Another corker from Salvador Herrando-Pérez:

Another corker from Salvador Herrando-Pérez:

—

Cinema fans know that choosing a movie by the newspaper’s commentary or the promotional poster might be a lottery. In the movie of nature, to confuse ‘the attractive’ with ‘the appropriate’ can compromise the life of an individual and its offspring, even to the extent of anticipating the extinction of an entire population or species.

Animals make daily choices about when, where or with whom to engage in basic activities like eating, hibernating, mating, migrating or resting. Those choices are often strongly tied to highly specific cues – e.g., air temperature, tree density, location of water, or smell of other individuals. And it happens to hair lice jumping from head to head among school kids, or to caribou forming their winter herds prior to the seasonal migration. All species, without exception, persist in nature because those ‘choices’ translate into survival or successful reproduction more often than do not. They are a kind of evolutionary memory imprinted in an organism’s genes and behaviour. However, sometimes the right choice (‘right’ meaning perceiving a cue for the role it actually has in the life cycle) places an individual in the worst of all possible situations. The environment cheats, ‘the attractive’ merely mimics ‘the appropriate’, and the individual fails to reproduce, starves, sickens, or even dies.

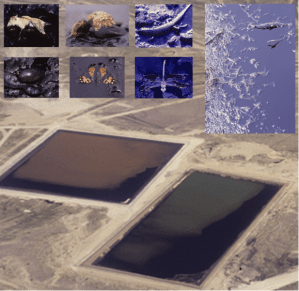

Figure 1. Water reservoirs tainted with fuel (see dark contours) in Kuwait following the Gulf War in the early 1990s. Overlaid pictures show the silhouettes of trapped odonates (right), vertebrates (top left) and invertebrates (bottom left) (Photos courtesy of Jochen Zeil).

At the mercy of mirages

During the Gulf War, the destruction of infrastructure for crude exploitation spilled large amounts of fuel in many water reservoirs over the desert landscape of Kuwait. A little later, Horváth and Zeil1 found agglomerations of dead insects (and a range of vertebrates) along the shores of these polluted reservoirs, and observed dragonflies drowning in their kamikaze attempt to spawn on the oily surface (Figure 1). This work stimulated further research whereby Horváth and his team in Budapest showed that odonates are attracted by light polarization at the surface of oiled water2 – hence ‘polarized light pollution’3. Not only that, they recorded insects struggling to spawn on or mate with riveting surfaces such as solar panels, asphalted roads, plastic bags or (creepy enough!) cemetery crypts4. It goes without saying: these insects are victims of a mirage.

Those habitats or features of the habitat that mislead an animal’s choice, often hampering the completion of its life cycle, are known as ‘ecological traps’ – in other words, the environmental cue is decoupled from the quality of the habitat it is meant to signal. Ecological traps were first described in the 1970s by Dwernychuk and Boag5. They found that ducks on the islands of Miquelon lake located their nests among those of seagulls despite the latter happily devoured their ducklings and eggs. When these islands emerged in the middle of last century, they were first colonized by common terns (Sterna hirundo). By defending their own nests ferociously from predators (mainly crows and magpies), the terns inadvertently shielded the nests of their ducky comrades. The Canadians hypothesized that when seagulls subsequently replace terns, the ducks continued to sense their new neighbours as a (now misleading) sign of protection. Read the rest of this entry »

I love these sorts of experiments. Ecology (and considering conservation ecology a special subset of the larger discipline) is a messy business, mainly because ecosystems are complex, non-linear, emergent, interactive, stochastic and meta-stable entities that are just plain difficult to manipulate experimentally. Therefore, making inference of complex ecological processes tends to be enhanced when the simplest components are isolated.

I love these sorts of experiments. Ecology (and considering conservation ecology a special subset of the larger discipline) is a messy business, mainly because ecosystems are complex, non-linear, emergent, interactive, stochastic and meta-stable entities that are just plain difficult to manipulate experimentally. Therefore, making inference of complex ecological processes tends to be enhanced when the simplest components are isolated.

I just returned from a week-long scientific mission in China sponsored by the

I just returned from a week-long scientific mission in China sponsored by the