I’m winding down here for the year (although there might be a few more posts before the New Year), so here’s the latest batch of 6 biodiversity cartoons (see full stock of previous ‘Cartoon guide to biodiversity loss’ compendia here).

—

I’m winding down here for the year (although there might be a few more posts before the New Year), so here’s the latest batch of 6 biodiversity cartoons (see full stock of previous ‘Cartoon guide to biodiversity loss’ compendia here).

—

The saying “it isn’t rocket science” is a common cliché in English to state, rather sarcastically, that something isn’t that difficult (with the implication that the person complaining about it, well, shouldn’t). But I really think we should change the saying to “it isn’t ecology”, for ecology is perhaps one of the most complex disciplines in science (whereas rocket science is just ‘complicated’). One of our main goals is to predict how ecosystems will respond to change, yet what we’re trying to simplify when predicting is the interactions of millions of species and individuals, all responding to each other and to their outside environment. It becomes quickly evident that we’re dealing with a system of chaos. Rocket science is following recipes in comparison.

Because of this complexity, ecology is a discipline plagued by a lack of generalities. Few, if any, ecological laws exist. However, we do have an abundance of rules of thumb that mostly apply in most systems. I’ve written about a few of them here on ConservationBytes.com, such as the effect of habitat patch size on species diversity, the importance of predators for maintaining ecosystem stability, and that low genetic diversity doesn’t exactly help your chances of persisting. Another big one is, of course, that in an era of rapid change, big things tend to (but not always – there’s that lovely complexity again) drop off the perch before smaller things do.

The prevailing wisdom is that big species have slower life history rates (reproduction, age at first breeding, growth, etc.), and so cannot replace themselves fast enough when the pace of their environment’s change is too high. Small, rapidly reproducing species, on the other hand, can compensate for higher mortality rates and hold on (better) through the disturbance. Read the rest of this entry »

A few weeks ago I heard from an early-career researcher in the U.S. who had some intelligent things to say about getting jobs in conservation science based on a recent Conservation Biology paper she co-wrote. Of course, for all the PhDs universities are pumping out into the workforce, there will never be enough positions in academia for them all. Thus, many find their way into non-academic positions. But – does a PhD in science prepare you well enough for the non-academic world? Apparently not.

—

Many post-graduate students don’t start looking at job advertisements until we are actually ready to apply for a job. How often do we gleam the list of required skills and say, “If only I had done something to acquire project management skills or fundraising skills, then I could apply for this position…”? Many of us start post-graduate degrees assuming that our disciplinary training for that higher degree will prepare us appropriately for the job market. In conservation science, however, many non-disciplinary skills (i.e., beyond those needed to be a good scientist) are required to compete successfully for non-academic positions. What are these skills?

Our recent paper in Conservation Biology (Graduate student’s guide to necessary skills for nonacademic conservation careers) sifted through U.S. job advertisements and quantified how often different skills are required across three job sectors: nonprofit, government and private. Our analysis revealed that several non-disciplinary skills are particularly critical for job applicants in conservation science. The top five non-disciplinary skills were project management, interpersonal, written communication, program leadership and networking. Approximately 75% of the average job advertisement focused on disciplinary training and these five skills. In addition, the importance of certain skills differed across the different job sectors.

Below, we outline the paper’s major findings with regard to the top five skills, differences among sectors, and advice for how to achieve appropriate training while still in university. Read the rest of this entry »

|

| Unique in its genus, the saiga antelope inhabits the steppes and semi-desert environments in two sub-species split between Kazakhstan (Saiga tatarica tatarica, ~ 80% of the individuals) and Mongolia (Saiga tatarica mongolica). Locals hunt them for their meat and the (attributed) medicinal properties of male horns. Like many ungulates, the population is sensitive to winter severity and summer drought (which signal seasonal migrations of herds up to 1000 individuals). But illegal poaching has reduced the species from > 1 million in the 1970s to ~ 50000 currently (see RT video). The species has gone extinct in China and Ukraine, and has been IUCN “Critically Endangered” from 2002. The photo shows a male in The Centre for Wild Animals, Kalmykia, Russia (courtesy of Pavel Sorokin). |

In a planet approaching 7 billion people, individual identity for most of us goes largely unnoticed by the rest. However, individuals are important because each can promote changes at different scales of social organisation, from families through to associations, suburbs and countries. This is not only true for the human species, but for any species (1).

