That’s ’40’, of course. Six more biodiversity cartoons, and the last for 2016. See full stock of previous ‘Cartoon guide to biodiversity loss’ compendia here.

—

That’s ’40’, of course. Six more biodiversity cartoons, and the last for 2016. See full stock of previous ‘Cartoon guide to biodiversity loss’ compendia here.

—

Six more biodiversity cartoons coming to you all the way from Sweden (where I’ve been all week). See full stock of previous ‘Cartoon guide to biodiversity loss’ compendia here.

—

I admit that I might be stepping out on a bit of a dodgy limb by claiming ‘greatest’ in the title. That’s a big call, and possibly a rather subjective one at that. Regardless, I think it is one of the great conservation tragedies of the Anthropocene, and few people outside of a very specific discipline of conservation ecology seem to be talking about it.

I admit that I might be stepping out on a bit of a dodgy limb by claiming ‘greatest’ in the title. That’s a big call, and possibly a rather subjective one at that. Regardless, I think it is one of the great conservation tragedies of the Anthropocene, and few people outside of a very specific discipline of conservation ecology seem to be talking about it.

I’m referring to freshwater biodiversity.

I’m no freshwater biodiversity specialist, but I have dabbled from time to time, and my recent readings all suggest that a major crisis is unfolding just beneath our noses. Unfortunately, most people don’t seem to give a rat’s shit about it.

Sure, we can get people riled by rhino and elephant poaching, trophy hunting, coral reefs dying and tropical deforestation, but few really seem to appreciate that the stakes are arguably higher in most freshwater systems. Read the rest of this entry »

I’ve just returned from a life-changing trip to South Africa, not just because it was my first time to the continent, but also because it has redefined my perspective on the megafauna extinctions of the late Quaternary. I was there primarily to attend the University of Pretoria’s Mammal Research Institute 50thAnniversary Celebration conference.

As I reported in my last post, the poaching rates in one of the larger, best-funded national parks in southern Africa (the Kruger) are inconceivably high, such that for at least the two species of rhino there (black and white), their future persistence probability is dwindling with each passing week. African elephants are probably not far behind.

As one who has studied the megafauna extinctions in the Holarctic, Australia and South America over the last 50,000 years, the trip to Kruger was like stepping back into the Pleistocene. I’ve always dreamed of walking up to a grazing herd of mammoths, woolly rhinos or Diprotodon, but of course, that’s impossible. What is entirely possible though is driving up to a herd of 6-tonne elephants and watching them behave naturally. In the Kruger anyway, you become almost blasé about seeing yet another group of these impressive beasts as you try to get that rare glimpse of a leopard, wild dogs or sable antelope (missed the two former, but saw the latter). Read the rest of this entry »

Another six biodiversity cartoons for your midday chuckle & groan. There’s even one in there that takes the mickey out of some of my own research (see if you can figure out which one). See full stock of previous ‘Cartoon guide to biodiversity loss’ compendia here.

—

source: http://goo.gl/do6Q85

As many of you know, I have held the ‘Sir Hubert Wilkins Chair of Climate Change’ at the University of Adelaide since January 2015. My colleague and friend, Barry Brook, was the foundation Chair-holder from 2006-2014.

Initially set up by Government of South Australia to “… advise government, industry, and the community on how to tackle climate change …”, it now is only a titular position based at the University. While I certainly try to live up to the aims of the Chair, it’s even more difficult to live up to the namesake himself — Sir George Hubert Wilkins.

Given I’ve held the position now for over a year and half, I’ve had plenty of time to read about this legendary South Australian (I do choose my words carefully here). Despite most Australians having never heard of the man, it is my opinion that he should be as well known in this country as other whitefella explorers such as Douglas Mawson, Matthew Flinders, Robert Burke, William Wills, and Charles Sturt.

Sadly, he is not well-known, for a litany of possible reasons ranging from spending so much time out of Australia, never having a formal qualification in many of the skills in which he excelled (e.g., geography, meteorology, aviation, engineering, cinematography, biology, etc.), disrespect from other contemporary Australian explorers, and some rather bizarre behaviour later in his career. The list of this man’s achievements is staggering, as was his ability to thumb his nose at death (who, I might add, tried her hardest to escort him off this mortal coil many times well before a heart attack claimed him at the age of 70).

Many books have been written about Wilkins, but as I slowly make my way through some of the better-written tomes, one unsung aspect of his career has struck a deep chord within me — it turns out that Wilkins was also a extremely concerned biodiversity conservationist. Read the rest of this entry »

Here’s a paper we’ve just had published in Science Advances (Synergistic roles of climate warming and human occupation in Patagonian megafaunal extinctions during the Last Deglaciation). It’s an excellent demonstration of our concept of extinction synergies that we published back in 2008.

