First batch of six biodiversity cartoons for 2015 (see full stock of previous ‘Cartoon guide to biodiversity loss’ compendia here).

—

First batch of six biodiversity cartoons for 2015 (see full stock of previous ‘Cartoon guide to biodiversity loss’ compendia here).

—

Here are the last 6 biodiversity cartoons for 2014 because, well, why not? (see full stock of previous ‘Cartoon guide to biodiversity loss’ compendia here).

—

Another year, another arbitrary retrospective list – but I’m still going to do it. Based on the popularity of last year’s retrospective list of influential conservation papers as assessed through F1000 Prime, here are 20 conservation papers published in 2014 that impressed the Faculty members.

Another year, another arbitrary retrospective list – but I’m still going to do it. Based on the popularity of last year’s retrospective list of influential conservation papers as assessed through F1000 Prime, here are 20 conservation papers published in 2014 that impressed the Faculty members.

Once again for copyright reasons, I can’t give the whole text but I’ve given the links to the F1000 assessments (if you’re a subscriber) and of course, to the papers themselves. I did not order these based on any particular criterion.

—

Here are 8 more biodiversity cartoons (with a human population focus, given recent events) for your conservation-humour fix (see full stock of previous ‘Cartoon guide to biodiversity loss’ compendia here).

—

Here are 6 more biodiversity cartoons for your conservation-humour fix (see full stock of previous ‘Cartoon guide to biodiversity loss’ compendia here).

—

I’m currently in Cairns at the Association for Tropical Biology and Conservation‘s Annual Conference where scientists from all over the world have amassed for get the latest on tropical ecology and conservation. Unfortunately, all of them have arrived in an Australia different to the one they knew or admired from afar. The environmental devastation unleashed by the stupid policies of the Abbottoir government has attracted the attention and ire of some of the world’s top scientists. This is what they have to say about it (with a little help from me):

I’m currently in Cairns at the Association for Tropical Biology and Conservation‘s Annual Conference where scientists from all over the world have amassed for get the latest on tropical ecology and conservation. Unfortunately, all of them have arrived in an Australia different to the one they knew or admired from afar. The environmental devastation unleashed by the stupid policies of the Abbottoir government has attracted the attention and ire of some of the world’s top scientists. This is what they have to say about it (with a little help from me):

—

ASSOCIATION FOR TROPICAL BIOLOGY AND CONSERVATION

RESOLUTION IN SUPPORT OF STRONGER LAWS FOR CLIMATE-CHANGE MITIGATION AND ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION IN AUSTRALIA

Australia has many trees, amphibians, and reptiles that are unique, being found nowhere else on Earth. Northern Australia contains a disproportionate amount of this biodiversity which occurs in little developed areas, parks and reserves, indigenous titled lands, and community-managed lands.

Whilst Australia’s achievements in protecting some of its remaining native forests, wildlife and wilderness are applauded, some 6 million hectares of forest have been lost since 2000. Existing forest protection will be undermined by weak climate change legislation, and poorly regulated agricultural and urban development.

The Association for Tropical Biology and Conservation (ATBC), the world’s largest organisation dedicated to the study and conservation of tropical ecosystems, is concerned about recent changes in Australia’s environmental regulations, reduced funding for scientific and environmental research, and support for governmental and civil society organisations concerned with the environment. Read the rest of this entry »

Published today on ABC Environment.

—

Greg Hunt, the Coalition Government’s Minister for the Environment, today announced what appears to be one of the only environmental promises kept from their election campaign in 2013: to appoint a Threatened Species Commissioner.

The appointment is unprecedented for Australia – we have never had anything remotely like it in the past. However, I am also confident that this novelty will turn out to be one of the position’s only positives.