It is less than two decades since many ecologists started pondering the ways of applying the understanding of how individuals behave to the conservation of species (2-9), which some now refer to as ‘conservation behaviour’ (10, 11). The nexus seems straightforward. The decisions a bear or a shrimp make daily to feed, mate, move or shelter (i.e., their behaviour) affect their fitness (survival + fertility). Therefore, the sum of those decisions across all individuals in a population or species matters to the core themes handled by conservation biology for ensuring long-term population viability (12), i.e., counteracting anthropogenic impacts, and (with the distinction introduced by Cawley, 13) reversing population decline and avoiding population extinction.

To use behaviour in conservation implies that we can modify the behaviour of individuals to their own benefit (and mostly, to the species’ benefit) or define behavioural metrics that can be used as indicators of population threats. A main research area dealing with behavioural modification is that of anti-predator training of captive individuals prior to re-introduction. Laden with nuances, those training programs have yielded contrasting results across species, and have only tested a few instances of ‘success’ after release into the wild (14). For example, captive black-tailed prairie dogs (Cynomys ludovicianus) exposed to stuffed hawks, caged ferrets and rattlesnakes had higher post-release survival than untrained individuals in the grasslands of the North American Great Plains (15). A clear example of a threat metric is aberrant behaviour triggered by hunting. Eleanor Milner-Gulland et al. (16) have reported a 46 % reduction in fertility rates in the saiga antelope (Saiga tatarica) in Russia from 1993-2002. This species forms harems consisting of one alpha male and 12 to 30 females. Local communities have long hunted this species, but illegal poaching for horned males from the early 1990s (17) ultimately led to harems with a female surplus (with an average sex ratio up to 100 females per male!). In them, only a few dominant females seem to reproduce because they engage in aggressive displays that dissuade other females from accessing the males. Read the rest of this entry »

Laurance & Pimm organise another excellent tropical conservation open-letter initiative. This follows our 2010 paper (Improving the performance of the Roundtable on Sustainable Oil Palm for nature conservation) in Conservation Biology.

—

Scientists Statement on the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil’s Draft Revised Principles and Criteria for Public Consultation – November 2012

As leading scientists with prominent academic and research institutions around the world, we write to encourage the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) to use this review of the RSPO Principles and Criteria as an opportunity to ensure that RSPO-certified sustainable palm oil is grown in a manner that protects tropical forests and the health of our planet. We applaud the RSPO for having strong social and environmental standards, but palm oil cannot be considered sustainable without also having greenhouse gas standards. Nor can it be considered sustainable if it drives species to extinction.

Tropical forests are critical ecosystems that must be conserved. They are home to millions of plant and animal species, are essential for local water-cycling, and store vast amounts of carbon. When they are cleared, biodiversity is lost and the carbon is released into the atmosphere as carbon dioxide, a greenhouse gas that drives climate change.

Moreover, tropical areas with peat soils store even larger amounts of carbon and when water is drained and the soils exposed, carbon is released into the atmosphere for several decades, driving climate changei. In addition, peat exposed to water in drainage canals may decay anaerobically, producing methane – a greenhouse more potent than carbon dioxide.

Palm oil production continues to increase in the tropics, and in some cases that production is directly driving tropical deforestation and the destruction of peatlandsii. Given the large carbon footprint and irreparable biodiversity loss such palm oil production cannot be considered sustainable. Read the rest of this entry »

Here at ConservationBytes.com, My contributors and I have highlighted the important regulating role of predators in myriad systems. We have written extensively on the mesopredator release concept applied to dingos, sharks and coyotes, but we haven’t really expanded on the broader role of predators in more complex systems.

