I’ve had the good fortune of being involved now in a several endeavours funded by the Australian Centre for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis (ACEAS); two of those were workshops targeting specific questions regarding estimating modern extinction rates and examining the effects of genetic bottlenecks on Australian biota. The third was a bit different, to say the least – it was a little along the lines of ‘build it, and they will come‘. In other words, what happens when you bung 40 loosely associated researchers in a room for two days? Does anything of substance result, or does it degenerate into a mere talk-fest. I’m happy to say the former. The details of the ACEAS ‘Grand Workshop‘ are now being finalised in a paper that should be submitted by the end of the month. The ACEAS report is reproduced below.

I’ve had the good fortune of being involved now in a several endeavours funded by the Australian Centre for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis (ACEAS); two of those were workshops targeting specific questions regarding estimating modern extinction rates and examining the effects of genetic bottlenecks on Australian biota. The third was a bit different, to say the least – it was a little along the lines of ‘build it, and they will come‘. In other words, what happens when you bung 40 loosely associated researchers in a room for two days? Does anything of substance result, or does it degenerate into a mere talk-fest. I’m happy to say the former. The details of the ACEAS ‘Grand Workshop‘ are now being finalised in a paper that should be submitted by the end of the month. The ACEAS report is reproduced below.

—

The Grand ACEAS Workshop was something of an experiment: what will happen when we bring 30 of Australia’s top scientists working on land management issues into the same room?

The Grand Workshop participants came from academia, research institutions and the government, and had all received ACEAS funding for working groups. David Keith, Ted Lefroy, Jasmyn Lynch, Wayne Meyer and Dick Williams were amongst the attendees of the two-day workshop.

And when this group of people came together wanting to analyse and synthesise ecological data, great things happened.

“We decided to focus on how carbon pricing legislation will affect land use change and how will that spill over into biodiversity persistence”, said Professor Corey Bradshaw, Director of Ecological Modelling at The University of Adelaide, who led the synthesis activity at the Grand ACEAS Workshop.

“Will carbon pricing lead to good outcomes for biodiversity, or negative ones, or will it have no bearing whatsoever?”

The workshop participants broke into five groups to discuss how the carbon tax legislation will change land use when it is introduced in July 2012, and the potential impact on biodiversity.

Some of the questions asked included:

- Is it enough simply to allow plants to re-grow to be eligible for carbon credits?

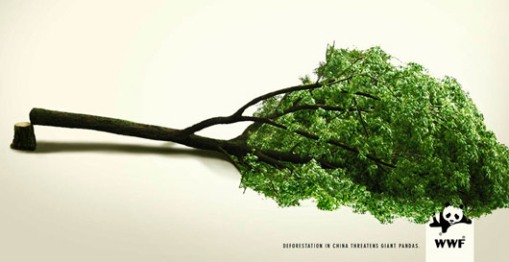

- How will an increase in forestry plantations impact biodiversity, water catchments and fire regimes?

- Will there be more kangaroo grazing to reduce methane emissions and erosion, replacing hard-hoofed livestock?

- Can you receive carbon credits for shooting large feral animals like goats, camels, deer and boars?

The groups found many opportunities for positive biodiversity outcomes with the carbon sequestration activities encouraged by carbon pricing, but there are also many potential ‘bio-perversities’. Read the rest of this entry »