My scepticism is not based on my personal political or philosophical perspectives; rather, it arises from Coalition Government’s other unprecedented policies to destroy Australia’s environment. No other government in the last 50 years has mounted such a breath-taking War on the Environment. In the nine month’s since the Abbott Government took control, there has been a litany of backward and dangerous policies, from the well-known axing of the Climate Commission and their push to dump of 3 million tonnes of dredge on the World Heritage Great Barrier Reef, to their lesser-publicised proposals to remove the non-profit tax status of green organisations and kill the Environmental Defenders Office. The Government’s list of destructive, right-wing, anti-environmental policies is growing weekly, with no signs of abatement.

With this background, it should come as no surprise that considerable cynicism is emerging following the Minister’s announcement. Fears that another powerless pawn of the current government appear to have been realised with the appointment of Gregory Andrews as the Commissioner. Mr Andrews is a public servant (ironically from the now-defunct Department of Department of Climate Change and Energy Efficiency) and former diplomat who has some minor infamy regarding contentious comments he made in 2006 when acting as a senior bureaucrat in Mal Brough’s Department of Indigenous Affairs. Apart from Mr Gregory’s general lack of specific expertise in species recovery, the choice appears to be neutral at best.

More importantly, the major limitation of the Commissioner to realise real benefits for Australian biodiversity is the position’s total lack of political power. Greg Hunt himself confirmed that Mr Andrews will not be able to affect government policy other than ‘encourage’ cooperation between states and environmental groups. The position also comes with a (undisclosed) funding guarantee of only one year, which makes it sound more like an experiment in public relations than effective environmental policy. Read the rest of this entry »

Some of you who are familiar with my colleagues’ and my work will know that we have been investigating the minimum viable population size concept for years (see references at the end of this post). Little did I know when I started this line of scientific inquiry that it would end up creating more than a few adversaries.

Some of you who are familiar with my colleagues’ and my work will know that we have been investigating the minimum viable population size concept for years (see references at the end of this post). Little did I know when I started this line of scientific inquiry that it would end up creating more than a few adversaries.

It might be a philosophical perspective that people adopt when refusing to believe that there is any such thing as a ‘minimum’ number of individuals in a population required to guarantee a high (i.e., almost assured) probability of persistence. I’m not sure. For whatever reason though, there have been some fierce opponents to the concept, or any application of it.

Yet a sizeable chunk of quantitative conservation ecology develops – in various forms – population viability analyses to estimate the probability that a population (or entire species) will go extinct. When the probability is unacceptably high, then various management approaches can be employed (and modelled) to improve the population’s fate. The flip side of such an analysis is, of course, seeing at what population size the probability of extinction becomes negligible.

‘Negligible’ is a subjective term in itself, just like the word ‘very‘ can mean different things to different people. This is why we looked into standardising the criteria for ‘negligible’ for minimum viable population sizes, almost exactly what the near universally accepted IUCN Red List attempts to do with its various (categorical) extinction risk categories.

But most reasonable people are likely to agree that < 1 % chance of going extinct over many generations (40, in the case of our suggestion) is an acceptable target. I’d feel pretty safe personally if my own family’s probability of surviving was > 99 % over the next 40 generations.

Some people, however, baulk at the notion of making generalisations in ecology (funny – I was always under the impression that was exactly what we were supposed to be doing as scientists – finding how things worked in most situations, such that the mechanisms become clearer and clearer – call me a dreamer).

So when we were attacked in several high-profile journals, it came as something of a surprise. The latest lashing came in the form of a Trends in Ecology and Evolution article. We wrote a (necessarily short) response to that article, identifying its inaccuracies and contradictions, but we were unable to expand completely on the inadequacies of that article. However, I’m happy to say that now we have, and we have expanded our commentary on that paper into a broader review. Read the rest of this entry »

This is a little bit of a bandwagon – the ‘retrospective’ post at the end of the year – but this one is not merely a rehash I’ve stuff I’ve already covered.

This is a little bit of a bandwagon – the ‘retrospective’ post at the end of the year – but this one is not merely a rehash I’ve stuff I’ve already covered.