This week comes an elegant experimental study (and how I love good experimental evidence of complex ecological processes and how they affect population persistence and ecosystem stability, resilience and productivity) demonstrating, once again, just how important predators are for healthy ecosystems. Long story short – if your predators are not doing well, chances are the rest of the ecosystem is performing poorly.

Today’s latest evidence comes from on an inshore marine system in Ireland involving crabs (Carcinus maenas), whelks (Nucella lapillus), gastropd grazers (Patella vulgata, Littorina littorea and Gibbula umbilicalis), mussels (Mytilus edulis) and macroalgae. Published in Journal of Animal Ecology, O’Connor and colleagues’ paper (Distinguishing between direct and indirect effects of predators in complex ecosystems) explains how their controlled experimental removals of different combinations of predators (crabs & whelks) and their herbivore prey (mussels & gastropods) affected primary producer (macroalgae) diversity and cover (see Figure below and caption from O’Connor et al.). Read the rest of this entry »

Left: An Anatolian shepherd (a Turkish breed improved in the USA) guiding a herd of boer goats whose flesh is much appreciated by people in Namibia and South Africa. Right: A cheetah carrying a radio-transmitter, within a project assessing range movements of this feline for the Cheetah Conservation Fund. Cheetahs refrain from moving close to the herds when the latter are looked after by the guardian dogs. Photos courtesy of Laurie Marker.

Another corker from Salva. He’s chosen a topic this week that’s near and dear to my brain – the conservation of higher-order predators. As ConBytes readers will know, we’ve talked a lot about human-predator conflict and the inevitable losers in that battle – the (non-human) predators. From dingos to sharks, predator xenophobia is just another way we weaken ecosystems and ultimately harm ourselves.

—

Rural areas devoted to livestock are part of the natural landscape, so it is inevitable (as well as natural) that predators, livestock and humans interact in such a mosaic of bordering habitats. However, their coexistence remains an unresolved conservation problem.

When two species, people, political parties, enterprises… want the same thing, they either share it (if possible) or one side eliminates the competitor. The fact that proteins are part of the diet of humans and other carnivore species has resulted in a trophic drama that goes back millennia. Nowadays, predators like eagles, coyotes, lions, wolves and raccoons are credited for attacks on cattle and poultry (and people!) in all continents. This global problem is not only economic, but interlaces culture, emotion, policy and sanitation (1-4). For instance, some carnivores are reservoirs of cattle diseases and contribute to pathogen dispersal (5, 6).

Management options

Managers of natural resources have implemented three strategies to handle these sorts of issues for livestock breeders in general (7). Those strategies can be complementary or exclusive on a case-by-case basis, and are chosen following cost-benefit assessments and depending on the conservation status of the predator species involved. (i) ‘Eradication’ aims to eliminate the predator, which is regarded as noxious and worthless. (ii) ‘Regulation’ allows controlled takes under quota schemes, normally for pre-defined locations, dates and killing methods. ‘Preservation’ is applied in protected areas and/or for rare or endangered species, and often requires monitoring and measures set to prevent illegal harvest or trade. Additionally, many livestock breeders receive money to compensate losses to predators (8).

Many experts now advocate non-lethal (preventive) measures that modify the behaviour of people, livestock or predators (2, 7). The use of livestock-guarding dogs is one of those preventive measures (9). As an example, Laurie Marker (director of the Cheetah Conservation Fund) et al. (10) studied the use of 117 Anatolian shepherds adopted by Namibian rangers between 1995 and 2002 (Fig. 1). In this African country, cheetahs (Acinonyx jubatus) selectively forage on small-sized cattle and juveniles. Despite this feline being protected nationally, Namibian laws authorise rangers to shoot cheetahs in situations of risk to people and their properties, with more than 6,000 cheetahs having been killed in the 1980s alone (11). Through face-to-face interviews, Marker found that since the arrival of the Anatolian shepherds, > 70 % of the rangers perceived a pronounced reduction in cattle mortality (10). Although, the use of livestock-guarding dogs has worked out fine in many places worldwide, it is no panacea. In many other instances, the dogs dissuade some predator species and not others from harassing the livestock, or are only effective in combination with other measures (7, 9). Read the rest of this entry »

