Here’s a depressing emergency post by Fabiola Monty.

Here’s a depressing emergency post by Fabiola Monty.

—

I started working on this article to discuss how useful science is being ignored in Mauritius.

The Mauritian government has decided to implement a fruit bat cull as an ‘urgent response’ to the claims of huge economic losses by fruit farmers, a decision not supported by scientific evidence. We have now received confirmation in Mauritius through a local press communiqué that on 7 November 2015, The Mauritian Ministry of Agro Industry and Food Security in collaboration with the local Police Department and Special Mobile Force will start the culling of 18,000 bats in their natural habitats “with a view to reducing the extent of damages caused to fruits by bats”.

Tackling human-wildlife conflicts can indeed be challenging, but can the culling of 18,000 endemic Mauritian flying fox (Pteropus niger) resolve ‘human-wildlife conflict’ in the land of the dodo? In the case of Mauritius, scientific evidence not only demonstrates that the situation has been exaggerated, but that there are alternatives to bat culling that have been completely brushed aside by policy makers.

Are the Mauritius fruit bats agricultural pests?

Are the Mauritius fruit bats agricultural pests?

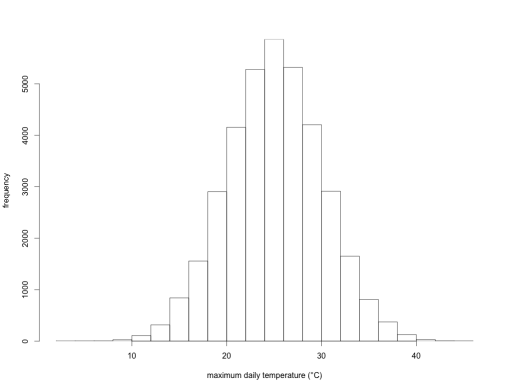

While fruit bats are being labelled as serious pests, scientific evidence shows instead that their impacts have been exaggerated. A recent (2014) study indicates that bats damage only 3-11% of fruit production, with birds also contributing to 1-8% of fruit loss. Rats are also probable contributors to fruit damage, but the extent remains unquantified. Interestingly, more fruits are lost (13-20%) because they are not collected in time and are left to over-ripen.

While the results of the study were communicated to legislators a few months before they made the decision to cull, it is clear that these were ignored in favour of preconceived assumptions.

Are there too many fruit bats? Read the rest of this entry »