I decided that it would be worthwhile to cover some of the ‘big’ conservation papers of 2013 as ranked by F1000 Prime. For copyright reasons, I can’t divulge the entire synopsis of each paper, but I can give you a brief run-down of the papers that caught the eye of fellow F1000 faculty members and me. If you don’t subscribe to F1000, then you’ll have to settle with my briefest of abstracts.

In no particular order then, here are some of the conservation papers that made a splash (positively, negatively or controversially) in 2013:

Chiew Larn Reservoir is surrounded by Khlong Saeng Wildlife Sanctuary and Khao Sok National Park, which together make up part of the largest block of rainforest habitat in southern Thailand (> 3500 km2). Photo: Antony Lynam

One of the perennial and probably most controversial topics in conservation ecology is when is something “too small’. By ‘something’ I mean many things, including population abundance and patch size. We’ve certainly written about the former on many occasions (see here, here, here and here for our work on minimum viable population size), with the associated controversy it elicited.

Now I (sadly) report on the tragedy of the second issue – when is a habitat fragment too small to be of much good to biodiversity?

Published today in the journal Science, Luke Gibson (of No substitute for primary forest fame) and a group of us report disturbing results about the ecological meltdown that has occurred on islands created when the Chiew Larn Reservoir of southern Thailand was flooded nearly 30 years ago by a hydroelectric dam.

As is the case in many parts of the world (e.g., Three Gorges Dam, China), hydroelectric dams can cause major ecological problems merely by flooding vast areas. In the case of Charn Liew, co-author Tony Lynam of Wildlife Conservation Society passed along to me a bit of poignant and emotive history about the local struggle to prevent the disaster.

“As the waters behind the dam were rising in 1987, Seub Nakasathien, the Superintendent of the Khlong Saeng Wildlife Sanctuary, his staff and conservationist friends, mounted an operation to capture and release animals that were caught in the flood waters.

It turned out to be distressing experience for all involved as you can see from the clips here, with the rescuers having only nets and longtail boats, and many animals dying. Ultimately most of the larger mammals disappeared quickly from the islands, leaving just the smaller fauna.

Later Seub moved to Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary and fought an unsuccessful battle with poachers and loggers, which ended in him taking his own life in despair in 1990. A sad story, and his friend, a famous folk singer called Aed Carabao, wrote a song about Seub, the music of which plays in the video. Read the rest of this entry »

Today we announced a HEAP of positions in our Global Ecology Lab for hot-shot, up-and-coming ecologists. If you think you’ve got what it takes, I encourage you to apply. The positions are all financed by the Australian Research Council from grants that Barry Brook, Phill Cassey, Damien Fordham and I have all been awarded in the last few years. We decided to do a bulk advertisement so that we maximise the opportunity for good science talent out there.

We’re looking for bright, mathematically adept people in palaeo-ecology, wildlife population modelling, disease modelling, climate change modelling and species distribution modelling.

The positions are self explanatory, but if you want more information, just follow the links and contacts given below. For my own selfish interests, I provide a little more detail for two of the positions for which I’m directly responsible – but please have a look at the lot.

Good luck!

—

Job Reference Number: 17986 & 17987

The world-leading Global Ecology Group within the School of Earth and Environmental Sciences currently has multiple academic opportunities. For these two positions, we are seeking a Postdoctoral Research Associate and a Research Associate to work in palaeo-ecological modelling. Read the rest of this entry »

Published simultaneously in The Conversation.

—

On Friday, March 15 in Washington DC, National Geographic and TEDx are hosting a day-long conference on species-revival science and ethics. In other words, they will be debating whether we can, and should, attempt to bring extinct animals back to life – a concept some call “de-extinction”.

The debate has an interesting line-up of ecologists, geneticists, palaeontologists (including Australia’s own Mike Archer), developmental biologists, journalists, lawyers, ethicists and even artists. I have no doubt it will be very entertaining.