I am a forest officer from India. I want to narrate a story. No, my story is not about elephants or tigers or snakes. Those stories about India are commonplace. I wish to narrate a simple story about people, the least-known part of the marathon Indian fable.

I am a forest officer from India. I want to narrate a story. No, my story is not about elephants or tigers or snakes. Those stories about India are commonplace. I wish to narrate a simple story about people, the least-known part of the marathon Indian fable.

Humans are said to have arrived in India very early in world civilisation. Some were raised here from the seed of their ancestors; others migrated here from all over the world. Over the centuries these people occupied every inch of soil that could support life. The population of India today is 1.2 billion. Each year, India’s population increases by a number nearly equal to the complete population of Australia. Such a prolific growth of numbers is easy to explain; the fertile soil, ample water and tropical warmth of India support the growth of all life forms.

Not all numbers are great, however, and big numbers sometimes exact the price from the wrong persons.

This is my story.

I went to work in the state of Meghalaya in north-eastern India. Pestilence, floods and dense vegetation have made north-eastern India a most inhospitable place. Population is scanty by Indian standards. Life does not extend much beyond the basic chores of finding food and hearth. In the hills, far away from the bustle of modern civilisation, primitive tribal families practice agriculture in its most basic form. Fertilisers are unknown to them, so they cultivate a parcel of land until it loses its fertility, ultimately abandoning it to find other arable land. When the original parcel has finally recovered its fertility after a few years, they move back. It is a ceaseless cycle of migrating back and forth – the so-called practice known as ‘shifting cultivation’. Ginger, peas, pumpkin, brinjal and sweet potato can be seen growing on numerous slopes in the Garo Hills of Meghalaya beside the huts of the farmers built on stilts, with chickens roosting below.

Photo credit: http://tarumitra.wordpress.com/

When I reached Meghalaya and looked about at the kind of world I had never seen before, I admit that I found the tribal folk a little strange. They lived in a way that would have appeared bizarre to a modern community. The people did not seem to know how many centuries had passed them by. For me as a forest officer, what looked worst was that that these people appeared to have no comprehension of the value of forests for the planet. They built their huts with wood. They cooked on firewood. Most of their implements were made of wood. A whole tree would be cut and thrown across the banks to make a bridge over a stream. Above all, their crazy practice of shifting cultivation would ultimately remove all the remaining forest.

I decided my main job in this place was to save the forest from its own people, and we enforced Indian laws to preserve the forests.

On one occasion my staff saw a young local man running with an illegally obtained log of wood and started to chase him, waving their guns in the air to scare him. He ran barefoot amid dense bushes a long distance before we managed to apprehend him. I had bruises on my arms and a leech hanging from my armpit drinking my blood by the time the race was over. I admit that in my anger at the time, I wanted to impale the man to the earth at the spot where he had cut down the tree. It was not the leeches and the bruises that angered me. The tree he was carrying was (until quite recently) in perfect condition.

But Meghalaya isn’t populated solely by subsistence-farming villagers – there are also a few successful traders originally from big cities who have settled in this economically depressed region. They dress smartly and speak impeccable English. At the time, I remembered wondering how these more sophisticated types could be maintaining their relatively lavish lifestyles among the poor villagers who walked barefoot in the dense forests. On a couple of occasions I dropped in at the home of a prominent trader. He hosted me graciously in his beautiful home. I admit that I enjoyed these visits because they were my only link to the civilisation I had become used to prior to moving to Meghalaya. But I never visited the home of any tribal villager, for what could I talk to them about anyway?

