Brent geese flock in the Limfjorden (Denmark) – courtesy of Kevin Clausen. The Brent goose (Branta bernicla) is a migratory goose that breeds in Arctic coasts, as well as in northern Eurasia and the Americas, starting from late May to early June. Adults are about 0.5 m long, weigh some 2 kg and live up to 30 years. Their nests are placed in the ground, where reproductive pairs incubate a single clutch (≤ 5 eggs) for a couple of months. They are herbivores, feeding on algae (mainly Zostera marina in Limfjord) and seagrass in estuaries, fjords, intertidal areas and rocky beaches during fall and winter. During summer they feed on tundra herbs, moss, lichens, as well as aquatic plants in rivers and lakes. The species is ‘Least Concern’ for the IUCN, with a global population at some 600,000 individuals.

Migratory birds synchronise their travel from non-breeding to breeding quarters with the seasonal conditions optimal for reproduction. Above all, they decide when to migrate on the basis of the climate of their wintering areas while they are there. As climate change involves earlier springs in the Arctic but not in the wintering areas, there is a lack of synchronisation that leads to a demographic decline of these birds in the polar regions where they breed.

When I think about how species respond to climate change, the song from the Clash “Should I stay or should I go” comes to mind. As climate changes, species eventually have to face an ultimate choice: (i) stay and adapt to novel conditions or become locally extinct if adaptation fails, (ii) or move to other regions where climatic conditions should be more suitable. Migratory species have to face this decision every time they have to move back and forth from non-breeding to breeding grounds.

Migration is a behavioural strategy shared by different animal groups like sea turtles, mammals, amphibians, insects or birds. Species move from one area to another usually to feed and reproduce in the best climatic conditions possible. For birds, migration is a common phenomenon that typically entails large movements between breeding and wintering grounds. These vertebrates boast some of the longest migratory distances known in the animal kingdom, particularly seabirds like Artic terns, which can complete up to a round-world trip in a single migratory event between the UK and the Antarctic (1). There are several theories about the mechanisms triggering bird migration, including improving body condition and fitness through unexploited resources (2), reducing parasite load (3), minimizing predation risk (4), maximizing day-light (5), or reducing competition (6, 7). Whatever the cause, birds have to decide when the best moment to migrate is, counting only with the (usually climatic) clues they have at the departure site. Read the rest of this entry »

Seeing majestic lions strolling along the Maasai Mara at sunset — a dream vision for many conservationists, but a nightmare for pastoralists trying to keep their cattle safe at night. Fortunately a conservation success story from Kenya, published today in the journal Conservation Evidence, shows that predation of cattle can be reduced by almost 75% by constructing chain-link livestock fences.

Seeing majestic lions strolling along the Maasai Mara at sunset — a dream vision for many conservationists, but a nightmare for pastoralists trying to keep their cattle safe at night. Fortunately a conservation success story from Kenya, published today in the journal Conservation Evidence, shows that predation of cattle can be reduced by almost 75% by constructing chain-link livestock fences.

Apologies for the little gap in my regular posts — I am in the fortunate position of having spent the last three weeks in the beautiful

Apologies for the little gap in my regular posts — I am in the fortunate position of having spent the last three weeks in the beautiful

Last year I

Last year I  Anyone familiar with this blog and our work on energy issues will not be surprised by my sincere

Anyone familiar with this blog and our work on energy issues will not be surprised by my sincere

As have many other scientists, I’ve

As have many other scientists, I’ve

If you live in South Australia, and in Adelaide especially, you would have had to be living under a rock not to have heard of the Great Koala Counts

If you live in South Australia, and in Adelaide especially, you would have had to be living under a rock not to have heard of the Great Koala Counts  Well, the data are in for GKC2 and we need help to analyse them. Just as a little reminder, the GKCs are designed to provide

Well, the data are in for GKC2 and we need help to analyse them. Just as a little reminder, the GKCs are designed to provide

With my new position as

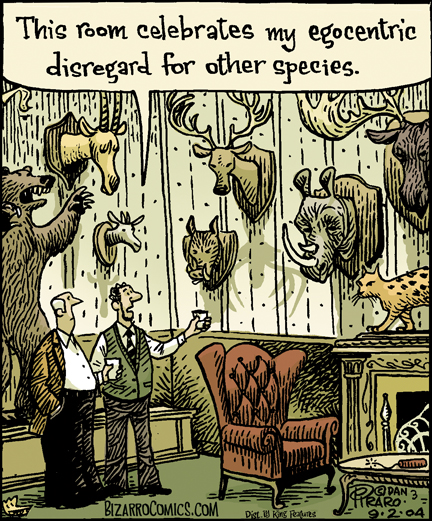

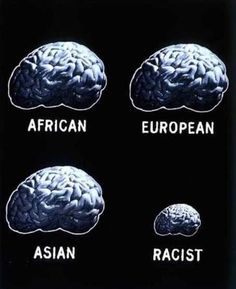

With my new position as  With all the nasty nationalism and xenophobia gurgling nauseatingly to the surface of our political discourse1 these days, it is probably worth some reflection regarding the role of multiculturalism in science. I’m therefore going to take a stab, despite being in most respects a ‘golden child’ in terms of privilege and opportunity (I am, after all, a middle-aged Caucasian male living in a wealthy country). My cards are on the table.

With all the nasty nationalism and xenophobia gurgling nauseatingly to the surface of our political discourse1 these days, it is probably worth some reflection regarding the role of multiculturalism in science. I’m therefore going to take a stab, despite being in most respects a ‘golden child’ in terms of privilege and opportunity (I am, after all, a middle-aged Caucasian male living in a wealthy country). My cards are on the table. Last year I wrote what has become a highly viewed post here at ConservationBytes.com about the

Last year I wrote what has become a highly viewed post here at ConservationBytes.com about the