Uncertainty is to science what the score is to music. Everything scientists measure is subject to various types of ‘error’ — from measurements to models. And climate change is no exception. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) is the United Nation’s scientific body informing the political response to the human disruption of our planet’s climate. In a recent paper, we reveal that the IPCC’s language to address climatic uncertainty is overly conservative in its assessment reports.

—

Uncertainty dominates our lives. We might grumble, but we generally accept the bus arriving late, the risotto being a little colder than we might want, or a blood test unexpectedly announcing higher cholesterol than usual. We even treat uncertainty as an inevitable outcome of many professions: meteorologists might fail to predict rain for our camping weekend, an investor might make back the money today that was lost yesterday, or Messi might fail to score in the last minute of a Champions League final.

So, we shouldn’t be surprised that scientific research is suffused with uncertainty. In fact, scientists indulge themselves with uncertainty. For them, acknowledging an uncertain outcome is not enough; instead, a critical component of their work is to quantify the amount of that uncertainty by, say, measuring the degree of variance (uncertainty) in the average height of a tree in a forest, or in the exact number of bees in a hive.

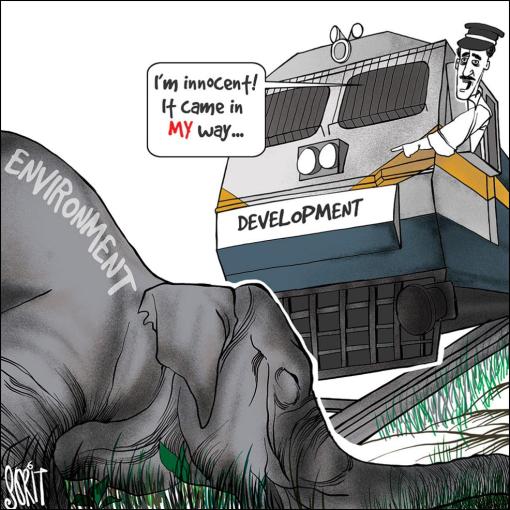

The treatment of uncertainty even gains added value when we deal with themes that directly affect our society — like climate change. But whoever communicates the uncertainty of climate science faces two formidable challenges. First, people often have a flawed understanding of science as a source of statements of fact. Instead, science is, in essence, about asking questions (1) and gradually refining the accuracy of our answers to those questions. Second, people perceive climate change through the lens of their ideology, education, and personal interests (2, 3, 4).

Therefore, what scientists say about the climate is not necessarily what some people will hear, even to the point that what scientists collectively recommend as ‘useful’ for addressing climate change might instead be deemed ‘useless’ by policymakers (5).

Mathematical jargon

The IPCC evaluates the technical literature about climate change, and publishes such comprehensive evaluations in the form of periodical ‘assessment reports’ (AR). Those reports — which receive vast, global attention — provide policy-relevant, but not policy-prescriptive, advice to national governments and international organizations. The reports also catch the eye of a variety of audiences such as business people, educators, scientists, and the public as a whole.

To date, the IPCC has published five assessment reports in 1990 (AR1), 1995 (AR2), 2001 (AR3), 2007 (A4) and 2014 (AR5), and the next one (see progress updates here) is scheduled for 2022 (AR6) (6). With a focus on climate change, each report comprises three components: (i) the physical basis of climate, (ii) its socio-economic consequences, and (iii) adaptation and mitigation options. Every component is elaborated by a different ‘working group’ in charge of editing, integrating, and synthesizing the inputs of multiple experts. Read the rest of this entry »

We are most fortunate that Dr

We are most fortunate that Dr

(reproduced from

(reproduced from

It has taken me a long time to decide to do this, but with role models like

It has taken me a long time to decide to do this, but with role models like

So, we go through the motions; we

So, we go through the motions; we

Just under two weeks ago,

Just under two weeks ago,