Through fraudulent permits and similar tactics, organized crime profits significantly from illegal logging. jcoterhals

By Bill Laurance, James Cook University

Illegal logging is booming, as criminal organisations tighten their grip on this profitable global industry. Hence, it comes just in the nick of time that Australia, after years of debate, is on the verge of passing an anti-logging bill.

Illegal logging is an international scourge, and increasingly an organised criminal activity. It robs developing nations of vital revenues while promoting corruption and murder. It takes a terrible toll on the environment, promoting deforestation, loss of biodiversity and harmful carbon emissions at alarming rates.

Moreover, the flood of illegal timber makes it much harder for legitimate timber producers. The vast majority of those in Australia and New Zealand have difficulty competing in domestic and international markets. That’s one reason that many major Aussie retail chains and brands, such as Bunnings, Ikea-Australia, Timber Queensland, and Kimberly-Clark, are supporting the anti-illegal logging bill.

Illegal logging thrives because it’s lucrative. A new report by Interpol and the United Nations Environment Programme, “Green Carbon, Black Trade”, estimates the economic value of illegal logging and wood processing to range from $30 billion to $100 billion annually. That’s a whopping figure — constituting some 10-30% of the global trade in wood products.

Illegal logging plagues some of the world’s poorest peoples, many of whom live in tropical timber-producing countries. According to a 2011 study by the World Bank, two-thirds of the world’s top tropical timber-producing nations are losing at least half of their timber to illegal loggers. In some developing countries the figure approaches 90%.

Many nations export large quantities of timber or wood products into Australia. These include Indonesia, Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands, all of which are suffering heavily from illegal logging. Many Chinese-made wood and paper imports also come from illegal timber. Indonesian President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono has been pleading with timber-importing nations like Australia to help it combat illegal logging, which costs the nation billions of dollars annually in lost revenues.

The new Interpol report shows just how devious illegal loggers are becoming. It details more than 30 different ways in which organised criminal gangs stiff governments of revenues and launder their ill-gotten gains.

The variety of tactics used is dizzying. These tactics include falsifying logging permits and using bribery to obtain illegal logging permits, logging outside of timber concessions, hacking government websites to forge transportation permits, and laundering illegal timber by mixing it in with legal timber supplies.

The good news however, is that improving enforcement is slowly making things tougher for illegal loggers.

Accustomed to dealing with criminal enterprises that transcend international borders, Interpol is bringing a new level of sophistication to the war on illegal logging. This is timely because most current efforts to fight illegal logging – such as the European Union’s Forest Law and various timber eco-certification schemes – just aren’t designed to combat organised crime, corruption and money laundering.

The Interpol report urges a multi-pronged approach to fight illegal loggers. A key element of this is anti-logging legislation that makes it harder for timber-consuming nations and their companies to import ill-gotten timber and wood products. Read the rest of this entry »

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species uses 5 quantitative criteria to allocate species to 9 categories of extinction risk. The criteria are based on ecological theory (1, 2), and are therefore subject to modification and critique. With pros and cons (3-6), and intrigues (7, 8), the list has established itself as an important tool for assessing the state of biodiversity globally and, more recently, regionally.

—

We all carry codes of some sort; that is, unique alphanumeric labels identifying our membership in a collectivity. Some of those codes (e.g., a videoclub customer number) make sense only locally, some do internationally (e.g., passport number). Species are also members of the club of biodiversity and, by virtue of our modern concern for their conservation, the status of many taxa has been allocated to alphanumeric categories under different rationales such as extinction risk or trading schemes (5, 9-13). Contradiction emerges when taxa might be threatened locally but not internationally, or vice versa.