But let’s not mistake entertainment for reality. It disappoints me, a conservation scientist, that this tired fantasy still manages to generate serious interest. I have little doubt what the ecologists at the debate will conclude.

Once again, it’s important to discuss the principal flaws in such proposals.

Put aside for the moment the astounding inefficiency, the lack of success to date and the welfare issues of bringing something into existence only to suffer a short and likely painful life. The principal reason we should not even consider the technology from a conservation perspective is that it does not address the real problem – mainly, the reason for extinction in the first place.

Even if we could solve all the other problems, if there is no place to put these new individuals, the effort and money expended is a complete waste. Habitat loss is the principal driver of species extinction and endangerment. If we don’t stop and reverse this now, all other avenues are effectively closed. Cloning will not create new forests or coral reefs, for example. Read the rest of this entry »

I’ve written before about how we should all be substantially more concerned about the future than what we as a society appear to be. Climate disruption is society’s enemy number one, especially considering that:

I’ve written before about how we should all be substantially more concerned about the future than what we as a society appear to be. Climate disruption is society’s enemy number one, especially considering that:

That’s probably the most succinct way that I know of describing the mess we are in, which is why I tend to be more of a pragmatic pessimist when it comes to the future. I’ve discussed before how this outlook makes getting on with my job even more important – if I can’t reduce the rate of destruction and give my family a slightly better future in spite of this reality, at least I will damn well die trying. Read the rest of this entry »

It’s human nature to abhor admitting an error, and I’d wager that it’s even harder for the average person (psycho- and sociopaths perhaps excepted) to admit being a bastard responsible for the demise of someone, or something else. Examples abound. Think of much of society’s unwillingness to accept responsibility for global climate disruption (how could my trips to work and occasional holiday flight be killing people on the other side of the planet?). Or, how about fishers refusing to believe that they could be responsible for reductions in fish stocks? After all, killing fish couldn’t possibly …er, kill fish? Another one is that bastion of reverse racism maintaining that ancient or traditionally living peoples (‘noble savages’) could never have wiped out other species.

It’s human nature to abhor admitting an error, and I’d wager that it’s even harder for the average person (psycho- and sociopaths perhaps excepted) to admit being a bastard responsible for the demise of someone, or something else. Examples abound. Think of much of society’s unwillingness to accept responsibility for global climate disruption (how could my trips to work and occasional holiday flight be killing people on the other side of the planet?). Or, how about fishers refusing to believe that they could be responsible for reductions in fish stocks? After all, killing fish couldn’t possibly …er, kill fish? Another one is that bastion of reverse racism maintaining that ancient or traditionally living peoples (‘noble savages’) could never have wiped out other species.

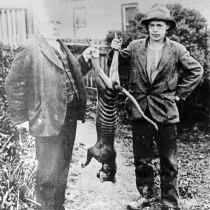

If you’re a rational person driven by evidence rather than hearsay, vested interest or faith, then the above examples probably sound ridiculous. But rest assured, millions of people adhere to these points of view because of the phenomenon mentioned in the first sentence above. With this background then, I introduce a paper that’s almost available online (i.e., we have the DOI, but the online version is yet to appear). Produced by our extremely clever post-doc, Tom Prowse, the paper is entitled: No need for disease: testing extinction hypotheses for the thylacine using multispecies metamodels, and will soon appear in Journal of Animal Ecology.

