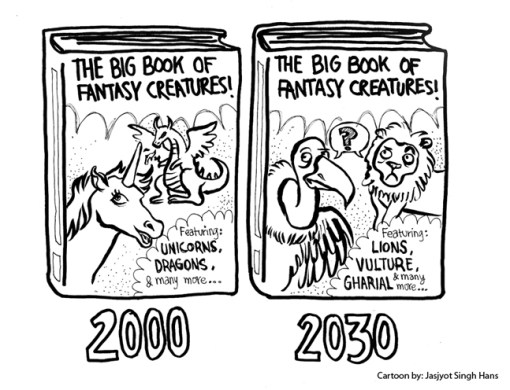

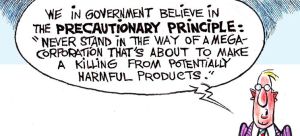

The precautionary principle – the idea that one should adopt an approach that minimises risk – is so ingrained in the mind of the conservation scientist that we often forget what it really means, or the reality of its implementation in management and policy. Indeed, it has been written about extensively in the peer-reviewed conservation literature for over 20 years at least (some examples here, here, here and here).

The precautionary principle – the idea that one should adopt an approach that minimises risk – is so ingrained in the mind of the conservation scientist that we often forget what it really means, or the reality of its implementation in management and policy. Indeed, it has been written about extensively in the peer-reviewed conservation literature for over 20 years at least (some examples here, here, here and here).

From a purely probabilistic viewpoint, the concept is flawlessly logical in most conservation questions. For example, if a particular by-catch of a threatened species is predicted [from a model] to result in a long-term rate of instantaneous population change (r) of -0.02 to 0.01 [uniform distribution], then even though that interval envelops r = 0, one can see that reducing the harvest rate a little more until the lower bound is greater than zero is a good idea to avoid potentially pushing down the population even more. In this way, our modelling results would recommend a policy that formally incorporates the uncertainty of our predictions without actually trying to make our classically black-and-white laws try to legislate uncertainty directly. Read the rest of this entry »