In the journal Biological Conservation, a recent paper (14) has echoed the problem for the seagrass Zostera muelleri. This marine phanerogam occurs in Australia, New Zealand and Papua New Guinea, and is listed as “Least Concern” (LC) with “Stable” population trend by the IUCN. Matheson et al. (14) stated that such status neglects the “substantial loss” of seagrass habitats in New Zealand, and that the attribution of “prolific seed production” to the species reflects the IUCN assessment bias towards Australian populations. The IUCN Seagrass Red List Authority, Fred Short, responded (15) that IUCN species ratings indicate global status (i.e., not representative for individual countries) and that, based on available quantitative data and expert opinion, the declines of Z. muelleri are localised and offset by stable or expanding populations throughout its range. Read the rest of this entry »

There’s nothing like a bit of good, intelligent and respectful debate in science.

After the publication in Nature of our paper on tropical protected areas (Averting biodiversity collapse in tropical forest protected areas), some interesting discussion has ensued regarding some of our assumptions and validations.

As is their wont, Nature declined to publish these comments (and our responses) in the journal itself, but the new commenting feature at Nature.com allowed the exchange to be published online with the paper. Cognisant that probably few people will read this exchange, Bill Laurance and I decided to reproduce them here in full for your intellectual pleasure. Any further comments? We’d be keen to hear them.

—

COMMENT #1 (by Hari Sridhar of the Centre for Ecological Sciences at the Indian Institute of Science in Bangalore)

In this paper, Laurance and co-authors have tapped the expert opinions of ‘veteran field biologists and environmental scientists’ to understand the health of protected areas in the tropics worldwide. This is a novel and interesting approach and the dataset they have gathered is very impressive. Given that expert opinion can be subject to all kinds of biases and errors, it is crucial to demonstrate that expert opinion matches empirical reality. While the authors have tried to do this by comparing their results with empirical time-series datasets, I argue that their comparison does not serve the purpose of an independent validation.

Using 59 available time-series datasets from 37 sources (journal papers, books, reports etc.), the authors find a fairly good match between expert opinion and empirical data (in 51/59 cases, expert opinion matched empirically-derived trend). For this comparison to serve as an independent validation, it is crucial that the experts were unaware of the empirical trends at the time of the interviews. However, this is unlikely to be true because, in most cases, the experts themselves were involved in the collection of the time-series datasets (at least 43/59 to my knowledge, from a scan of references in Supplementary Table 1). In other words, the same experts whose opinions were being validated were involved in collection of the data used for validation.

—

OUR RESPONSE (William F. Laurance, Corey J. A. Bradshaw, Susan G. Laurance)

Sridhar raises a relevant point but one that, on careful examination, does not weaken our validation analysis. Read the rest of this entry »

I have, on many occasions, been faced with a difficult question after giving a public lecture. The question is philosophical in nature (and I was never very good at philosophy – just ask my IB philosophy teacher), hence its unusually complicated implications. The question goes something like this:

I have, on many occasions, been faced with a difficult question after giving a public lecture. The question is philosophical in nature (and I was never very good at philosophy – just ask my IB philosophy teacher), hence its unusually complicated implications. The question goes something like this:

Given what you know about the state of the world – the decline in biodiversity, ecosystem services and our own health and welfare – how do you manage to get out of bed in the morning and go to work?

Yes, I can be a little, shall we say, ‘gloomy’ when I give a public lecture; I don’t tend to hold back much when it comes to just how much we’ve f%$ked over our only home, or why we continue to shit in our own (or in many cases, someone else’s) kitchen. It’s not that I get some sick-and-twisted pleasure out of seeing people in the front row shake their heads and ‘tsk-tsk’ their way through my presentation, but I do feel that as an ‘expert’ (ascribe whatever meaning to that descriptor you choose), I have a certain duty to inform non-experts about what the data say.

And if you’ve read even a handful of the posts on this site, you’ll understand that picture I paint isn’t full of roses and children’s smiling faces. A quick list of recent posts might remind you:

And so on. I agree – pretty depressing. Read the rest of this entry »

I’ve been meaning to write about this for a while, and now finally I have been given the opportunity to put my ideas ‘down on paper’ (seems like a bit of an old-fashioned expression these days). Now this post might strike some as overly parochial because it concerns the state in which I live, but the concept applies to every jurisdiction that passes laws designed to protect biodiversity. So please look beyond my navel and place the example within your own specific context.