Here’s a paper we’ve just had published in Science Advances (Synergistic roles of climate warming and human occupation in Patagonian megafaunal extinctions during the Last Deglaciation). It’s an excellent demonstration of our concept of extinction synergies that we published back in 2008.

—

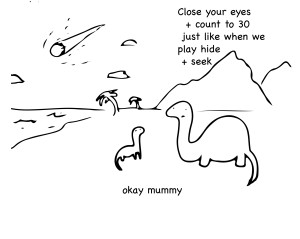

Giant Ice Age species including elephant-sized sloths and powerful sabre-toothed cats that once roamed the windswept plains of Patagonia, southern South America, were finally felled by a perfect storm of a rapidly warming climate and humans, a new study has shown.

Research published on Saturday in Science Advances, has revealed that it was only when the climate warmed, long after humans first arrived in Patagonia, did the megafauna suddenly die off around 12,300 years ago.

The timing and cause of rapid extinctions of the megafauna has remained a mystery for centuries.

“Patagonia turns out to be the Rosetta Stone – it shows that human colonisation didn’t immediately result in extinctions, but only as long as it stayed cold”. “Instead, more than 1000 years of human occupation passed before a rapid warming event occurred, and then the megafauna were extinct within a hundred years.”

The researchers, including from the University of Colorado Boulder, University of New South Wales and University of Magallanes in Patagonia, studied ancient DNA extracted from radiocarbon-dated bones and teeth found in caves across Patagonia, and Tierra del Fuego, to trace the genetic history of the populations. Species such as the South American horse, giant jaguar and sabre-toothed cat, and the enormous one-tonne short-faced bear (the largest land-based mammalian carnivore) were found widely across Patagonia, but seemed to disappear shortly after humans arrived. Read the rest of this entry »

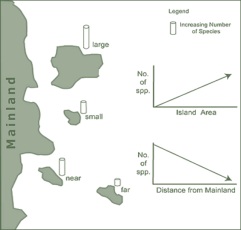

I’ve just read an elegant little study that has identified the main determinants of differences in the slope of species-area curves and species-accumulation curves.

I’ve just read an elegant little study that has identified the main determinants of differences in the slope of species-area curves and species-accumulation curves.

That’s a bit of a mouthful for the uninitiated, so if you don’t know much about species-area theory, let me give you a bit of background for why this is an important new discovery.

Perhaps one of the only ‘laws’ in ecology comes from the observation that as you sample from larger and larger areas of any habitat type, the number of species tends to increase. This of course originates from MacArthur & Wilson’s classic book, The Theory of Island Biography (1967), and while simple in basic concept, it has since developed into a multi-headed Hydra of methods, analysis, theory and jargon.

One of the most controversial aspects of generic species-area relationships is the effect of different sampling regimes, a problem I’ve blogged about before. Whether you are sampling once-contiguous forest of habitat patches in a ‘matrix’ of degraded landscape, a wetland complex, a coral reef, or an archipelago of true oceanic islands, the ‘ideal’ models and the interpretation thereof will likely differ, and in sometimes rather important ways from a predictive and/or applied perspective. Read the rest of this entry »

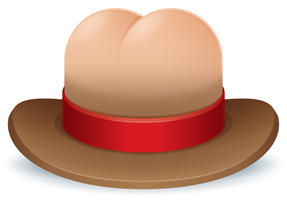

I’m starting a new series on ConservationBytes.com — one that exposes the worst environmental offenders on the planet.

I’m starting a new series on ConservationBytes.com — one that exposes the worst environmental offenders on the planet.

I’ve taken the idea from an independent media organisation based in Australia — Crikey — who has been running the Golden Arsehat of the Year awards since 2008. It’s a hilarious, but simultaneously maddening, way of shaming the worst kinds of people.

So in the spirit of a little good fun and environmental naming-and-shaming, I’d like to put together a good list of candidates for the inaugural Environmental Arsehat of the Year awards.

So I’m keen to receive your nominations, either privately via e-mail, the ConservationBytes.com message service, or even in the comments stream of this post. Once I receive a good list of candidates, I’ll do separate posts on particularly deserving individuals, followed by an online poll where you can vote for your (least) favourite Arsehat.

There are a few nomination rules, however. Read the rest of this entry »

While I’ve blogged about this before in general terms (here and here), I thought it wise to reproduce the (open-access) chapter of the same name published in late 2013 in the unfortunately rather obscure book The Curious Country produced by the Office of the Chief Scientist of Australia. I think it deserves a little more limelight.

While I’ve blogged about this before in general terms (here and here), I thought it wise to reproduce the (open-access) chapter of the same name published in late 2013 in the unfortunately rather obscure book The Curious Country produced by the Office of the Chief Scientist of Australia. I think it deserves a little more limelight.

