The other night I had the pleasure of dining with the former Australian Democrats leader and senator, Dr John Coulter, at the home of Dr Paul Willis (Director of the Royal Institution of Australia). It was an enlightening evening.

The other night I had the pleasure of dining with the former Australian Democrats leader and senator, Dr John Coulter, at the home of Dr Paul Willis (Director of the Royal Institution of Australia). It was an enlightening evening.

While we discussed many things, the 84 year-old Dr Coulter showed me a rather amazing advert that he and several hundred other scientists, technologists and economists constructed to alert the leaders of Australia that it was heading down the wrong path. It was amazing for three reasons: (i) it was written in 1971, (ii) it was published in The Australian, and (iii) it could have, with a few modifications, been written for today’s Australia.

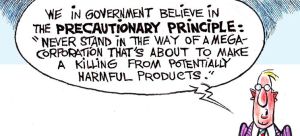

If you’re an Australian and have even a modicum of environmental understanding, you’ll know that The Australian is a Murdochian rag infamous for its war on science and reason. Even I have had a run-in with its outdated, consumerist and blinkered editorial board. You certainly wouldn’t find an article like Dr Coulter’s in today’s Australian.

More importantly, this 44 year-old article has a lot today that is still relevant. While the language is a little outdated (and sexist), the grammar could use a few updates, and there are some predictions that clearly never came true, it’s telling that scientists and others have been worrying about the same things for quite some time.

In reading the article (reproduced below), one could challenge the authors for being naïve about how society can survive and even prosper despite a declining ecological life-support system. As I once queried Paul Ehrlich about some of his particularly doomerist predictions from over 50 years ago, he politely pointed out that much of what he predicted did, in fact, come true. There are over 1 billion people today that are starving, and another billion or so that are malnourished; combined, this is greater than the entire world population when Paul was born.

So while we might have delayed the crises, we certainly haven’t averted them. Technology does potentially play a positive role, but it can also increase our short-term carrying capacity and buffer the system against shocks. We then tend to ignore the indirect causes of failures like wars, famines and political instability because we do not recognise the real drivers: resource scarcity and ecosystem malfunction.

Australia has yet to learn its lesson.

—

To Those Who Shape Australia’s Destiny

We believe that western technological society has ignored two vital facts: Read the rest of this entry »

A perennial lament of nearly every conservation scientist — at least at some point (often later in one’s career) — is that the years of blood, sweat and tears spent to obtain those precious results count for nought in terms of improving real biodiversity conservation.

A perennial lament of nearly every conservation scientist — at least at some point (often later in one’s career) — is that the years of blood, sweat and tears spent to obtain those precious results count for nought in terms of improving real biodiversity conservation.