Of course, I am biased being a co-author, but I think this paper really demonstrates the amazing power of retrospective multi-species systems modelling to provide insight into phenomena that are impossible to test empirically – i.e., questions of prehistoric (and in some cases, even data-poor historic) ecological change. The megafauna die-off controversy is one we’ve covered before here on ConservationBytes.com, and this is a related issue with respect to a charismatic extinction in Australia’s recent history – the loss of the Tasmanian thylacine (‘tiger’, ‘wolf’ or whatever inappropriate eutherian epithet one unfortunately chooses to apply). Read the rest of this entry »

The saying “it isn’t rocket science” is a common cliché in English to state, rather sarcastically, that something isn’t that difficult (with the implication that the person complaining about it, well, shouldn’t). But I really think we should change the saying to “it isn’t ecology”, for ecology is perhaps one of the most complex disciplines in science (whereas rocket science is just ‘complicated’). One of our main goals is to predict how ecosystems will respond to change, yet what we’re trying to simplify when predicting is the interactions of millions of species and individuals, all responding to each other and to their outside environment. It becomes quickly evident that we’re dealing with a system of chaos. Rocket science is following recipes in comparison.

Because of this complexity, ecology is a discipline plagued by a lack of generalities. Few, if any, ecological laws exist. However, we do have an abundance of rules of thumb that mostly apply in most systems. I’ve written about a few of them here on ConservationBytes.com, such as the effect of habitat patch size on species diversity, the importance of predators for maintaining ecosystem stability, and that low genetic diversity doesn’t exactly help your chances of persisting. Another big one is, of course, that in an era of rapid change, big things tend to (but not always – there’s that lovely complexity again) drop off the perch before smaller things do.

The prevailing wisdom is that big species have slower life history rates (reproduction, age at first breeding, growth, etc.), and so cannot replace themselves fast enough when the pace of their environment’s change is too high. Small, rapidly reproducing species, on the other hand, can compensate for higher mortality rates and hold on (better) through the disturbance. Read the rest of this entry »

I’ve been meaning to write about this for a while, and now finally I have been given the opportunity to put my ideas ‘down on paper’ (seems like a bit of an old-fashioned expression these days). Now this post might strike some as overly parochial because it concerns the state in which I live, but the concept applies to every jurisdiction that passes laws designed to protect biodiversity. So please look beyond my navel and place the example within your own specific context.

I’ve been meaning to write about this for a while, and now finally I have been given the opportunity to put my ideas ‘down on paper’ (seems like a bit of an old-fashioned expression these days). Now this post might strike some as overly parochial because it concerns the state in which I live, but the concept applies to every jurisdiction that passes laws designed to protect biodiversity. So please look beyond my navel and place the example within your own specific context.

As CB readers will appreciate, I am firmly in support of the application of conservation triage – that is, the intelligent, objective and realistic way of attributing finite resources to minimise extinctions for the greatest number of (‘important’) species. Note that deciding which species are ‘important’ is the only fly in the unguent here, with ‘importance’ being defined inter alia as having a large range (to encompass many other species simultaneously), having an important ecological function or ecosystem service, representing rare genotypes, or being iconic (such that people become interested in investing to offset extinction.

But without getting into the specifics of triage per se, a related issue is how we set environmental policy targets. While it’s a lovely, utopian pipe dream that somehow our consumptive 7-billion-and-growing human population will somehow retract its massive ecological footprint and be able to save all species from extinction, we all know that this is irrevocably fantastical.

So when legislation is passed that is clearly unattainable, why do we accept it as realistic? My case in point is South Australia’s ‘No Species Loss Strategy‘ (you can download the entire 7.3 Mb document here) that aims to

“…lose no more species in South Australia, whether they be on land, in rivers, creeks, lakes and estuaries or in the sea.”

When I first learned of the Strategy, I instantly thought to myself that while the aims are laudable, and many of the actions proposed are good ones, the entire policy is rendered toothless by the small issue of being impossible. Read the rest of this entry »

While in transit between tropical and temperate Australia, here’s the latest batch of 6 biodiversity cartoons (see full stock of previous ‘Cartoon guide to biodiversity loss’ compendia here).

—

I should have published these ages ago, but like many things I have should have done earlier, I didn’t.

I should have published these ages ago, but like many things I have should have done earlier, I didn’t.