—

As I stepped off the helicopter’s pontoon and into the swamp’s chest-deep, tepid and opaque water, I experienced for the first time what it must feel like to be some other life form’s dinner. As the helicopter flittered away, the last vestiges of that protective blanket of human technological innovation flew away with it.

Two other similarly susceptible, hairless, clawless and fangless Homo sapiens and I were now in the middle of one of the Northern Territory’s largest swamps at the height of the crocodile-nesting season. We were there to collect crocodile eggs for a local crocodile farm that, ironically, has assisted the amazing recovery of the species since its near-extinction in the 1960s. Removing the commercial incentive to hunt wild crocodiles by flooding the international market with scar-free, farmed skins gave the dwindling population a chance to recover.

Conservation scientists like me rejoice at these rare recoveries, while many of our fellow humans ponder why we want to encourage the proliferation of animals that can easily kill and eat us. The problem is, once people put a value on a species, it is usually consigned to one of two states. It either flourishes as do domestic crops, dogs, cats and livestock, or dwindles towards or to extinction. Consider bison, passenger pigeons, crocodiles and caviar sturgeon.

Conservation scientists like me rejoice at these rare recoveries, while many of our fellow humans ponder why we want to encourage the proliferation of animals that can easily kill and eat us. The problem is, once people put a value on a species, it is usually consigned to one of two states. It either flourishes as do domestic crops, dogs, cats and livestock, or dwindles towards or to extinction. Consider bison, passenger pigeons, crocodiles and caviar sturgeon.

As a conservation scientist, it’s my job not only to document these declines, but to find ways to prevent them. Through careful measurement and experiments, we provide evidence to support smart policy decisions on land and in the sea. We advise on the best way to protect species in reserves, inform hunters and fishers on how to avoid over-harvesting, and demonstrate the ways in which humans benefit from maintaining healthy ecosystems. Read the rest of this entry »

Last July I wrote about a Science paper of ours demonstrating that there was a climate-change signal in the overall extinction pattern of megafauna across the Northern Hemisphere between about 50,000 and 10,000 years ago. In that case, it didn’t have anything to do with ice ages (sorry, Blue Sky Studios); rather, it was abrupt warming periods that exacerbated the extinction pulse instigated by human hunting.

Last July I wrote about a Science paper of ours demonstrating that there was a climate-change signal in the overall extinction pattern of megafauna across the Northern Hemisphere between about 50,000 and 10,000 years ago. In that case, it didn’t have anything to do with ice ages (sorry, Blue Sky Studios); rather, it was abrupt warming periods that exacerbated the extinction pulse instigated by human hunting.

Contrary to some appallingly researched media reports, we never claimed that these extinctions arose only from warming, because the evidence is more than clear that humans were the dominant drivers across North America, Europe and northern Asia; we simply demonstrated that warming periods had a role to play too.

A cursory glance at the title of this post without appreciating the complexity of how extinctions happen might lead you to think that we’re all over the shop with the role of climate change. Nothing could be farther from the truth.

Instead, we report what the evidence actually says, instead of making up stories to suit our preconceptions.

So it is with great pleasure that I report our new paper just out in Nature Communications, led by my affable French postdoc, Dr Frédérik Saltré: Climate change not to blame for late Quaternary megafauna extinctions in Australia.

Of course, it was a huge collaborative effort by a crack team of ecologists, palaeontologists, geochronologists, paleo-climatologists, archaeologists and geneticists. Only by combining the efforts of this diverse and transdisciplinary team could we have hoped to achieve what we did. Read the rest of this entry »

My good friend and tropical conservation rockstar, Bill Laurance, just emailed me and asked if I could repost his recent The Conversation article here on ConservationBytes.com.

He said:

It’s going completely viral (26,000 reads so far) in just three days. It’s been republished in The Ecologist, I Fucking Love Science, and several other big media outlets.

Several non-scientists have said it really helped them to understand what’s known versus unknown in climate-change research—which was helpful because they feel pummelled by all the research and draconian stuff that gets reported and have problems parsing out what’s likely versus speculative.

With an introduction like that, you’ll just have to read it!

—

“It’s tough to make predictions, especially about the future”: so goes a Danish proverb attributed variously to baseball coach Yogi Berra and physicist Niels Bohr. Yet some things are so important — such as projecting the future impacts of climate change on the environment — that we obviously must try.

An Australian study published last week predicts that some rainforest plants could see their ranges reduced 95% by 2080. How can we make sense of that given the plethora of climate predictions?

In a 2002 press briefing, Donald Rumsfeld, President George W. Bush’s Secretary of Defence, distinguished among different kinds of uncertainty: things we know, things we know we don’t know, and things we don’t know we don’t know. Though derided at the time for playing word games, Rumsfeld was actually making a good point: it’s vital to be clear about what we’re unclear about.