I’ve been meaning to write about this for a while, and now finally I have been given the opportunity to put my ideas ‘down on paper’ (seems like a bit of an old-fashioned expression these days). Now this post might strike some as overly parochial because it concerns the state in which I live, but the concept applies to every jurisdiction that passes laws designed to protect biodiversity. So please look beyond my navel and place the example within your own specific context.

As CB readers will appreciate, I am firmly in support of the application of conservation triage – that is, the intelligent, objective and realistic way of attributing finite resources to minimise extinctions for the greatest number of (‘important’) species. Note that deciding which species are ‘important’ is the only fly in the unguent here, with ‘importance’ being defined inter alia as having a large range (to encompass many other species simultaneously), having an important ecological function or ecosystem service, representing rare genotypes, or being iconic (such that people become interested in investing to offset extinction.

But without getting into the specifics of triage per se, a related issue is how we set environmental policy targets. While it’s a lovely, utopian pipe dream that somehow our consumptive 7-billion-and-growing human population will somehow retract its massive ecological footprint and be able to save all species from extinction, we all know that this is irrevocably fantastical.

So when legislation is passed that is clearly unattainable, why do we accept it as realistic? My case in point is South Australia’s ‘No Species Loss Strategy‘ (you can download the entire 7.3 Mb document here) that aims to

“…lose no more species in South Australia, whether they be on land, in rivers, creeks, lakes and estuaries or in the sea.”

When I first learned of the Strategy, I instantly thought to myself that while the aims are laudable, and many of the actions proposed are good ones, the entire policy is rendered toothless by the small issue of being impossible. Read the rest of this entry »

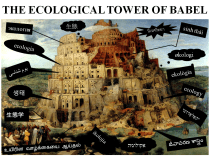

The term ‘ecology’ in 16 different languages overlaid on the oil on board ‘The Tower of Babel’ by Flemish Renaissance painter Pieter Bruegel the Elder (1563).

In his song ‘Balada de Babel’, the Spanish artist Luis Eduardo Aute sings several lyrics in unison with the same melody. The effect is a wonderful mess. This is what the scientific literature sounds like when authors generate synonymies (equivalent meaning) and polysemies (multiple meanings), or coin terms to show a point of view. In our recent paper published in Oecologia, we illustrate this problem with regard to ‘density dependence’: a key ecological concept. While the biblical reference is somewhat galling to our atheist dispositions, the analogy is certainly appropriate.

—

A giant shoal of herring zigzagging in response to a predator; a swarm of social bees tending the multitudinous offspring of their queen; a dense pine forest depriving its own seedlings from light; an over-harvested population of lobsters where individuals can hardly find reproductive mates; pioneering strands of a seaweed colonising a foreign sea after a transoceanic trip attached to the hulk of boat; respiratory parasites spreading in a herd of caribou; or malaria protozoans making their way between mosquitoes and humans – these are all examples of population processes that operate under a density check. The number of individuals within those groups of organisms determines their chances for reproduction, survival or dispersal, which we (ecologists) measure as ‘demographic rates’ (e.g., number of births per mother, number of deaths between consecutive years, or number of immigrants per hectare).

In ecology, the causal relationship between the size of a population and a demographic rate is known as ‘density dependence’ (DD hereafter). This relationship captures the pace at which a demographic rate changes as population size varies in time and/or space. We use DD measurements to infer the operation of social and trophic interactions (cannibalism, competition, cooperation, disease, herbivory, mutualism, parasitism, parasitoidism, predation, reproductive behaviour and the like) between individuals within a population1,2, because the intensity of these interactions varies with population size. Thus, as a population of caribou expands, respiratory parasites will have an easier job to disperse from one animal to another. As the booming parasites breed, increased infestations will kill the weakest caribou or reduce the fertility of females investing too much energy to counteract the infection (yes, immunity is energetically costly, which is why you get sick when you are run down). In turn, as the caribou population decreases, so does the population of parasites3. In cybernetics, such a toing-and-froing is known as ‘feedback’ (a system that controls itself, like a thermostat controls the temperature of a room) – a ‘density feedback’ (Figure 1) is the kind we are highlighting here. Read the rest of this entry »

While in transit between tropical and temperate Australia, here’s the latest batch of 6 biodiversity cartoons (see full stock of previous ‘Cartoon guide to biodiversity loss’ compendia here).