I also apologise for a bit of silence over the past week. After coming back from the ESP Conference in Portland, I’m now back at Stanford University working with Paul Ehrlich trying to finish our book (no sneak peaks yet, I’m afraid). I have to report that we’ve completed about about 75 % it, and I’m starting to feel like the end is in sight. We hope to have it published early in 2013.

So here they are – the latest 9 PhD offerings from us at the Global Ecology Laboratory. If you want to get more information, contact the first person listed as the first supervisor at the end of each project’s description.

—

1. Optimal survey and harvest models for South Australian macropods (I’ve advertised this before, but so far, no takers):

The South Australia Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources (DEWNR) is custodian of a long-term macropod database derived from the State’s management of the commercial kangaroo harvest industry. The dataset entails aerial survey data for most of the State from 1978 to present, annual population estimates, quotas and harvests for three species: red kangaroo (Macropus rufus), western grey kangaroo (Macropus fuliginosus), and the euro (Macropus robustus erubescens).

DEWNR wishes to improve the efficiency of surveys and increase the precision of population estimates, as well as provide a more quantitative basis for setting harvest quotas.

We envisage that the PhD candidate will design and construct population models:

Supervisors: me, A/Prof. Phill Cassey, Dr Damien Fordham, Dr Brad Page (DEWNR), Professor Michelle Waycott (DEWNR).

2. Correcting for the Signor-Lipps effect

The ‘Signor-Lipps effect’ in palaeontology is the notion that the last organism of a given species will never be recorded as a fossil given the incomplete nature of the fossil record (the mirror problem is the ‘Jaanusson effect’, where the first occurrence is delayed past the true time of origination). This problem makes inference about the timing and speed of mass extinctions (and evolutionary diversification events) elusive. The problem is further complicated by the concept known as the ‘pull of the recent’, which states that the more time since an event occurred, the greater the probability that evidence of that event will have disappeared (e.g., erased by erosion, hidden by deep burial, etc.).

In a deep-time context, these problems confound the patterns of mass extinctions – i.e., the abruptness of extinction and the dynamics of recovery and speciation. This PhD project will apply a simulation approach to marine fossil time series (for genera and families, and some individual species) covering the Phanerozoic Aeon, as well as other taxa straddling the K-T boundary (Cretaceous mass extinction). The project will seek to correct for taphonomic biases and assess the degree to which extinction events for different major taxa were synchronous.

The results will also have implications for the famous Sepkoski curve, which describes the apparent logistic increase in marine species diversity over geological time with an approximate ‘carrying capacity’ reached during the Cenozoic. Despite recent demonstration that this increase is partially a taphonomic artefact, a far greater development and validation/sensitivity analysis of underlying statistical models is needed to resolve the true patterns of extinction and speciation over this period.

The approach will be to develop a series of models describing the interaction of the processes of speciation, local extinction and taphonomic ‘erasure’ (pull of the recent) to simulate how these processes interact to create the appearance of growth in numbers of taxa over time (Sepkoski curve) and the abruptness of mass extinction events. The candidate will estimate key parameters in the model to test whether the taphonomic effect is strong enough to be the sole explanation of the apparent temporal increase in species diversity, or whether true diversification accounts for this.

Supervisors: me, Prof. Barry Brook

3. Genotypic relationships of Australian rabbit populations and consequences for disease dynamics

Historical evidence suggests that there were multiple introduction events of European rabbits into Australia. In non-animal model weed systems it is clear that biocontrol efficacy is strongly influenced by the degree of genetic diversity and number of breed variants in the population.

The PhD candidate will build phylogenetic relationships for Australian rabbit populations and develop landscape genetic models for exploring the influence of myxomatosis and rabbit haemorrhagic disease virus (RHDV) on rabbit vital rates (survival, reproduction and dispersal) at regional and local scales. Multi-model synthesis will be used to quantify the relative roles of environment (including climate) and genotype on disease prevalence and virulence in rabbit populations.

Supervisors: A/Prof Phill Cassey, Dr Damien Fordham, Prof Barry Brook Read the rest of this entry »