Thermal microhabitats are often uncoupled from above-ground air temperatures. A study focused on small frogs and lizards from the Philippines demonstrates that the structural complexity of tropical forests hosts a diversity of microhabitats that can reduce the exposure of many cold-blooded animals to anthropogenic climate warming.

Reproductive pair of the Luzon forest frogs Platymantis luzonensis (upper left), a IUCN near-threatened species restricted to < 5000 km2 of habitat. Lower left: the yellow-stripped slender tree lizard Lipinia pulchella, a IUCN least-concerned species. Both species have body lengths < 6 cm, and are native to the tropical forests of the Philippines. Right panels, top to bottom: four microhabitats monitored by Scheffers et al. (2), namely ground vegetation, bird’s nest ferns, phytotelmata, and fallen leaves above ground level. Photos courtesy of Becca Brunner (Platymantis), Gernot Kunz (Lipinia), Stephen Zozaya (ground vegetation) and Brett Scheffers (remaining habitats).

If you have ever entered a cave or an old church, you will be familiar with its coolness even in the dog days of summer. At much finer scales, from centimetres to millimetres, this ‘cooling effect’ occurs in complex ecosystems such as those embodied by tropical forests. The fact is that the life cycle of many plant and animal species depends on the network of microhabitats (e.g., small crevices, burrows, holes) interwoven by vegetation structures, such as the leaves and roots of an orchid epiphyte hanging from a tree branch or the umbrella of leaves and branches of a thick bush.

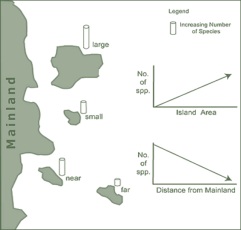

Much modern biogeographical research addressing the effects of climate change on biodiversity is based on macroclimatic data of temperature and precipitation. Such approaches mostly ignore that microhabitats can warm up or cool down in a fashion different from that of local or regional climates, and so determine how species, particularly ectotherms, thermoregulate (1). To illustrate this phenomenon, Brett Scheffers et al. (2) measured the upper thermal limits (typically known as ‘critical thermal maxima’ or CTmax) of 15 species of frogs and lizards native to the tropical forest of Mount Banahaw, an active volcano on Luzon (The Philippines). The > 7000 islands of this archipelago harbour > 300 species of amphibians and reptiles (see video here), with > 100 occurring in Luzon (3).

I believe it is important to clarify a few things about the job advertisement that we are re-opening.

I believe it is important to clarify a few things about the job advertisement that we are re-opening.

With my new position as

With my new position as  Last year I wrote what has become a highly viewed post here at ConservationBytes.com about the

Last year I wrote what has become a highly viewed post here at ConservationBytes.com about the  Last year we reported

Last year we reported