—

California sea lion at Bonneville fish ladder. Credit: U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

As if to mimic the weirder and weirder weather human-caused climate disruption is cooking up for us, related science stories seem to come in floods and droughts. Yes, research trends become fashionable too (imagine a science fashion show? – but I digress…).

Only yesterday, the ABC published an opinion piece on the controversies surrounding which species we call ‘native’ and ‘invasive’ (based on a recent paper published in Global Ecology and Biogeography), and in June this year, Salvador Herrando-Pérez wrote a great little article on the topic entitled “The invader’s double edge“.

Then today, I received a request to publish a guest post here on ConservationBytes.com from Lauren Kuehne, a research scientist in Julian Olden‘s lab at the University of Washington in Seattle. The topic? Why, the controversies surrounding invasive species, of course! Lauren’s following article demonstrates yet again that it’s not that simple.

—

A drawback to the attention garnered by high-profile invasive species is the tendency to infer that every non-native species is bad news, the inverse assumption being that all native species must be ‘good’. While this storyline works well for Hollywood films and faerie tales, in ecology the truth is rarely that simple. A new review article in the September issue of Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, describes the challenges and heartbreaks when native species run amok in the sense of having negative ecological impacts we typically associate with non-native species. Examples in the paper range from unchecked expansions of juniper trees in sagebrush ecosystems with wildfire suppression, to overgrazing by elk (wapiti) released from predation following the removal of wolves and mountain lions. Read the rest of this entry »

Rocking the scientific boat

14 12 2012© C. Simpson

One thing that has simultaneously amused, disheartened, angered and outraged me over the past decade or so is how anyone in their right mind could even suggest that scientists band together into some sort of conspiracy to dupe the masses. While this tired accusation is most commonly made about climate scientists, it applies across nearly every facet of the environmental sciences whenever someone doesn’t like what one of us says.

First, it is essential to recognise that we’re just not that organised. While I have yet to forget to wear my trousers to work (I’m inclined to think that it will happen eventually), I’m still far, far away from anything that could be described as ‘efficient’ and ‘organised’. I can barely keep it together as it is. Such is the life of the academic.

More importantly, the idea that a conspiracy could form among scientists ignores one of the most fundamental components of scientific progress – dissension. And hell, can we dissent!

Yes, the scientific approach is one where successive lines of evidence testing hypotheses are eventually amassed into a concept, then perhaps a rule of thumb. If the rule of thumb stands against the scrutiny of countless studies (i.e., ‘challenges’ in the form of poison-tipped, flaming literary arrows), then it might eventually become a ‘theory’. Some theories even make it to become the hallowed ‘law’, but that is very rare indeed. In the environmental sciences (I’m including ecology here), one could argue that there is no such thing as a ‘law’.

Well-informed non-scientists might understand, or at least, appreciate that process. But few people outside the sciences have even the remotest clue about what a real pack of bastards we can be to each other. Use any cliché or descriptor you want – it applies: dog-eat-dog, survival of the fittest, jugular-slicing ninjas, or brain-eating zombies in lab coats.

Read the rest of this entry »

Share:

Comments : 10 Comments »

Tags: comments, conspiracy, peer review, publishing, referees, responses, scientific process, Scientist

Categories : climate change, conservation, conservation biology, environmental science, fragmentation, habitat loss, minimum viable population, mvp, research, science, scientific publishing, scientific writing