So here’s my attempt to summarise what we think we know, don’t know, and things that could surprise us about climate change and the environment.

We know that carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere have risen markedly in the last two centuries, especially in recent decades, and the Earth is getting warmer. Furthermore, 2014 was the hottest year ever recorded. That’s consistent with what we’d expect from the greenhouse effect. Read the rest of this entry »

How do you prevent declines of species you cannot even see? This is (and has always been) the dilemma for fisheries because, well, humans don’t live underwater. Even when we strap on a metal tank full of air and a pair of fins, we’re still more or less like wounded astronauts peering through a narrow window of glass at the huge, largely empty, ocean space. It’s little wonder then that we have a fairly crap system of estimating fish abundance, and an even worse track record of managing them sustainably.

But humans love to eat fish – the total world estimate of legal fisheries landings is something in the vicinity of 190 million tonnes in 2013, up from 18 million tonnes in 1950 (according to FAO). We’re probably familiar with some of the losers of that massive harvest, with species like tunas, bill fishes and orange roughy making the news for catastrophic declines in abundance over the last 30-40 years. And we’re not even talking about the estimated tragedy that is illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing.

Back in 1999, the FAO started to report that sharks – the new-ish target of many world fisheries resulting from the commercial extinction of many other fin fish fisheries – we’re starting to take the hit. Once generally ignored by fishing industries, sharks soon became popular target species. Then in 2003, Julia Baum and colleagues famously (and somewhat controversially) sounded the alarm for sharks in the Gulf of Mexico by some claims of major and catastrophic declines of large, predatory sharks. While some of the subsequent to-ing and fro-ing in the literature challenged these claims, Baum’s excellent work was ultimately vindicated.

Since then, more and more evidence that sharks are in trouble has surfaced, including the assessment of the reported (again, only legal) catch indicated heavy depletion of coastal sharks even by 1975, and the estimate that 25% of all shark and ray species have an elevated extinction risk, mainly resulting from overfishing. Now even the direct fisheries landings statistics are confirming this grim tale. Read the rest of this entry »

Extinction is forever, right? Yes, it’s true that once the last individual of a species dies (apart from insane notions that de-extinction will do anything to resurrect a species in perpetuity), the species is extinct. However, the answer can also be ‘no’ when you are limited by poor sampling. In other words, when you think something went extinct when in reality you just missed it.

Extinction is forever, right? Yes, it’s true that once the last individual of a species dies (apart from insane notions that de-extinction will do anything to resurrect a species in perpetuity), the species is extinct. However, the answer can also be ‘no’ when you are limited by poor sampling. In other words, when you think something went extinct when in reality you just missed it.

Most of you are familiar with the concept of Lazarus1 species – when we’ve thought of something long extinct that suddenly gets re-discovered by a wandering naturalist or a wayward fisher. In paleontological (and modern conservation biological) terms, the problem is formally described as the ‘Signor-Lipps’ effect, named2 after two American palaeontologists, Phil Signor3 and Jere Lipps. It’s a fairly simple concept, but it’s unfortunately ignored in most palaeontological, and to a lesser extent, conservation studies.

The Signor-Lipps effect arises because the last (or first) evidence (fossil or sighting) of a species presence has a nearly zero chance of heralding its actual timing of extinction (or appearance). In paleontological terms, it’s easy to see why. Fossilisation is in fact a nearly impossible phenomenon – all the right conditions have to be in place for a once-living biological organism to be fossilised: it either has to be buried quickly, in a place where nothing can decompose it (usually, an anoxic environment), and then turned to rock by the process of mineral replacement. It then has to resist transformation by not undergoing metamorphosis (e.g., vulcanism, extensive crushing, etc.). For more recent specimens, preservation can occur without the mineralisation process itself (e.g., bones or flesh in an anoxic bog). Then the bloody things have to be found by a diligent geologist or palaeontologist! In other words, the chances that any one organism is preserved as a fossil after it dies are extremely small. In more modern terms, individuals can go undetected if they are extremely rare or remote, such that sighting records alone are usually insufficient to establish the true timing of extinction. The dodo is a great example of this problem. Remember too that all this works in reverse – the first fossil or observation is very much unlikely to be the first time that the species was there. Read the rest of this entry »

[10.06.2015 update: Because of all the people looking for cartoon porn, I’ve slightly altered the title of this post. Should have predicted that one]

Third batch of six biodiversity cartoons for 2015 (see full stock of previous ‘Cartoon guide to biodiversity loss’ compendia here).

—

Second batch of six biodiversity cartoons for 2015 (see full stock of previous ‘Cartoon guide to biodiversity loss’ compendia here).

—