and scientists are certainly no different. Many reviews can be harsh and unfair; many reviewers ‘miss the point’ or are just plain nasty.